The Five Basic Skills of Discovering and Expressing Rules

Extracted from Rules: Shaping Behavior and Knowledge, by Ronald G. Ross, 2023, 274 pp, https://www.brsolutions.com/rules-shaping-behavior-and-knowledge-book.html

What skills do you need to analyze formal communications to produce practicable rules in business and government? What does interpretation of source materials require?

This discussion identifies five basic skills you need. To illustrate these skills, it examines the following short bit of text from the policy manual of one of our clients whose mission is to pay claims for health care.

Cost Share Policy: The Health Program has a cost share policy. Clients are responsible for the payment of 25% of the cost of the benefit(s) to a maximum contribution of $500 per family per benefit year.

Like the majority of policies, the text seems deceptively simple and clear at first reading. Poke around a bit though, and questions quickly arise. The guidance is not yet in practicable form — not ready for deployment and implementation.

By no means is this assessment intended as a criticism of the policy. Creating sound policies, aligned with goals and strategy, is hard. Gaps and open issues are inevitable. It's simply our job to sort them out into practicable rules.

Skill 1. Developing Business Vocabulary

Ignore business vocabulary at your peril. Unaligned assumptions about the meaning of terms, and how they fit together, are perhaps the greatest source of misinterpretation and eventual rework in rule analysis.

Here are three quick examples for the Cost Share Policy:

- Where is 'claim'? The organization's mission is focused on evaluating and paying (or denying) claims, yet the term is not mentioned at all in the text. Why? When the authors wrote the policy, they probably simply assumed the context 'claims'. The omission, however, leaves a big hole in the meaning.

- Who is the 'client'? Apparently, claims are for health services performed for a patient. Is that correct? If so, is the client the same as the patient? Or someone else in the patient's family? Or someone else altogether? In what ways are people involved in the health-care activities?

- What is a 'family'? Who counts as a member of a family? You need to know in order to determine whether a claim 'counts' toward a family's cost-share responsibility. Hopefully, there are family facts (existing data) to go by. If not, capturing the rules for family membership can prove a particularly thorny area.

So, you need a structured business vocabulary to go by, with standard terms and definitions, based on a concept model.[1] It can be developed in parallel, and iteratively, along with interpretation and development of rules.

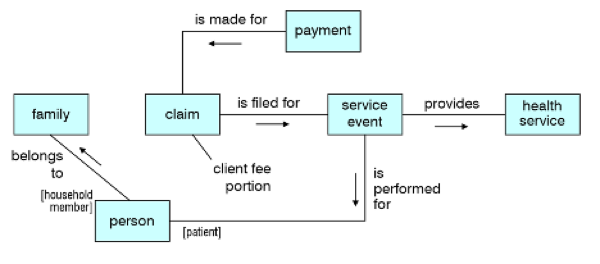

Below is the concept model diagram needed for analysis of the Cost-Share Policy. It's partial, but let's assume it's correct as far as it goes. Now you have a blueprint to navigate the concepts and to shape what you write. In the diagram:

- Noun concepts are indicated using boxes labeled by terms.

- Verb concepts are indicated using worded lines and arrows.

- Roles of noun concepts within verb concepts are indicated in brackets.

Figure 1. Concept Model Diagram Supporting the Cost-Share Policy

Skill 2. Capturing Embedded Computations

A trick in interpreting guidance is always to be alert for embedded or assumed computations. By spotting them and breaking them out early, you can simplify the remaining analysis significantly. (You can also use them to verify and refine your concept model.)

The Cost-Share Policy, for example, assumes the ability to compute 'contribution per family per benefit year' so it can be compared to the $500 threshold. So, a formula for that computation needs to be specified.

Using the concept model diagram as a blueprint, the following (almost practicable) definitional rule can be specified.[2] For convenience, terms in the concept model diagram appear in bold, and wordings for verb concepts appear underlined.

Computation Rule: The contribution per family per benefit year is computed as the sum of the client fee portion for all approved claims within a benefit year filed for each service event performed for any patient who belongs to the same family.

The sentence uses the concept model diagram as a structural blueprint. This may seem like overkill in expressing a single rule. Typical projects involving rules for government and business, however, often involve dozens, hundreds, or even more statements of guidance. Following a structured vocabulary is the price you pay for consistency and coherence across the whole set.

Above, I described this rule as 'almost practicable'. What's missing? If you examine the statement carefully, you can identify at least two shortfalls:

- What is a 'benefit year'? Timeframes and timing qualifications, of course, are always important. Is it a calendar year? Something else? As it turns out, this organization uses a special benefit year. So, we need to specify a definitional rule:

- How about 'approved'? How can you determine whether a given claim is approved? Can we assume we already have some fact (stored data) indicating as much? If so, no additional analysis is needed. If not, what are the criteria (definitional rules) for determining whether a claim is approved? That point of 'drill-down' could lead to a host of additional rules.

Definitional Rule: A benefit year is July 1–June 30.

Skill 3. Addressing the Core Guidance

Now that we have a rule for computing the contribution per family per benefit year, we can tackle the core issue the policy addresses: How much is the client fee portion for any given claim?

At first, the logic seems simple. The percentage is 25% if the family has not yet exceeded the maximum $500 for the benefit year. It's 0% if the family has.

The difficulty arises when a single claim in a benefit year takes a family over the $500 threshold. In that special case, the actual amount of the client fee portion is (probably) just whatever takes the family up to $500. So, for that claim, the percentage is actually less than 25%, but still greater than 0%.

That interpretation is an assumption. It's probably right. It's probably just a situation the policy makers didn't foresee or simply assumed would be understood. Nonetheless, the assumption should be verified with them in case they intended (or would want) something else.

Assuming the interpretation to be correct, this definitional rule can be expressed as follows. For visibility, the amount computed by the earlier computation rule has been shown in bold.

Client Responsibility Rule: The client fee portion for an approved claim is the smaller of the following:

- 25% of the claim amount

- $500 minus the contribution per family per benefit year at the time the claim is placed

Under this logic, the client fee portion is either 25% of the claim amount or whatever amount takes the family over the $500 threshold. If the family has hit the $500 threshold previously, the client fee portion is $0.

Note how addressing the 'embedded' computation rule for 'contribution per family per benefit year' beforehand greatly simplified the rendering and expression of this second rule. If that logic had been embedded in this second rule (rather than simply referenced by name), this second rule would have been much more difficult to capture and the resulting expression far less approachable.

Externalizing computational logic in the manner illustrated by the first rule has important benefits:

- It makes the logic re-usable by other rules not yet analyzed.

- It simplifies the expression of every rule that references it.

- It ensures the same logic is applied consistently everywhere referenced.

- It 'single-sources' the logic in case it changes, thereby improving its maintainability, and thus overall agility.

The rule of thumb is this: Computational logic should not be embedded in a rule if its result can be named and the logic expressed separately in another rule. Following this practice faithfully enhances the overall quality of a set of rules significantly.

Skill 4. Naming and Supporting Thresholds

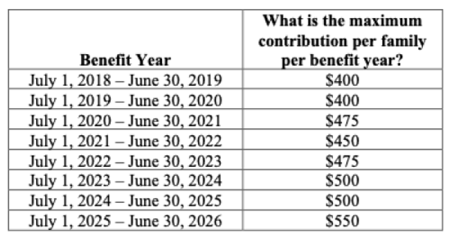

Central to the Cost Share Policy is the threshold $500. Thresholds, of course, are often used in multiple rules. They also have a way of changing over time.

To continue the idea of externalizing logic, two additional steps might be warranted, both to build on the advantages listed above.

1. Give a name to the threshold. For example, the $500 threshold might be called the 'maximum contribution per family per benefit year'. The second rule above now would be expressed as follows (with the new threshold name in bold):

Client Responsibility Rule: The client fee portion for an approved claim is the smaller of the following:

- 25% of the claim amount

- the maximum contribution per family per benefit year minus the contribution per family per benefit year at the time the claim is placed

2. Establish a means to permit the threshold to vary year-by-year. One means to support such variability is using a simple decision table, as the following illustrates.

Skill 5. Handling Exceptions

A common mistake that policy interpreters and analysts make in addressing guidance is to address exceptions earlier rather than later. It's a real temptation because the exceptions often present meaty challenges. And yes, there are almost always exceptions.

Addressing exceptions earlier rather than later, however, complicates matters significantly. First, adequate vocabulary structure and computational terms are frequently lacking to address them. Second, iteration is always the best way forward. Seldom if ever do you arrive at practicable logic in one giant leap. So, always get a handle on the 'happy cases' (the most routine) first.

Sure enough, the Cost Share Policy does have an exception.

Cost Share Policy Exception: Clients who are members of low-income families are exempt from the cost share policy.

Since this exception represents a policy, it should be treated as a behavioral rule:

Low-Income Family Rule: A low-income family must not be charged a client fee portion for any claim.

Then the earlier rule could be adjusted as follows:

Client Responsibility Rule: The calculated client fee portion for an approved claim is the smaller of the following:

- 25% of the claim amount

- $500 minus the contribution per family per benefit year at the time the claim is placed

- $0 if the patient belongs to a low-income family

Two revisions have been made:

- The result of the calculation has been renamed calculated client fee portion to avoid any conflict with the behavioral rule (Low-Income Family Rule).

- A third conditional clause has been added.

Thank your lucky stars! Exceptions often involve much more complexity than that.

References

[1] Refer to Business Knowledge Blueprints: Enabling Your Data to Speak the Language of the Business (2nd ed), by Ronald G. Ross, 2020.

[2] A basic RuleSpeak® guideline is to use the term for the number being computed as the subject of the sentence. That approach puts the 'heavy lifting' toward the end of the sentence.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules