Business Rules Hierarchy: The World of Business Rules Is Not Flat

This article was written in response to an invitation from the Executive Editor of the Business Rules Journal (www.brcommunity.com). It is based on part of a case study [1] presented at the 2015 Building Business Capability conference, which illustrated and discussed a hierarchical organization of business rules to support operations of immunization information systems (IIS) [2].

Hierarchical organization of business rule models can help business analysts manage the complexity and chaos common in business operations and processes. This article discusses our experience with implementing hierarchical business rule models in the public health domain of immunization information systems. We interpret laws and regulations into principles (high-level business rules) that capture strategies and desired business policies, and elucidate those principles into detailed business rules. Such an approach results in a logical organization of analysis models that is beneficial for many aspects of conducting analysis with business rule techniques.

Hierarchical Organization: A Way to Deal with Complexity and Chaos

The main task of business analysis is to make sense of the vast amount of information about a business. Quite commonly, this information is conflicting and, therefore, difficult to interpret correctly. A position description for a Senior Business Analyst at a major software company demonstrates associated challenges and reflects common expectations that the candidate will "… demonstrate the ability and inclination to tolerate chaos, ambiguity, and lack of knowledge, and to function effectively in spite of them."[2] How can business analysis techniques, especially business rules, be of help to manage the complexity and chaos mentioned in that job ad?

Separation of a decision-making logic from a description of the operation workflow is a key methodological principle of business analysis. It reflects a fundamental engineering approach to complexity: partition a complex system or task and deal with each part separately. Specifically, during business analysis with business rules techniques, a business analyst presents the decision-making logic, separated from the process steps, as a collection of business rules. As a result, complexity is removed from a process model and placed in business rules — the analysis instrument that is much better at handling decision-making intricacies. Partitioning also results in simplified or streamlined (i.e., "thin/lean") process models that are easier to implement and maintain.

Hierarchical organization of a business analysis model represents a different form of partitioning that addresses complexity by developing models of the same type, but with a different level of detail. It reflects another fundamental analysis principle — from generic to specific — that is broadly used in many areas (e.g., in deductive reasoning). High-level and detailed process models, as well as conceptual and logical data models, are examples of such a hierarchical organization. A similar approach can be implemented for business rule models. Hierarchical organization of business rule models, with high-level (more general) business rules at the top level and detailed (more specific) business rules at the lower level, is one of the approaches to address the complexity and chaos that a business analyst commonly faces.

Hierarchical Organization: A Way to Accurately Represent Institutional Knowledge

Business rules represent institutional knowledge about the operations of a business. A typical institutional knowledge base is complex and includes both generic and specific components. Simply speaking, the world of operational knowledge is not flat. In the same way as any other model, a business rule model needs to reflect this reality.

Governing Rules and Practicable Rules

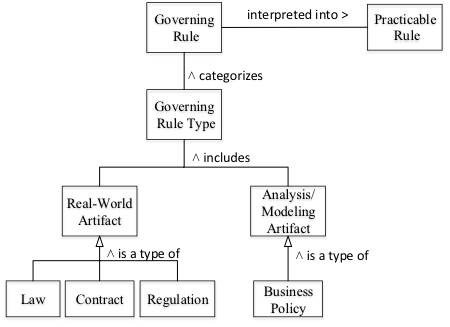

Landmark works on business rules by R. Ross [3, 4] describe two kinds of rule-related artifacts: "governing rules" (laws, acts, statutes, regulations, contracts, business policies, legal determinations, etc.) and "practicable rules" (more concrete business rules, often interpreted from governing rules). This relationship between governing rules and practicable rules points to two distinct association types (Figure 1):

- Between real world artifacts, such as laws, contracts, regulations, etc., and elements of a model, (i.e., business rules).

- Between different elements of a model (e.g., between business policies and individual business rules).

Figure 1. Governing Rules and Practicable Rules.

More often than not, practitioners rely on the first type of association — interpreting laws, regulations, and contracts into practicable business rules. This article focuses on the second type of association — that within the business model (i.e., relationships between business policies that we refer to as "high-level business rules or principles" and detailed business rules).

Hierarchical Organization of Business Rule Models

From the organizational perspective, we usually partition a business rule model on two hierarchical levels — principles (high level) and business rules (low level). This allows us to organize a business rule model logically from more generic to more specific components.

- A principle (high-level component) can be thought of as a guiding component of operational knowledge, a high-level business rule. It provides a direction that helps to guide development of the more specific business rules.

- Business rules (low-level components) represent specific guidance and decision-making logic for various aspects of business operations and processes.

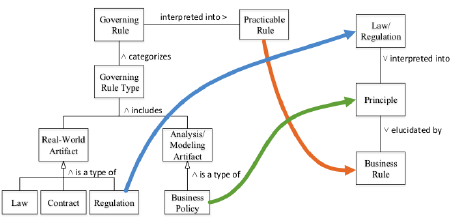

We view principles as elements of a business rule model that provide a link between real-world guidance, such as laws and regulations, and detailed elements of a business rule model, such as business rules. This approach allows us to interpret laws and regulations into principles that capture desired business policies, and then elucidate those principles into business rules (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hierarchical Organization of a Business Rule Model

It is a two-step process versus a one-step process of interpreting governing rules directly into practicable rules. As a result, both principles and business rules interpret laws and regulations, but with a different degree of specificity. Such a hierarchical organization provides for a more natural and explicit traceability from governing rules to fundamental operational principles to more specific, practicable business rules.

Examples from the public health domain of immunization information systems (IIS) illustrate progressive elucidation of real-world regulations into elements of a business rule model — principles and detailed business rules associated with these principles.

The first example is from the reminder/recall area of IIS operations. Reminders are notifications sent to patients who are due for scheduled immunizations. Recalls are notifications sent to patients who are past due for immunizations.

- An authoritative regulation for the reminder/recall functional area is formulated in the IIS Functional Standards [5]: The IIS should automatically identify individuals due/past due for immunization(s), to enable the production of reminder/recall notifications.

- Principles develop this regulation to operational guidance in a direction that reflects a common limitation of resources [6]:

- Limited resources principle: Reminder/recall activities must be in line with available resources. Accordingly, not every recommended vaccination should result in a reminder/recall notification.

- Supremacy of recall over reminder principle: When resources are limited, recalls are more important than reminders.

- Priority for children 0–24 months of age principle: Priority should be given to recalls for children 0–24 months of age.

- Business rules develop these principles further, providing specific operational decision-making logic [6]:

- Business Rule 1: When resources allow for only one recall for children 0–24 months of age, it should be at 19-21 months of age.

- Business Rule 2: When resources allow for only two recalls for children 0–24 months of age, they should be first at 7 months of age and then at 19–21 months of age.

- Business Rule 3: When resources allow for only three recalls for children 0–24 months of age, they should be first at 3 months of age, then at 7 months of age, and then at 19–21 months of age.

This example demonstrates how a business analyst can hierarchically organize operational considerations in limited-resource situations into a business rule model for managing the chaos resulting from a multitude of considerations. The IIS functional standard provides a general direction. Principles that acknowledge common limitation of resources give priority to recalls over reminders and channel resources to a cohort of children 0–24 months of age. Business rules associated with these principles specify that guidance in greater detail.

Another example is from the inventory management area of IIS operations:

- IIS Functional Standards [5] formulate an authoritative regulation for the inventory management area: The IIS should have a vaccine inventory functionality to track and decrement inventory at the immunization provider's site level.

- A principle develops this regulation to high-level operational guidance:

- Completeness principle [7]: Information submitted by an immunization provider to an IIS must contain the minimum/mandatory set of data items sufficient to support inventory management functionality.

- A business rule elucidates this principle, providing specific operational decision-making logic [7]: For every vaccine dose, the minimum/mandatory set of data items recorded and reported to the IIS for inventory management purposes should include:

- Lot number

- Lot number expiration date

- Patient eligibility status for immunization programs

- Public/private inventory indicator

- Provider organization responsible for the inventory

Once again, in this example, a general authoritative regulation is developed further by a principle, which is elucidated by a detailed business rule into specific operational guidance.

It should be noted that principles do not always originate from laws and regulations and cannot always be linked to them. Nevertheless, in such cases, the hierarchy of a business rule model would include the same two levels: principles (high level) and detailed business rules (low level).

Discussion: Practical Considerations

Our practice, going back to 2005 [8, 9], indicates that a hierarchical organization of business rule models is beneficial for many aspects of conducting analysis with business rule techniques:

- It is quite natural to organize operational knowledge hierarchically so that business rules are grouped around principles that interpret business regulations. The resulting business rule model becomes more manageable for business analysts and easier to review and reference for subject matter experts.

- Updates are easier to compartmentalize and implement, especially since principles usually have a slower cycle of change than do detailed business rules.

- Business rule models can be better harmonized with other types of analysis models. For example, principles can be associated with phases of high-level process models and business rules, with steps of detailed process models.

- Presentations of a hierarchical business rule model can be tailored for a particular audience. For example, policymakers can focus on high-level principles, and those involved in operations can focus on low-level detailed business rules.

From the implementation perspective, hierarchical organization of a business rule model can be easily supported by simple analysis tools such as Microsoft Word® and Microsoft Excel®.[3] Commercial software packages for specialized business rule modeling should be able to provide more sophisticated support for a business rule hierarchy.

In conclusion, as a practical tip, our opinion is that principles (high-level business rules) should be treated as the most important part of a business rule model. According to Claude Helvetius, "Knowledge of some principles easily compensates the lack of knowledge of many facts." When resources are limited (which is almost always the case), ensuring principles (i.e., high-level directions) are correct is more important than perfecting other components of a business rule model such as a supporting vocabulary and facts model.

Implementation of hierarchically-organized business rule models to capture operational best practice recommendations in IIS public health settings resulted in a positive outcome. The recommendations we developed [9, 10] are successfully used by many immunization information systems in the United States [11]. We believe that application of such an approach can be beneficial in other settings as well.

May the hierarchically organized force be with you!

Notes[1] DISCLAIMER: The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ![]()

[2] This quotation was contributed by Steve Farrell, Advanced Strategies, Inc. ![]()

[3] This does not constitute an endorsement of these products by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ![]()

References

[1] Williams W, Lyalin D, Myerburg S, Larson E. Leveraging Business Rules Techniques for Public Health Projects. Presentation at the 2015 Building Business Capability Conference; November 5, 2015; Las Vegas, NV. URL:

http://www.buildingbusinesscapability.com/agenda/2015_details/2193/

[2] Immunization Information Systems, URL:

http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/about.html

[3] Ross, Ronald G. Business Rule Concepts. Third Edition. Business Rule Solutions, LLC, 2009, 158 p.

[4] Ross, Ronald G. Principles of the Business Rule Approach. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2003, 372 p.

[5] 2013-2017 Immunization Information System (IIS) Functional Standards, URL:

http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/func-stds.html

[6] AIRA Modeling of Immunization Registry Operations Work Group (eds). Reminder/Recall in Immunization Information Systems. Atlanta, GA: American Immunization Registry Association. April 2009, URL:

http://www.immregistries.org/resources/AIRA-MIROW_RR_041009.pdf

[7] AIRA Modeling of Immunization Registry Operations Work Group (eds). Immunization Information System Inventory Management Operations. Atlanta, GA: American Immunization Registry Association. June 2012. URL:

http://www.immregistries.org/AIRA-MIROW-Inventory-Management-best-practice-guide-06-14-2012.pdf

[8] AIRA Modeling of Immunization Registry Operations Work Group (eds). Vaccination level deduplication in Immunization Information Systems. Atlanta, GA: American Immunization Registry Association. December 2006. URL:

http://www.immregistries.org/resources/AIRA-BP_guide_Vaccine_DeDup_120706.pdf

[9] Williams W, Lowery E, Lyalin D, Lambrecht N, Riddick S, Sutliff C, Papadouka V. Development and Utilization of Best Practice Operational Guidelines for Immunization Information Systems. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice. 2011; 17(5): 449-456.

[10] Modeling of Immunization Registry Operations Workgroup. URL:

http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/programs/iis/activities/mirow.html

[11] Dombkowski K, Cowan A, Clark S. Immunization Registry Operational Guidelines Evaluation. Final Report. University of Michigan, July, 2014. URL:

http://www.aira.browsermedia.com/AIRA_MIROW_Evaluation_Final_Report_2014.pdf

# # #

About our Contributor(s):

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.