When the Customer Gets Lost in the Rules

Most of us have had the experience of calling customer service for one reason or another and not getting the answer we had hoped for. Sometimes we try calling back, and often we get a different answer to our question. Someone told me just the other day about calling their phone company to take advantage of a promotion the company was running, only to be told they didn't qualify. They called back, got a different representative who acknowledged the promotion and signed them right up. Just recently, I was booking a flight on one of the major airlines. It was an overseas flight and I wanted to use some upgrade coupons that I had. I was told that I couldn't because they would expire before I took my flight. Really wanting the upgrade, I held off booking the flight and placed a call to two more airline representatives until I found one that would apply the coupons to my flight. Why can't companies provide consistent service to customers?

I was asked recently how companies should handle situations where some flexibility can be applied to the rules. That's a great question because there are certain processes within an organization where flexibility is a competitive advantage and others where it's just costly. Just as Dell (and other companies like them) distinguished themselves from their competition by offering customization instead of standardization, organizations must decide if they will allow flexibility within certain areas of the customer experience.

First, an organization must decide what its strategic direction is going to be and how they are going to treat their customers. It should be a conscious choice to allow flexibility within certain parameters of the process. Once an organization has made that decision, then they must examine their processes to determine how to apply flexibility. The type of technology the organization is using and how it's configured will determine a great deal about how much flexibility is possible and reasonable to allow in a process.

Often, flexibility on the part of the staff is not possible because of the technology. Most of us have had the experience of standing across a counter or desk from the person trying to help us and they are typing just as fast as they can. Intuitively you know they're trying to work "around" the system to help you. Sometimes they're successful and sometimes they're not. The question is why do they have to work "around" the system? Why doesn't the "system" support helping the customer? Normally this is due to the fact that the "system" — and by "system" I'm referring to the technology — has been designed with such rigor that the flexibility to do something unique to help a customer is difficult, if not impossible.

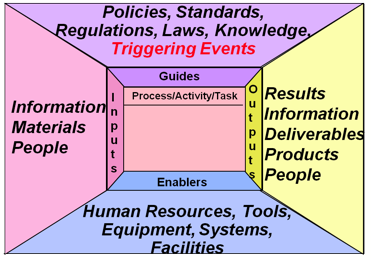

If we look at the elements of a process, it's easy to see how influential the guides and the enablers are to how flexible a process can be. Let's look at the two aspects of a process: guides and enablers. One consideration is the flexibility of the guides. The other is the flexibility of the resources that support the processes.

It is the "guides" to a process, and more specifically the rules within the guides, that drive most of the flexibility of the process. In addition, we must take into account the resources following those guides. An organization could have somewhat flexible guides/rules but the technology used to support the process is so rigorously structured that it's just not possible to really implement much flexibility. It's also possible that the guides/rules are flexible but the people resources being used to support the process don't have enough experience or authority to apply that flexibility in trying to help the customer. The interesting part of this is that if the people are extremely skilled and motivated they can overcome a lot of the constraints a system may place on a process.

Another scenario in which the customer is sometimes lost in the process can be in processes between two organizations. I was traveling to Europe last summer, when a series of circumstances delayed my initial connecting flight and then mechanical problems canceled my overseas flight. As a result I was rebooked the next day, but on another airline. I was originally booked on American Airlines, but the rebooking was on United Airlines. My ticket on American was a business class ticket, yet when I checked in for the overseas portion on United I noticed it was a coach class seat assignment, even though my printed itinerary actually showed a first class ticket.

I won't go into all the ugly details but suffice it to say that even though the mistake was made by the airlines, if I wanted it fixed I was going to have to do it myself. I had almost four hours to settle a dispute between two airlines over a mistake they made. Just fifteen minutes before boarding time, it was finally resolved. Needless to say, it was not a relaxing or fun experience for me.

It was a situation of different rules in the different airlines. Part of it was related to the fact that I had been issued a paper ticket when the flight was rebooked. United Airlines and American Airlines didn't handle paper tickets the same way, so I spent almost three and a half hours — very stressful hours — convincing these two airlines to keep the commitments they had made when the change occurred and they had both accepted the conditions of the change. As a customer, I was made to feel like I was actually inconveniencing them.

Since customers are the reason companies exist, one has to wonder how organizations have gotten to the point where it is the customer who becomes responsible for fixing their problems and is then made to feel guilty about it. In this scenario, the whole problem was caused by two things. One was the difference in rules that each airline applied to a paper ticket, and the other was the people who were part of the process. The agents at both airlines expected me to walk between the two airlines carrying various forms of paperwork to resolve the problem. Although the American Airline agents volunteered to do this for me, the United Airline agents insisted that I had to do this personally. Anyone familiar with the Chicago O'Hare airport is aware that these two airlines are not close together — in fact, they are not even in terminals next to each other. One airline is in Terminal 3 and one is in Terminal 1. I made the trip between the two terminals not once but twice.

Organizations should recognize that when their rules become so rigid that the customer is the one that suffers, something should be changed. This is a perfect example of how even the "idea" of serving the customer was completely lost. No apologies were ever offered, although American did credit my mileage account with a few thousand miles, but that wasn't even enough to buy an upgrade.

The unfortunate side of this example is that it's probably not unique. I'm sure other passengers have had similar experiences, and unfortunately some of them have probably turned out worse. It's extremely important for organizations to understand the impact that their lack of process and conflicting rules have on their customers. Given the opportunity, customers will do business with those organizations whose processes and rules are transparent because they are well known and designed based on a strategy to serve the customer. The best process an organization can have is one the customer is completely unaware of. Too often we customers not only have to understand organization's processes but, equally as important, we have to understand the rules that drive those processes.

Remember, as you look at your organization's processes, that allowing flexibility in a process should be a conscious decision. If your organization chooses to have flexible processes, you must have both the people and the systems to implement this successfully. There must be clear and consistent rules as well as some sets of parameters that allow people to offer the flexibility necessary to provide exceptional customer service to your customers.

The more complex our organizations make the rules that guide the process, the more difficult it becomes to both follow those rules and to handle exceptions to the rules. The key is consistent rules and clear processes that both staff and technology can support.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules