Five Tests for What Is a Business Rule?

Consider the rule: A log-in must be cancelled if the user enters the wrong password more than 5 times. Business rule?

The tests for distinguishing business rules from system or IT rules are straightforward.[1] There are five basic tests. A rule must pass all five tests before it can be considered a true business rule. The first three tests are as follows.

Test 1. The rule must be practicable. This test entails the question, 'Would a worker who is duly authorized and capable know what to do or not to do when she reads it?' Consider the statement: No shirt, no service.[2] Probably passes the practicable test. Now consider this statement: Come as you are. Probably not practicable. A worker can't read it and know exactly what to do or not to do. The statement must be interpreted into some form that truly is practicable (e.g., No swimming suits.). More about practicable later.

Test 2. The rule must be about the business, not about either a system that supports the business, or a platform used to implement such a system. A rule of thumb is this: If you threw away the system — any system, even pencil and paper — would the rule still be important in running the business? Business people should be managing business things, not system things.

Test 3. The rule must be expressed in the language of the business, not in the language of either a system or a platform. A business person must be able to understand a statement or representation of a business rule without significant training or experience in IT or IT-built systems. Business people should be communicating in business terms, not system terms.

Now back to the original rule: A log-in must be cancelled if the user enters the wrong password more than 5 times. This rule satisfies tests 1 and 3, but not 2. Not a business rule.

How about this example: No cash, no order. This rule does satisfy all three tests. So, yes, business rule.

Does this clear distinction between business rules and system or platform rules ever break down? One commonly-cited example where the line might blur is with security rules. However, such rules often pertain directly to a system or the data in it. Consider this example: A person logged on to the system as a junior adjudicator may request customer data from the customer database only from the local server. This rule satisfies test 1 above — it's practicable — but not 2 and maybe not 3. So, not a business rule. Does that mean the rule is any less important to the business? No. It's a rule all right, simply not a business rule.

Consider another example: A junior adjudicator may be informed only about customers in his local district. Throw out the systems, you still need the rule. So, yes, business rule.

Two additional tests for when a rule can be considered a business rule are as follows.

Test 4. The rule must be under business jurisdiction. "Under business jurisdiction" is taken to mean that the business can enact, revise, and discontinue the business rule as it sees fit. If a rule is not under business jurisdiction in that sense, then it is not a business rule. For example, the law of gravity is obviously not a business rule. Neither are accepted rules of mathematics.

Test 5. The rule must tend to remove a degree of freedom. If some guidance is given but does not tend to remove some degree of freedom, it still might be useful, but it is not a rule per se. Such guidance is called an advice.

Consider the statement: A bank account may be held by a person of any age. Although the statement certainly gives business guidance, it does not directly:

- Place any obligation or prohibition on business conduct.

- Establish any necessity or impossibility for knowledge about business operations.

Because the statement removes no degree of freedom, it does not express a business rule. Rather, it expresses something that is a non-rule — a.k.a. an advice.

Is it important then to write the advice down (i.e., capture and manage it)? Maybe. Suppose the statement reflects the final resolution of a long-standing debate in the company about how old a person must be to hold a bank account. Some say 21, others 18, some 12, and some say there should be no age restriction at all. Finally the issue is resolved in favor of no age restriction. It's definitely worth writing that down!

Now consider this statement: An order $1,000 or less may be accepted on credit without a credit check. This statement of advice is different. It suggests a business rule that possibly hasn't been captured yet: An order over $1,000 must not be accepted on credit without a credit check. Let's assume the business needs this rule and considers it valid.

In that case, you should write the business rule down — not the advice — because only the business rule actually removes any degree of freedom. Just because the advice says an order $1,000 or less may be accepted on credit without a credit check, that does not necessarily mean an order over $1,000 must not. A statement of advice only says just what it says.

Categorization of Business Rules

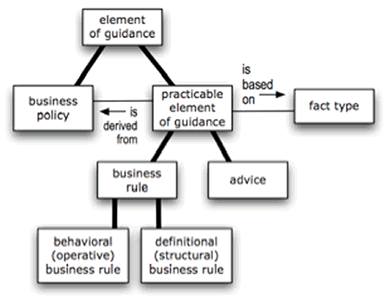

Figure 1 presents an overall categorization of guidance from the perspective of business people.[3] All rules are either behavioral (also called operative) or definitional (also called structural).[4]

Figure 1. Categorization of business guidance

More About Business Rules Being Practicable

In contrast to a business policy, a business rule needs to be practicable. This means that a person who knows about a business rule could observe a relevant situation, including his or her own behavior, and decide directly whether or not the business was complying with the business rule. In general, a business policy is not practicable in that sense; a business policy must be interpreted into some more concrete business rule(s) that satisfy its supposed intent. (That's what the fact type in Figure 1 worded practicable element of guidance is derived from business policy is about.) For example, the following business policy is not practicable: Safety is our first concern.

Just because business rules are practicable does not imply they are always automatable — many are not. For instance, consider the business rule: A hard hat must be worn in a construction site. Non-automatable rules need to be implemented within user activity. In many ways, managing non-automatable rules is even more difficult than managing automatable ones. They definitely have a place in your rulebook.

For a business rule (or an advice) to be practicable assumes that the business vocabulary on which it is based has been adequately developed, and has been made available as appropriate. Note the fact type in Figure 1 worded practicable element of guidance is based on fact type. Every business rule (and advice) should be directly based on a structured business vocabulary. Ultimately, all business rules come down to good business vocabulary!

References

[1] Portions of this article were excerpted from Business Rule Concepts: Getting to the Point of Knowledge (3rd Ed.), Chapter 7, by Ronald G. Ross, 2009. ISBN 0-941049-07-8 http://www.brsolutions.com/publications.php ![]()

[2] This sample business rule and certain others in this discussion are not well expressed. They help illustrate the five tests, not explain how best to express the rules. For guidelines about that refer to www.RuleSpeak.com. ![]()

[3] This discussion of business rules is based on, and consistent with, the OMG 2007 standard Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules (SBVR). For more about SBVR, see SBVR Insider on www.BRCommunity.com. ![]()

[4] Refer to Business Rule Concepts (3rd Ed.), Chapter 6. ![]()

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules