What Is XAI? The Ethics of XAI

Artificial Intelligence is technology that can be used in many ways. It can fake images, fake videos, and can make fake news. On the other hand, it can detect lies, detect cancer, and guide people using large amounts of data to make better decisions.

AI technology can be used for the good and for the bad.

This can't be a surprise because this holds true for many other technologies and tools that humans have invented. A simple tool such as a knife may be used to cut paper, eat a meal, or kill a person. A technology such as radioactive radiation may be used to cure cancer, create nuclear power, or make a nuclear weapon for mass destruction. Depending on the circumstances, we may judge the situation to be good or bad.

As a society we have developed a framework of moral principles to guide our behavior and help us make judgments about good and bad. The resulting institutions and methods are used to protect humanity from harm. Recent developments in AI have raised concerns over the ethical aspects of some technology. Even technology visionaries — such as Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Steve Wozniak, and Stephen Hawking — are warning that super-intelligence may be more dangerous than nuclear weapons.

What makes AI so different to raise such high concerns?

Amongst the concerns are the extent to which our legal institutions are prepared to protect us and the robustness of the methods to deal with the threats that this new technology may bring. There are political concerns as well, including the job market, skilled labor shortages, and shifts in the balance of power system. Some workers fear losing their job because of the shifts in the job markets, while European startups, for example, do not find the right resources internally and compete for expertise with the US and China.

Why would we consider that AI will take over the world?

Since the beginning of the computing age, people have tended to treat the computer as an intentional being. We can infer that from the language we use to reference a computer. Expressions like "the computer says no," "the computer is not cooperative today," "he must be cleaned," and "my computer loves to crash" are an indication that people attribute intentions to this technology.

AI solutions that are designed explicitly to appear intentional strengthen this phenomenon. These systems exhibit complex behaviors, usually seen as the territory of intentional humans, such as planning, learning, creating, and carrying on conversations. They seem to display beliefs, desires, and other mental states of their own. According to the philosopher Danniel Dennet, people assign intentionality to systems whose internal workings they do not understand in order to deal with the uncertainty about their behavior in a meaningful way.[1]

The fact that we assign intentions to computers may explain why one-third of the population would like a computer saying "I love you," as revealed by a recent study by Pega.[2] It may also explain why we feel an urge to protect ourselves from being guided, fooled, restricted, or manipulated by this same computer. Hopefully the group that wants a machine to say "I love you" coincides with the two-fifths of the population that believes "AI can behave morally" and the one-fourth of the population that believes "AI will take over the world." Why would we even consider such ideas? Aren't we good enough decision makers?

Is our reasoning capability so bad?

Psychological research provides proof that human decision makers have many systematic decision biases.[3] "Our reasoning is biased towards what we already believe" is a good summary of the research results, known under the name 'behaviorism'. Other, more recent research explains that these biases have evolved as strategies we use in order to distribute the work of 'good reasoning'. Experiments show that our reasoning capability improves when we reason together, "with each individual finding arguments for their side and evaluating arguments for the other side." We can conclude that reasoning is a social process, and the lonely thinker looking for truth and knowledge at the top of a high mountain is a romantic but false idea. To summarize,

- we tend to assign intentions to computers even though they are not moral beings,

- we are not very good decision makers, and

- our reasoning capabilities work best in a social process.

Given these observations it is a natural development to use technology to help us make better, more objective decisions.

Is AI our panacea?

There are reasons for concern when AI technology is applied on a large scale. These reasons relate to the differences between humans and computers and the effect on the pillars of our modern society:

- People attribute intentionality to AI systems to allow us to predict potential behavior without the need to know its exact working. But in contrast to humans, these centrally-programmed systems don't explain themselves and are not open to feedback. This prevents us from learning.

- AI is learning from the historical data that we created. We are biased so the data is biased, even if we do not know what biases are in the data. The resulting systems will have the same biases, and using them prevents us from unlearning our biases and from being egalitarian — violating the basic right of equality.

- Human reasoning capacities, collective intelligence, and society's ethical framework are based on conversation, independent information search, and diversity of opinions. AI is automating those essential capabilities; as a result, our societies' learning capacities will be limited towards the tunneled view offered by individual advertisements, suggested readings, and the repetition of our shared opinions. This limits another fundamental right in our society — freedom of choice.

Is our legal system fit enough to protect us from potential harm?

The European Commission takes these concerns seriously and has set the example when it comes to ethics guidelines.[4] They recognize that "To gain trust, which is necessary for societies to accept and use AI, the technology should be predictable, responsible, verifiable, respect fundamental rights and follow ethical rules."[5] They also warn about the 'echo chamber', where people only receive information which is consistent with their opinion or reinforces discrimination due to biased training data.

Trustworthy AI

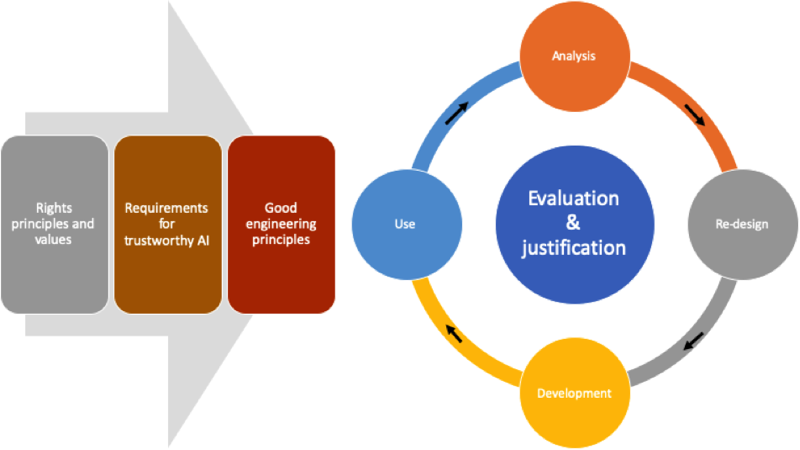

The resulting ethical guidelines for 'trustworthy AI' (published in the spring of 2019) are organized at three levels of abstraction:

- Ethical principles stated by general terms (such as AI algorithms) should respect human autonomy, prevent harm, and be explicable and fair.

- Guidance in the form of seven requirements on the way AI solutions are constructed or on their resulting behavior. Two of these requirements — transparency and fairness — relate directly to XAI.

- An assessment list that consists of questions that can be used to establish the trustworthiness of an AI solution.

All users and technology providers of AI solutions should be aware of these developments and be prepared, as these guidelines may become the norm. They will require AI solutions that have:

- the ability to trace a dataset and an AI system's decision to documentation;

- the ability to explain the technical processes of the AI system to humans;

- the ability to provide a suitable explanation of the AI system's decision-making process when an AI system's decision has a significant impact on people's lives;

- no biases in the data set, no intentional exploitation of human biases, and no unfair competition;

- implemented a user-centric design process by consulting stakeholders throughout the system's lifecycle, starting in the analysis phase and continuing by soliciting regular feedback after the system's implementation.

Figure 1. Realizing Trustworthy AI throughout the system's entire life cycle. (inspired by Figure 3 in [4])

This feedback loop is a well-known measure to improve and control any engineering process.

What else can we learn from traditional engineering?

Let's consult the famous article "No Silver Bullet" by Brooks.[6] He argued that "we cannot expect ever to see two-fold gains every two years in software development, as there is in hardware development." AI and XAI will not change this because his arguments still hold today:

- The fundamental essential complexity of engineering requirements in software design has not changed. For example, selecting the right level of detail, the mode of interaction with the user, and the explanation model differ per industry, topic, technology, and decision characteristics. Therefore, good engineering also applies to AI. The role of the business analyst remains important.

- The need for 'great' designers next to 'good' designers is still difficult to fulfill. Brooks' specific statement about AI provides a perfect example of this need. Techniques for expert systems, image recognition, and text processing have little in common. Therefore, the work is problem-specific, and the appropriate creative and technical skills are required to transfer the technology into a good application.

I support his recommendation to "grow" software organically through incremental development. His recommendation also aligns with the agile methodologies that are popular today and with the feedback cycles suggested by the guidelines for trustworthy AI.

Do's and Don'ts

The development of a code of conduct for the digital industry is one measure that many researchers, politicians, and leaders in the industry have asked for. It would have to be followed by anyone working with sensitive data and algorithms that guide behavior — a kind of oath for IT professionals similar to the way we authorize professionals in project management, medicine, accounting, and law.

But such a code is not yet in place, and it will take time to implement it with sufficient support by society and professionals. I have found many suggestions that list elements that should be part of such a code, with different levels of abstraction. Based on these, I present my top three do's and don'ts. Follow these do's and don'ts to decrease the concerns that exist related to using AI technology and to increase the ethical use of this powerful technology. But don't forget to continue, or start, following good engineering principles.

Top 3 Do's

- Do create a feedback loop between the human and the machine, and require an explanation for each decision that guides human behavior.

- Do de-centralize systems in a complex environment to make them more robust; balance different decision criteria, and anticipate changes.

- Do educate people about algorithms, raise the awareness about trustful AI, and focus on education that develops critical thinking skills instead of 'repetitive' or 'white-collar' task skills that will get automated.

Top 3 Don'ts

- Don't use data that has not been collected and enhanced with the intention to be used by machine learning algorithms.

- Don't filter information without making a user aware of the filter and providing the ability to remove the filter.

- Don't hide the data that has been used to feed, train, and test algorithms.

Needless to say, don't trust an oracle.

Three examples

The deceased artist Dali is talking to you — explaining about his life and making selfies with visitors in The Dali Museum (thedali.org) as if he is still alive. It's fun; people like it, and their learning experience in the museum has more impact. It is an improvement in the way we present and transfer knowledge and information. Artificial Intelligence (AI) technology made all this possible is what the promoting video tells us. Yes, in some sense that is true. A neural network is trained on old videos and pictures of Dali. The resulting model found patterns by Dali that could be mimicked. The technology used is a result of AI research.

This is AI technology used for the good.

The same technology can be used with good intentions but an undesired result. The most cited example is Google's algorithm that was trained to help in selecting new hires.[7] The result turned out to be highly gender-biased towards men. That was not the intention! Google's engineers are not stupid. They thought about this risk in advance and omitted including gender as a characteristic in the dataset …but a CV may list 'chair of the Women in Chess Association' or extracurricular activities like 'cheerleader'. The model picked up these words. And the result was a gender-biased model towards male hires. Why? The biases of our past selections are reflected in the historical data and, in the end, a neural network is just a mathematical function based on statistics recognizing patterns in the historical data used for training.

This is AI technology not used — because we did not agree with the outcome.

Whether and how Cambridge Analytica influenced elections is still a question for many people.[8] Setting that question aside, and supposing that Facebook's data was used legally, most people would still reject the idea of using that data to manipulate voting behavior — a form of 'big nudging'.[9] And that is what happened. Deliberately. How? It is not hard to imagine that there are patterns to match users with psychological profiles based on the words they use and the kinds of Facebook items they like. And that is exactly what an AI algorithm learned. Combine this with a model that relates psychological profiles with people's reactions to certain information and voting behavior. The combination is a recipe to manipulate voting behavior. The only thing you need to add is an individualized advertisement to target a specific profile with information that confirms their opinions to influence their voting behavior.

This is AI technology used for the bad.

Can AI ever make a moral decision?

An example of an often-cited moral decision involves three cats, five dogs, and a person driving a car. In this scenario, the dogs follow the traffic rules and have a green light; the cats do not follow the traffic rules and pass through a red light. The person in the car can either hit the cats or avoid them by hitting the dogs.

Most people will argue that hitting the cats and saving the dogs is the morally right choice.

But small changes to the situation may change their assessment. What if the dogs did not follow the rules? What if the cats are doctors on their way to save many lives? What if the car is a self-driving car?

When people make such moral decisions, we are not concerned. But it does concern people when a machine makes such a moral decision. Could it be that this concern is related to the fact that the machine cannot explain its decision?

References

[1] Jichen Zhu & D. Fox Harrell, "System Intentionality and the Artificial Intelligence Hermeneutic Network: the Role of Intentional Vocabulary," @ https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2ddc/1444e94cb0741305ab930cb54a09bf2688bb.pdf

[2] "PegaWorld 2019 Keynote: Rob Walker — Empathetic AI," @ https://www.pega.com/insights/resources/pegaworld-2019-keynote-rob-walker-empathetic-ai

[3] Ref. Daniel Kahneman, @ https://kahneman.socialpsychology.org

[4] "Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI," @ https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=60419

[5] "Coordinated Plan on Artificial Intelligence," , Brussels, 7.12.2018 COM(2018) 795 final, @ http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-15641-2018-INIT/en/pdf

[6] Frederick P. Brooks, Jr., "No Silver Bullet — Essence and Accident in Software Engineering," Computer, 20 (4):1987, pp. 10-19 @ http://faculty.salisbury.edu/~xswang/Research/Papers/SERelated/no-silver-bullet.pdf

[7] "Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women," Reuters (Oct. 9, 2018) @ https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G

[8] "Cambridge Analytica helped 'cheat' Brexit vote and US election, claims whistleblower," Politico (Mar. 29, 2018) @ https://www.politico.eu/article/cambridge-analytica-chris-wylie-brexit-trump-britain-data-protection-privacy-facebook/

[9] "Will Democracy Survive Big Data and Artificial Intelligence?" Scientific American (Feb. 25, 2017) @ https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/will-democracy-survive-big-data-and-artificial-intelligence/

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules