Decision Tables and Integrity: Introducing Restrictions

Extracted from Decision Tables: A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™, by Ronald G. Ross, 2013, available (free) on http://www.brsolutions.com/IPSpeakPrimers See [glossary definitions] for terms colored like this: decision table

Three basic reasons for diminished integrity (correctness) in decision logic are:

- Invalid decision rules.

This business problem can be resolved only by knowledge workers and business analysts working under an appropriate methodology.

- Structural deficiencies and lack of adequate support that permit anomalies to arise in decision tables.

Potential anomalies can be controlled by careful design and, if available, appropriate software.

- Lack of adequate controls over management and revision of decision tables such that their meaning (semantics) is compromised.

This third problem centers on decision table management, the focus of this discussion.

A restriction is a business rule that directly governs the integrity (correctness) of a decision table. Restrictions apply to the content of almost any decision table. Identifying, specifying, and managing restrictions are a critical part of decision table management. Failure in this regard can exact a high price.

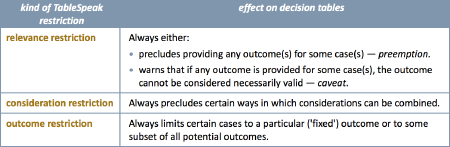

Table 1 lists the three fundamental kinds of restriction that can be placed on decision tables. Each is discussed and illustrated below.

Table 1. Kinds of Restriction in TableSpeak.

Observations

- These three kinds of restriction in TableSpeak correspond exactly to the three kinds of decision dependencies in DecisionSpeak™: relevance dependency, consideration dependency, and outcome dependency, respectively.[1] DecisionSpeak and TableSpeak fit hand-in-glove with each other.

- Between them, these three kinds of restriction cover everything pertinent to any business-oriented decision table:

- The question (via relevance restrictions).

- The consideration(s) — and through them, elemental cases and intersection cases.

- Outcomes.

Literally, there is nothing else in decision tables to restrict.

- A restriction often affects multiple cells in a decision table. Defining a restriction not only allows single-sourcing of the related business intent but also supports its faithful retention and consistent application as the decision table undergoes modifications over time.

About TableSpeak™

TableSpeak is a BRS set of conventions for business-friendly representation of decision tables and their meaning (semantics) in declarative fashion.

Central to TableSpeak are:

- Highly pragmatic guidelines and thresholds for selecting the best decision-table format. TableSpeak avoids simplistic and counterproductive one-size-fits-all approaches.

- The principle of single-sourcing, essential for achieving true business agility.

- Restrictions — business rules for ensuring the integrity (correctness) of decision-table content.

TableSpeak optimizes for readability by non-IT professionals and business people.

Decision tables based on TableSpeak are free of hidden assumptions and implicit interpretation semantics.

- The question the decision table answers is always emphasized.

- Scope (applicability) is declared explicitly.

- Unnecessary complications to decision-table structure (such as exceptions) are externalized.

- Meaning is comprehensively expressed.

- Business vocabulary is carefully used.

Relevance Restrictions

A relevance restriction always answers the following general pattern question:

Can an outcome from one significant operational business decision make any outcome from a second operational business decision meaningless?

As applied to a decision table a relevance restriction always either

- precludes any outcome(s) for some case(s) from the second decision.

(In this role the relevance restriction produces a preemption.)

- warns that if any outcome is provided for certain case(s) from the second decision, the outcome is not necessarily valid.

(In this role the relevance restriction produces a caveat.)

These roles are individually discussed and illustrated below.

Relevance Restrictions as Preemptions

DecisionSpeak recognizes relevance dependencies between operational business decisions. A relevance dependency occurs when the answer to one question can completely eliminate the need or possibility for an answer to another question. In such cases the other operational business decision is preempted — made meaningless.

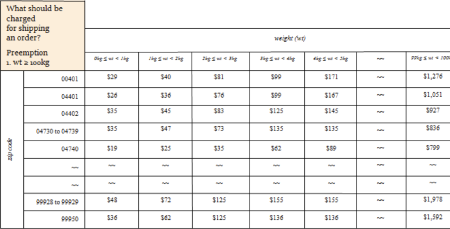

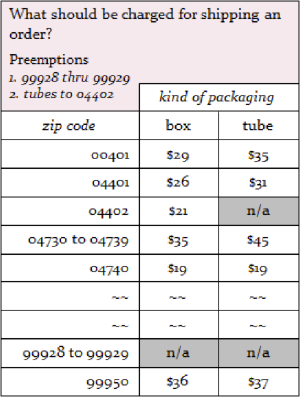

For example, suppose the business with the operational business decision What should be charged for shipping an order? in Figure 1 decides not to ship

- any orders to certain zip codes. Possibly those cases are unprofitable, too slow, too dangerous, or too difficult to manage.

- tubes to certain zip codes. Possibly the postal facilities in those cases do not have the right kind of equipment.

For these particular cases:

- Asking the question What should be charged for shipping an order? is pointless because the answer to the more basic business question Can an order be shipped to a customer? is no.

- There is no shipping charge whatsoever (at least not one that's usable). Any shipping charge has been made meaningless — preempted.

Figure 1 shows the appropriate specifications for these restrictions.

Figure 1. Restriction for Preempted Cases by Zip Code and Kind of Packaging

The decision cell(s) for all preempted cases in the decision table have been

- grayed-out. Gray-out is a TableSpeak convention indicating no revision (updating) is permitted (at least until the restriction is lifted, if ever).

- specified as n/a (not applicable). Such a case is preempted; that is, no outcome for it is meaningful.

The advantage of retaining grayed-out decision cells with n/a in the decision table is to emphasize that the cases have not been overlooked. Omitting the cases from the decision table could be mistaken for omissions (missing rules), which they are not.

Observations

- Although the first restriction above affects multiple cells (two), its specification has been single-sourced.

If some change(s) to the preemptions and/or to any of the affected outcome(s) are subsequently desired, the restrictions provide a single point to coordinate (permit) change to the outcome(s).

- Preemptions can be much more complex than those illustrated above. For example, they might require specifying separate lists or tables.

As an additional example, suppose the business with the operational business decision What should be charged for shipping an order? in Figure 2 decides not to ship orders that weigh 100 kgs or more. For these cases,

- asking the question What should be charged for shipping an order? is pointless because the answer to the more basic business question Can an order be shipped to a customer? is no.

- there is no shipping charge whatsoever (at least not one you can use). Any shipping charge has intentionally been made meaningless — preempted.

Figure 2 shows the appropriate specifications for this restriction.

Figure 2. Restriction for Preempted Cases by Weight.

The decision cell(s) for preempted cases in this decision table (weight ≥ 100kgs) have not been shown. They don't have to be — that's an option. If someone tried to update the decision table to show such a case, however, the restriction would have to be removed first. The original business intent has been retained and is being continuously enforced by the restriction.

Relevance Restrictions as Caveats

A relevance restriction that acts as a caveat is really just a weaker version of a preemption. The decision logic basically says: "Here's an outcome, but don't count on it being valid because the business question hasn't been asked properly."

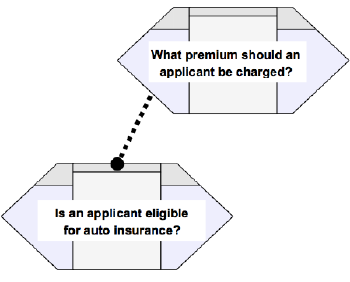

Consider the following example of relevance dependency between two operational business decisions.

In determining eligibility of applicants for auto insurance, if an applicant is not eligible for coverage, there is no need to determine what to charge the applicant as a premium. This relevance dependency is illustrated in Figure 3 using a Q-Chart.[2]

Figure 3. Q-Chart Showing a Relevance Dependency Between Operational Business Decisions

Must processes always address the questions involved in a relevance dependency in bottom-to-top sequence? No.

For the questions in Figure 3, for example, a customer-friendly, web-based application might permit price-conscious consumers to ask about the premium before asking about eligibility. Some precautions, however, should clearly be taken. Any outcome produced in a price-before-eligibility sequence is not necessarily valid.

The solution is to specify a restriction that requires a caveat to be issued along with the premium. The caveat, in the form of a message, is specified as part of the restriction. The message for the example above might be worded:

Securing coverage at the given price subject to eligibility.

The restriction ensures a disclaimer is given by any process or use case that supports a price-before-eligibility sequence.

Consideration Restrictions

A consideration restriction always answers the following general pattern question:

Are there ways in which considerations should not be combined?

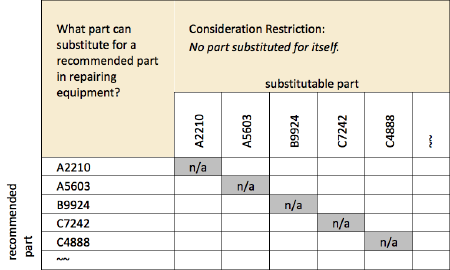

A consideration restriction always constrains combination of elemental cases into intersection cases within a decision table. The net effect is to prohibit certain intersection cases that would otherwise be possible. Examples are provided in Figures 4 (only partially populated) and 5.

A part naturally cannot be substituted for itself. Such combinations (intersection cells) are meaningless given the question the decision table addresses.

In Figure 4 a consideration restriction has been specified (at top) to preclude such possibility.

Figure 4. Example of a Consideration Restriction Prohibiting Combinations of Self with Self

Observations

- Although the restriction affects multiple cells, its specification has been single-sourced.

- Gray-out of the intersection cells indicates no revision (updating) is permitted (at least until the restriction is lifted, if ever).

Figure 5. Example of Elemental Case for One Consideration Precluding Any Elemental Case for Another Consideration

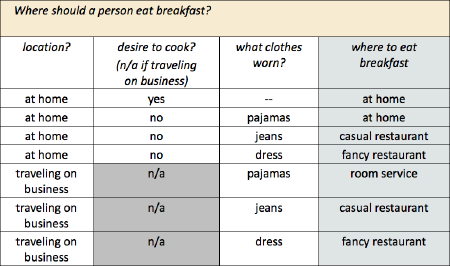

For the example illustrated by Figure 5, let's assume that traveling on business (for the location? consideration) precludes desire to cook? (the consideration in the second column). The consideration restriction, n/a if traveling on business, has consequently been specified for the desire to cook? consideration.

The intersection cases given by the bottom three rows are thereby constrained — combinations including yes and no for the desire to cook? consideration are not permitted.

- Yes obviously needs to be disallowed because when traveling on business there is usually nowhere to cook.

- No is also disallowed because not desiring to cook is different than not being able to cook — it's not the same meaning.

Gray-out of intersection cells in Figure 5 indicates no revision (updating) is permitted for them (at least until the restriction is lifted, if ever).

Outcome Restrictions

An outcome restriction always answers the following general pattern question:

Are certain cases limited to a particular outcome or to some subset of all potential outcomes?

An outcome restriction applied to a decision table directly constrains outcomes. The net effect of an outcome restriction is always either to

- establish a 'fixed' (or 'set') outcome for some case(s).

or

- narrow the set of potential outcomes for some case(s).

Use of outcome restrictions for each of these roles is discussed and illustrated individually below.

Fixing the Outcome for Some Case(s)

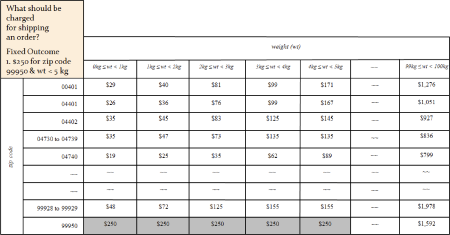

To illustrate a fixed outcome, let's return to the operational business decision What should be charged for shipping an order? examined earlier. Suppose the business wants to set a fixed price, $250, to ship orders that weigh less than 5 kgs to zip code 99950. Figure 6 illustrates how the fixed price can be specified as an outcome restriction.

Figure 6. Specifying a Fixed Outcome.

Observations

- In Figure 6 the outcome restriction $250 for zip code 99950 & weight < 5 kg has been specified. All corresponding intersection cases in the decision table show the outcome $250.

- The outcome restriction affects multiple cells (five). Defining the restriction only once allows single-sourcing of business intent.

- Since the outcome restriction prohibits any of these outcomes from being changed, these intersection cells are grayed-out. Otherwise, direct assertions of prices differing from $250 could easily occur.

Narrow the Set of Possible Outcomes for Some Case(s)

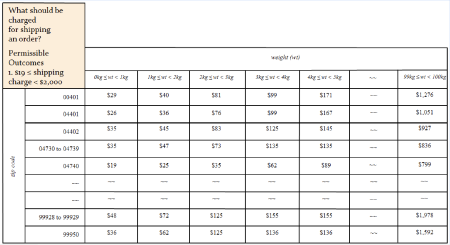

Rather than fixing outcomes, an outcome restriction can also be used to narrow the set of permissible outcomes for some or all cases. Figures 7, 8, and 9 illustrate.

In Figure 7 the outcome restriction $19 ≤ shipping charge < $2,000 is specified. All intersection cases in the decision table consequently must fall into this range. No modification (updating) of the table is allowed that would violate this restriction.

Figure 7. Range of Permissible Outcomes.

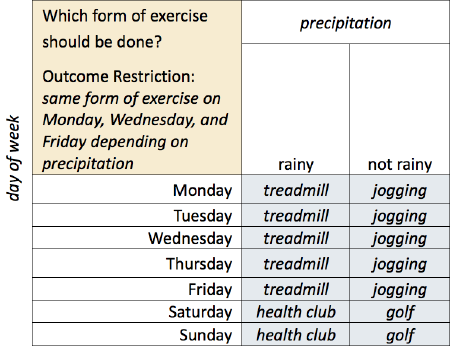

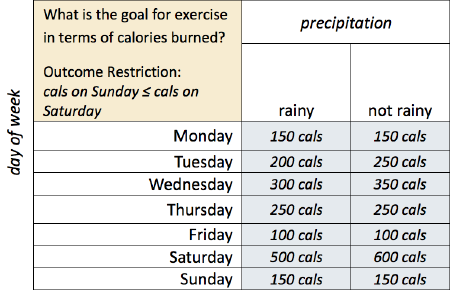

In Figure 8 the outcome restriction same form of exercise on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday depending on precipitation is specified. No modification (updating) of the decision table is allowed that would violate this restriction.

Figure 8. Inter-Outcome Consistency

In Figure 9 the outcome restriction cals on Sunday ≤ cals on Saturday is specified. No modification (updating) of the decision table is allowed that would violate this restriction.

Figure 9. Inter-Outcome Dependency

For further information, please visit BRSolutions.com

References

[1] Decision Analysis: A Primer — How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™): http://www.brsolutions.com/IPSpeakPrimers ![]()

[2] from Decision Analysis: A Primer — How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™): http://www.brsolutions.com/IPSpeakPrimers ![]()

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules