The Need for Smart Enough Systems (Part 1)

The Importance of Operational Decisions

Smart enough systems deliver effective automation of the decisions that drive organizations' day-to-day operations. Although organizations have automated standard processes with enterprise software, these operational decisions haven't been the focus of investment. [See Sidebar] They are overwhelmingly made manually or automated poorly, which is a mistake. Embedding business processes in systems to streamline operations but not managing and improving these decisions leaves half the opportunities for improvement untouched. The means and the resources are now available to close that gap.

For more than a decade, organizations have strived to make their operations more efficient by rationalizing business processes, eliminating the handoffs between people that added latency and cost, driving down the cost of support with software standardization and data center consolidation, and outsourcing. None of these efforts, even the most successful ones, provided much more than a short-term competitive advantage, because they attacked the problem from the denominator -- revenue per employee, sales per store -- always focused on taking out cost but not emphasizing the numerator: benefits. Unfortunately, this approach is what's known as a "Red Queen" exercise, a reference to the Red Queen observing to Alice in Wonderland, "In this place, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place."

For many organizations, the only way information technology has been applied to decisions is in the form of business intelligence or decision support -- analyzing of data to help someone make a decision. Decision support as a discipline has always been aimed at the small segment of the population that uses data to make important decisions in organizations: managers and knowledge workers. It hasn't been effective at more fine-tuned, operational decision making that's just as crucial to the organization's well-being, if not more so. In addition, current enterprise data architectures are cleanly divided between operational systems and those that support the analytical and reporting processes behind decision support. This division leads to excessive duplication of data, latency in its accessibility, and usually a high degree of mismatch between analytical and operational data. Coupled with the rapidly increasing volumes of data being generated and the increasing rate of disparity as data arrives from external sources, the situation needs a better solution.

What's needed is a blueprint for orienting data, systems, and people to manage operational decisions more effectively and a way to automate decisions when appropriate and streamline those that still require some level of human intervention. Smart enough systems are computer applications that have enough intelligence to make these kinds of decisions without intervention. These systems offer a true strategic advantage. To understand why, you need to consider what "strategic" advantages involve, as discussed in the next section.

Strategy Drives Decision making

"The essence of strategy is choosing to perform activities differently than rivals do."

~ Dr. Michael Porter, Bishop William Lawrence University Professor at Harvard Business School

Dr. Porter's quote is more relevant today than ever. With fewer geographic barriers and always-on connectivity, your organization must behave differently to stand out from the crowd. You might choose to perform activities that your competitors don't perform, not perform activities your competitors do, or (most likely) perform the same activities but perform them differently.

Critical to behaving differently is an ability to decide differently. Deciding when to omit or add an activity and when and how to change the way you perform an activity are essential. A strategic advantage must make an impact on strategy, which means it must change your decisions.

The decisions you must change could be occasional strategic decisions, such as whether to acquire a certain company or enter a new market. Or they could be more tactical and operational, focused on how you treat a customer the next time he calls your call center or how you price a product on your Web site. All these decisions must be driven by your strategy if you are to deliver effectively on that strategy. Although your organization probably focuses on getting major strategic decisions correct, you might struggle to keep your operational activities -- the way front-line members of staff and applications behave -- synchronized with your strategic plans. For example:

- You might want to treat all gold customers a certain way, but you have a self-

service application that doesn't differentiate between customers.

- You might want to get more aggressive about retaining customers who are likely to leave, but your call center representatives have too many campaigns to remember, so they treat everyone the same.

- You might want to offer dynamic pricing to suppliers, but the software that drives your Web site does not use the pricing algorithms sales representatives use.

Unless your operational activities reflect your strategy accurately, your organization can't succeed. You can't even be said to be implementing your strategy.

Strategy Is Not Static

The problem of ensuring that your operational activities match your strategy is exacerbated by the need for business agility. Business agility is critical to survival in a rapidly changing world, so your strategy can't be static. You must constantly refine and update it to keep up with competitors, market shifts, and consumer preferences.

Most executives say their companies are facing a more competitive environment than they were five years ago; in fact, 85 percent say "more" or "much more."[1] Organizations that want to compete effectively must change continuously and base those changes on feedback about what is and isn't working. Those unwilling or unable to do so must recognize that they will soon be competing with organizations that have changed, if they aren't doing so already. No organization can remain immune; all will have to change somehow.

Not only must your strategy change more rapidly, but you also have more information about why and how it must change than ever before. The growth in business intelligence and performance management systems[2] means you have more insight into how well (or poorly) you are doing. To respond effectively to this new understanding, however, delivering new processes, skills, and expertise rapidly to front-line workers and information systems is essential.

For instance, if your analysis of last week's sales shows that a competitor is eating into your sales, and you decide a new pricing model is required, many factors influence how quickly you can respond. Your cultural willingness to change, for example, or your escalation and sign-off processes determine how quickly you go from recognizing a problem to intending to respond to it. The key issue, however, is likely to be how quickly you can move from that intent to a change in the operational behavior that implements your new strategy. After all, if your operations haven't changed, no customer or other associate is likely to notice -- they won't detect the change in your pricing or how it affects them.

However, changing your operations means changing the way your operational information systems behave. Your information systems characterize your operations in such a fundamental way that you can no longer separate them from your business -- your systems are your business. The time it takes to change your operational systems determines how fast you can modify your operations and is the ultimate determinant of your business agility.

Agility also contributes to strategic alignment -- how well your strategies are reflected in your business operations. Without agility, your organization can't consistently carry out a new strategy without an extended period of change. Indeed, you risk never achieving strategic alignment if changes to the strategy occur faster than the organization can respond.

Often this alignment, or lack of it, can be seen in the organization's operational or front-line activities. Indeed, divergent agendas and miscommunication between those working on an organization's strategy and those carrying it out operationally are chronic problems. These disconnects can hinder executive leadership's access to information about what's really going on and their ability to effect change in organizational behavior when they see the need. A recent study[3] included the following statement:

"Most devastating, 95 percent of employees in most organizations do not understand their

[organization's] strategy."

Many things contribute to these disconnects between strategy and operations. Among them are a lack of agility (the strategy has changed too often for the employees to keep track), execution problems (the decisions made by front-line employees aren't affected by the strategy), and secrecy (the strategy is confidential, proprietary, and a competitive advantage, so fear that it will "get out" prevents its dissemination). You must solve these problems to ensure that your strategy is carried out continuously and effectively, top to bottom, by both people and information systems.

Therefore, a dynamic, agile strategy means being able to decide to act differently and then being able to apply that decision to the way your operations work. However, to change the way your operations work, you have to change the way you make operational decisions.

Operational Decisions Matter

"Most discussions of decision making assume that only senior executives make decisions or that only senior executives' decisions matter. This is a dangerous mistake."[4]

~ Peter Drucker

When most organizations think about the decisions that matter, they think about the decisions executives or boards make: the major strategic decisions that can make or break an organization. However, Peter Drucker noted that the decisions front-line workers make matter. They interact directly with your customers, partners, suppliers, and other associates but are often among the lowest-paid staff you have. They probably also have the highest turnover and are among the most likely to work for a third party or on a contract basis, yet they make crucial decisions about how your organization treats associates every day.

However, at least you actually have someone interacting with your customers or other associates when front-line workers are making decisions. Sometimes no one is involved when your computer systems interact directly with your associates. The options your interactive voice response (IVR) system lists, the way your Web site promotes products, the letter your campaign management system decides to send, the price your online booking system calculates for a customer -- these operational decisions also influence your associates.

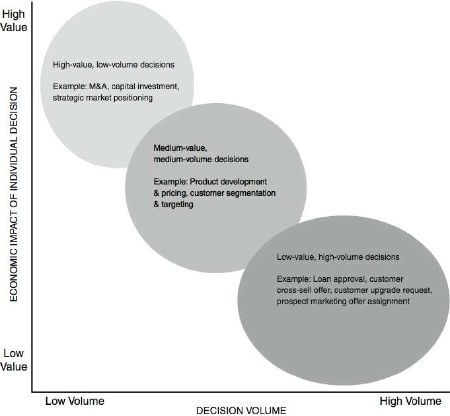

Although the influence of each operational decision is small, their cumulative effect can be huge. As shown in Figure 1, the value of individual strategic decisions is much higher than that of individual operational decisions. However, the cumulative value shows a more balanced picture. The large volumes involved in operational decisions mean that their cumulative impact can meet or exceed that of strategic decisions.

Figure 1. The value and volume of different kinds of decisions

Although a single big strategic decision has a high value, it's likely to be made with planning and analysis, thoughtfully and by the best minds in your organization. In contrast, operational decisions often aren't made so deliberately. This lack of focus is the result of several factors:

- Each decision has a low individual value; it doesn't seem that important to get the cross-sell offer for this customer just right, for example.

- The sheer volume of decisions involved is high -- hundreds, thousands, and even millions for larger organizations.

- The number of workers who handle operational decisions makes managing these decisions seem impossible.

- The time available to make most operational decisions is short, not lending itself to time spent in analysis.

- The "right" way to make these decisions changes constantly, so investing in the current approach can seem ill advised.

- Many of these decisions have been effectively delegated to the IT department by embedding them in the code of an existing system, making the decision logic hard to find or change.

Your organization will perform at its best if these high-volume operational decisions can be made at a lower cost, in real time, and with maximum consistency. The systems front-line workers use aren't smart enough to make decisions, however -- certainly not good ones. These workers also need technology to help them discover, assess, and address new opportunities and threats as they present themselves. The first person in a position to notice a customer who's unhappy or seems interested in a new product or service is likely to be a front-line worker, not someone in an office looking at a report.

What front-line workers need is better decisions. They need to be able to make decisions in high volume and narrow time windows. If they can't make or execute decisions, they can't deliver good service or effective support. If the decisions are wrong or even suboptimal, your organization will suffer. Operational decisions are critical, and making them poorly undermines productivity, prevents customer-centricity, and lowers revenue. Poor decision making reduces your organization's overall ability to be successful.

Likewise, your associates assume that the way your systems treat them is the way you want them to be treated. If the Web site, ATM, or IVR system is ineffective, that reflects badly on you. If the systems can't do what customers want, customers will call and speak to representatives, creating wait times that delay other customers.

The operational decisions at the front-line of your organization are, cumulatively, essential to your ability to run your organization the way you intend. Unless these decisions, too, are driven by your strategy and carried out with maximum effectiveness and efficiency, your organization won't perform at its best. Making good operational decisions, however, is getting harder.

Operational Decisions Are Under Pressure

Napoleon Bonaparte said, "Nothing is more difficult, and therefore more precious, than to be able to decide." Making the right operational decision is only getting harder as pressures on the decisions you must make grow:

- Decisions that once might have taken days now have to be made at the speed of the transaction, such as while your customer is completing an online purchase.

- Business objectives used to be simpler and set at the local level. Now those objectives are often set at the corporate level and involve trade-offs between risk, resource constraints, opportunity costs, and other factors.

- You're being forced to comply with more new regulations, stricter and more complex rules, shorter deadlines, and more serious consequences for noncompliance.

- You need to change your strategy -- such as how to manage customers to retain them in the face of competition -- more frequently and more rapidly to deal with competitive forces, environmental changes, and changes in your customer base.

- Decisions once owned by a single group might now be shared by multiple departments and have to be coordinated across channels and regions.

- Some decisions that were handled with manual review processes now occur in volumes or time frames that make manual processes impractical.

- The value of a decision could once be measured in terms of the cost and time needed to make it; now other objectives are also used to measure value.

Implementing your strategy means making decisions that support it every day and at all levels. It means making these decisions quickly and keeping them aligned with a strategy that adapts and changes. It means turning operational decision making into an asset, not a liability.

Operational Decision making as a Corporate Asset

If operational decisions must be made well for your organization to deliver on its strategy, they can't be made randomly. They have to be made systematically. You have to turn operational decision making into a corporate asset you can measure, control, and improve. After all, when associates interact with you, they consider every decision you make to be a "corporate" one -- that is, a deliberate one.

Every day you must make decisions faster and across more channels and product lines, which makes it harder to ensure that the decisions your organization makes are the best ones and the ones you intended to make. What makes an operational decision the right one?

Characteristics of Operational Decisions

To be effective, an operational decision must be precise, agile, consistent, fast, and cost- effective:

- Precise. Good operational decisions use data quickly and effectively to take the right action, behaving like a knowledgeable employee with the right reports and analyses. They use this data to derive insight into the future, not just awareness of the past, and use this insight to act more appropriately. They use information about customers to target them through microsegmentation and extreme personalization. They use behavioral predictions for each transaction or customer to ensure that risk and return are balanced properly, and they use the information a customer (or supplier or partner) has provided (explicitly or implicitly) to improve the customer experience.

- Agile. Operational decisions can be changed rapidly to reflect new opportunities, new organizations, and new threats; otherwise, they rapidly decline in value. No modern business system can stay static for long. The competitive, economic, and regulatory environment simply doesn't allow it. When organizations automate their processes and transactions, they often find that the time to respond to change is affected largely by how quickly they can change their information systems. To minimize lost opportunity costs and maximize overall business agility, operational decisions must be easy to change quickly and effectively. The agility of these decisions -- both the speed of identifying opportunities to improve and the readiness with which they can be changed -- ensures that they remain aligned with an organization's strategy, even as that strategy changes and evolves.

- Consistent. Your operational decisions must be consistent across the increasing range of channels you operate through -- the Web, mobile devices, interactive voice response systems, and kiosks, for example -- and across time and geography. They allow you to act differently when you choose to -- to offer a lower price online to encourage the use of a lower-cost channel, for example -- but ensure that you don't do so accidentally. These systems support third parties and agents who act on your behalf and the people who work for you directly. They enforce your organization's laws, policies, and social preferences wherever it does business and make sure you avoid fines and legal issues. They deliver a consistently excellent experience for your associates.

- Fast. You need to take the best action that time allows. The saying on the Internet is that your competition is three clicks away. Your associates are learning to be impatient and have short attention spans. Meanwhile, your supply and demand chains are becoming more real-time, and the systems that manage them must respond quickly as well as smartly. With fewer employees handling more customers, partners, and suppliers, you must eliminate the wait time for these associates. You must decide, and act, quickly.

- Cost-effective. Above all, operational decisions must be cost-effective. Despite the massive efficiency gains and cost reductions of recent years, reducing costs continues to be essential. Good operational decisions help eliminate wasteful activities and costly reports. They reduce fraud and prevent fines. They help your people be more productive and spend their time where it really matters. They make sure you do as many things right the first time as possible and avoid expensive "do-overs." They reduce the friction that slows processes and increases costs.

Operational decisions are what make your business strategy real and ensure that your organization runs effectively, right down to the front-lines interacting with your associates. To ensure that operational decisions are effective, you need to manage operational decision making. The change in mind-set required is akin to the changing view of data over the past few years. Data is no longer just something needed to run systems; it has become visible to many and is managed as a resource for the whole organization -- a corporate asset. Managing operational decision making as a corporate asset means treating it as strategic, managing it explicitly, making it visible and reusable across the organization, and improving it constantly.

Characteristics of Corporate Assets

A focus on operational decision making means treating decisions as corporate assets, which means ensuring that these assets have the following characteristics:

- Strategic. A corporate asset is strategic. Planning exercises consider how it can be used and applied to reduce costs, increase revenue, and expand the business. Ensuring that decision making is strategic means considering the process of making low-level operational decisions critical to the business and worthy of executive and management focus.

- Managed. Corporate assets must be managed, maintained, and kept in good working order. They must be reviewed and improved dynamically and continuously. Decision making is similar to equipment that needs constant maintenance, replacement of small parts, and upgrading. Because decisions must change and adapt, they must be managed.

- Visible. A corporate asset must be available and visible to management if it's to be used correctly. It must be understood as a competitive weapon and subject to reporting and analysis. Making decision making visible means managing decision making assets as you would other aspects of the organization's infrastructure, storing information about decisions in technology designed for that purpose, and making the use of this technology and supporting techniques standard across your organization.

- Reusable. Assets aren't casually duplicated or left idle but are reused and leveraged as much as possible. Decision making must be reusable across manual and automated processes and systems, internally and externally.

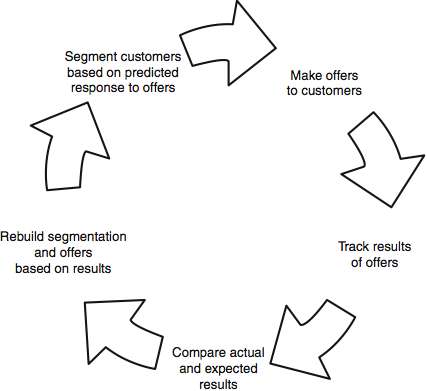

- Improving. Decision making must improve constantly; in other words, you must close the learning-improvement loop. Closed-loop decision making, as shown in Figure 2, enables you to capture results from production systems and put what you learn from them into a useful form rapidly. It means updating decisions based on your results or outcomes. Decision automation requires supporting all these steps.

Figure 2. An example of closed-loop decision making for marketing

Systems that can treat operational decisions as a corporate asset, deliver the best operational decisions, and ensure that those operational decisions reflect your business strategy are what we call Smart (Enough) Systems. Next time we will discuss the kind of system that would deliver this vision of operational decisions.

References

[1] McKinsey Global, "An Executive Take on the Top Business Trends." Survey conducted 2006. ![]()

[2] Business intelligence systems is used here to refer to reporting and analysis tools for managers and knowledge workers, while performance management systems are those driving more real-time monitoring tools such as dashboards. ![]()

[3] Q&A with Robert Kaplan, "The Office of Strategy Management," Working Knowledge for Business Leaders. Harvard Business School (March 27, 2006). ![]()

[4] Peter Drucker, "What Makes an Effective Executive," Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82, No. 6 (June 2004). ![]()

| Acknowledgement: This material is from the book, Smart (Enough) Systems, by James Taylor and Neil Raden, published by Prentice Hall (June 2007). |

# # #

About our Contributor(s):

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.