Decision Analysis (Part 2): The Basic Elements of Operational Business Decisions

This column is excerpted from Decision Analysis Using Decision Tables and Business Rules by Ronald G. Ross (Oct, 2010), an in-depth white paper available free on: http://www.brsolutions.com/b_decision.php

Decision analysis involves identifying and analyzing key decisions in day-to-day business operations and capturing the decision logic used to support them. Examples of such decisions are: Should a customer be considered gold, silver, or bronze level? Should an insurance claim be accepted, rejected, or examined for fraud? Which resource should be assigned to a task? Decisions like these are common in business processes.

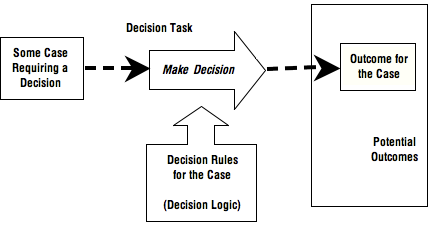

The basic elements of operational business decisions are represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Basic Elements of Operational Business Decisions

A case is some particular matter or situation requiring a decision. Example: John Smith — an ordinary applicant in terms of income, employment, and experience — applies for auto insurance.

A potential outcome is a result or conclusion that might be deemed appropriate for the case. Depending on the decision, potential outcomes might be:

- some form of yes/no (e.g., eligible/ineligible)[1]

- some quantity[2] (e.g., dollar amounts)

- some category (e.g., silver, gold, or platinum customer)

- some real-world instances (e.g., employees who are candidates for representing a gold customer)

- some course of action (e.g., on-site visit, teleconference, telephone call, email, FAX)

An operational business decision must always have at least two potential outcomes.

Business analysts should always endeavor to be very clear about potential outcomes. Shape and define them early; make sure they are not hazy or fuzzy; revisit and test them often.

The outcome is the result or conclusion deemed appropriate for a given case. Example: John Smith — an ordinary applicant in terms of income, employment, and experience — is deemed eligible for auto insurance (but could have been deemed ineligible).

A decision rule is a business rule that links a case to some appropriate outcome. Example: The decision rule that links the case of an ordinary applicant like John Smith to the outcome eligible.

The decision logic is the set of all decision rules for cases in scope of a given decision. Decision logic should be represented declaratively in the form of decision table(s), business rule statement(s), or some combination thereof. Example of decision logic: All the business rules for whether an applicant is eligible for auto insurance.

A decision task corresponding to this decision logic might be Determine Eligibility of Applicant for Auto Insurance. Quite possibly this decision task might be just one of many tasks in some business process. As Figure 1 illustrates, decision logic should be externalized from such decision tasks.

About Decision Tasks

Decision tasks, like all tasks, are procedural. A decision task does something; specifically, it makes a decision. Without some decision task, nothing happens — that is, no decision is made.

Decision logic indicates only what the outcomes for possible cases should be; the decision logic cannot actually make the decision. So there always has to be a task or action to make a decision. We take the necessity for such a task or action as a given. From this point forward we focus exclusively on development of the relevant decision logic.

Externalizing decision logic from decision tasks — a form of rule independence[3] — produces simple (or"thin") decision tasks, which in turn produces thin processes. It also results in decision logic that is far more accessible, adaptable (easier to change), and re-usable (e.g., in other processes). Overall, we believe that decision-smart business processes are the key to business agility.[4]

Naming Decisions

A decision must be named. The best, most business-friendly way to name a decision is using the business question it answers. Example: Is an applicant eligible for insurance? Naming a decision according to the question it answers:

- Assists in delineating scope. For example, the decision logic addressing the question above might not be about all kinds of insurance, perhaps just auto insurance. If so, the question can be sharpened to: Is an applicant eligible for auto insurance?

- Provides a continuing checkpoint for testing what the decision is really about.

- Serves as a constant reminder that the focus in decision analysis is on capturing declarative decision logic, not on how work is performed from a process point of view.

Forming, testing, and continually shaping the question that decision logic answers is essential for effective decision analysis.

We recommend the following conventions for expressing the question addressed by some decision logic:

- Avoid the word how. The interrogative how often suggests process or procedure. For example, a question worded as How should an order be filled? might be taken to mean "What steps are appropriate in actually filling orders?" Steering clear of any potential confusion with process or procedure is always best in decision analysis. Note that this convention does not apply to how much or how many, both of which refer to some quantity rather than some action.

- Avoid the word must in favor of should. For example: What should I wear today?, What sales tax should be charged on an order?, When should an appointment be scheduled?, etc. The answers provided by decision logic simply indicate appropriate outcomes for given cases. How strictly these outcomes are to be applied in actual business activity is a separate concern.

- Avoid discourse shortcuts (e.g., I, we, you, here, now, etc.). For example: Instead of What should I wear today?, write What should be worn today? Instead of “How should we price this order?, write How should this order be priced?

- Avoid and’s and but’s. Decisions with conjunctions are unlikely to be atomic. For example avoid: What is wrong with this machine and what approach should be used for fixing it? The and indicates separate decisions, each of which should be analyzed in its own right.

- Avoid words that are ambiguous or undefined. We recommend basing questions directly on a structured business vocabulary — i.e., a fact model.[5]

Part 3 of this three-part series examines how scope for decision analysis is expressed and refined.

Notes

[1] These actually represent facts — e.g., The applicant John Smith is eligible. ![]()

[2] a quantity that cannot be resolved or predicted by a formula or calculation ![]()

[3] Refer to Business Rule Concepts: Getting to the Point of Knowledge, 3rd ed., by Ronald G. Ross, 2009, p. 23. ![]()

[4] We define a smart business process as a decision-smart business process for which violation actions are specified for behavioral business rules separately, rather than embedded in the process itself. ![]()

[5] Refer to Business Rule Concepts (3rd ed), Chapter 1 and Part 2 ![]()

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules