The Business Motivation Model: Doing the Right Things

What I can control is how I react. I can't control anything else.

~ Kelsey Grammer

Where does your BMM fit?

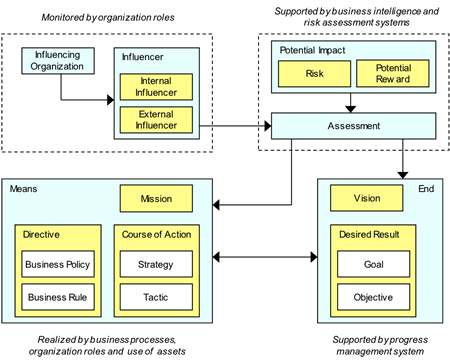

The first article in this series introduced the Business Motivation Model,[1] as illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1. Areas of Activity Covered by the BMM.

In Zachman Framework terms,[2] a BMM would sit in the Motivation ('Why') column, with

- scope, mission, and vision defined in the Executive Perspective row.

- the rest of its ends (goals and objectives) and means (strategies and tactics, governed by directives) in the Business Management Perspective row, supported by monitoring of changes in influencers and assessments of their potential impacts on the business.

The BMM provides the general vocabulary, and the business-specific vocabulary is provided by concepts defined in other cells ('What', 'How', 'Where', 'Who', and 'When') of the rows. If you don't use the Zachman Framework, then there will be (or ought to be) an equivalent position in your schema for a BMM.

A Feedback and Control System

Many BMM users get good value from their BMMs in this "top of the stack" role — a high-level model that provides the basis for developing and managing operational business and the information systems that support it.

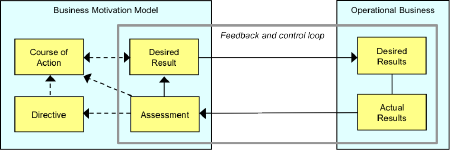

But a BMM contains a classical engineering feedback and control model, as illustrated in Figure 2, and you can get even more value from your BMM by using it.

Figure 2. Feedback and Control.

To use your BMM for feedback and control, think of it as sitting outside your operational business, monitoring and tuning it. The desired results (goals and objectives) defined in your BMM become performance targets in your operational business. Significant differences between them and actual results are handled as a kind of internal influencer, causing assessments which, perhaps, lead to changes in desired results, courses of action, and directives.

Note that this is not a different BMM. It's just a role of your BMM, focused on operational performance, in addition to its more general role as "top of the stack."

"Doing Things Right" vs. "Doing the Right Things"

"Doing things right" means that your business is undertaking your BMM's courses of action (strategies and tactics) as the stakeholders intended. Ensuring that this is so is part of your management of operational performance: process quality, employee performance, product quality, service delivery, regulatory compliance, etc. You ought to be managing this conformance at the operational level. It should be visible to the BMM only if there are persistent concerns that require strategic or tactical action by stakeholders.

"Doing the right things" means that your BMM's courses of action (strategies and tactics) are delivering the results you expected them to (or hoped they would). It doesn't matter how well you are "doing things right" if they are not the right things to do.

The problem is that you can't control very much. Some influencers are internal, and you can react to them directly by changing how your business operates. Even so, there may be unintended consequences. For example: it's hard to imagine an organization being more confident of being in control than the rule-making committee for an Olympic sport. Yet, in the 2012 Olympics, four women's badminton pairs were expelled for "unsporting conduct"[3] after deliberately losing matches. The competition rules had been changed — presumably in response to some unspecified influencer — and this change allowed pairs to play tactically in order to optimize the number of medals their country would win. (Note that in BMM terms, "unsporting conduct" is in the corporate value category of internal influencer and, like many such influencers, is implied. The expelled pairs had not broken any explicit rules.)

Mostly, you will be developing courses of action that you expect will lead to your desired results, but you won't be able to control your customers or competitors or regulators, or the market prices for your inputs, or innovation from third parties, or availability of important skills. The best you can hope for is that your courses of action will influence them in ways that are favourable to your business.

Here are three important considerations:

- Your stakeholders will not always define courses of action that deliver the desired results. This isn't necessarily because they didn't choose the best courses of action; there will be other organizations out there also trying to influence the same states of affairs, and some will succeed. You will need to ensure that your stakeholders understand (and accept) this.

- It may not be immediately apparent when courses of action are not doing the right things. Recently there was an article on independenttraveler.com[4] giving a passenger's perspective on airline fees for checked bags. Most US airlines have introduced these charges during the past couple of years, but with different charges and different rules; some have not, but may do so in the future. It will probably be some time before individual airlines can decide if their variants on this course of action are doing the right things for them. The independenttraveler.com suggests that there are unintended consequences; some airlines may be disappointed.

- When it becomes apparent that some courses of action are not doing the right things, then those courses of action need to be changed. This may seem obvious, but it's surprising how often organizations adopt courses of action that they assume will do the right things, and then focus only on "doing things right."

Feedback and Control

Selecting the metrics

The most important factor in effective feedback and control is selecting the right metrics. Identifying the right metrics can sometimes clarify what courses of action you ought to take.

For example, in the late 1990s, the UK government wanted to improve service levels in the UK National Health Service (NHS). It was being criticized by its political opposition and a large section of the popular press about the size of patient waiting lists for some categories of treatment.

But if you are a NHS patient, you don't wait for treatment in a physical line of patients who are ahead of you. You get a letter telling you when your treatment will happen. You probably don't know how many people are ahead of you — and you don't care. What is important to you is how long you will have to wait. List length and waiting time are related, but list length is not the only thing that affects waiting time. When the focus changed to waiting time, the situation — including patient satisfaction — began to improve quite quickly. In retrospect this seems obvious but, at the time, all the debate and criticism was about waiting lists. Hindsight is wonderful.

Now, NHS Choices[5] — the web "front door" for NHS patients — presents its information in terms of waiting times. When the subject is raised in the media the headlines are, still, almost always about waiting lists.

So, you need to select the right metrics. In order to do that, you need to be clear on what your desired results are. For the NHS, the goal was probably something like "acceptable level of patient satisfaction while maintaining quality of care at acceptable cost" (saying "acceptable" allows moving targets over time). One of its constituents would be "acceptable waiting times," requiring a course of action to reduce waiting times if they were not acceptable. Shortened waiting list length might (or might not) be a side effect of such a course of action, but it is not directly relevant to the goal.

Selecting the right metrics is often not easy. Airlines' charging for checked bags is, presumably, a course of action in support of some revenue improvement or revenue protection goal. How will an airline decide whether it is doing the right thing? How will it separate the effects of charging for checked bags from those of other factors that affect revenue, passenger satisfaction, gate and cabin staff stress, and departure delays?

Support from your BMM

Concepts in a BMM are defined in text. You can include anything you decide is relevant, either directly or by references to (for example) reports, statistical models, simulations, publications, and web sites. You might consider including

- an indication of how confident you are that your courses of action will do the right things. This can be part of the description of an assessment, or of individual courses of action decided on as outcomes of the assessment.

- an indication of what level of negative feedback — the difference between desired results and actual results — should cause courses of action (or desired results) being reviewed. This can be included in the description of desired results.

- options to be considered if your courses of action aren't doing the right things. A good place to start is with the rejected options described in the relevant assessment(s). An order of preference, perhaps approved by stakeholders, is often useful.

- when a course of action is replaced or removed, along with the reasons why it was determined not to be doing the right things.

As you use your BMM, it will document your experience — what didn't work as expected, as well as what did. You will also be able to create categories of influencers and assessments to help you and your stakeholders retrieve relevant experience. In the next article we shall look at categorization in more detail.

BMM scope

Part 1 of this series mentioned that a BMM does not have to represent the entire business: "From time to time you might want to create a BMM of a partial view, focused on particular concerns, such as staff retention, exploitation of a new technology or an organizational change."

Using the BMM's feedback and control loop may be particularly useful with this kind of narrowly-focused model. We shall return to this later in the series.

References

[1] Object Management Group (OMG), Business Motivation Model (BMM), at www.omg.org/spec/BMM/1.1 ![]()

[2] John A. Zachman, John Zachman's Concise Definition of The Zachman Framework™, ©2008, at zachman.com/about-the-zachman-framework ![]()

[3] "Badminton pairs expelled from London 2012 Olympics after 'match-fixing' scandal," The Telegraph, Oct. 2, 2013, at http://bit.ly/Plz1FV ![]()

[4] "Baggage Fees: The Unintended Consequences," IndependentTraveler.com, at independenttraveler.com/travel-tips/travelers-ed/baggage-fees-the-unintended-consequences ![]()

[5] "NHS waiting times — Guide to waiting times," NHS choices, at http://bit.ly/pH6BYG ![]()

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.