Building Business Capability 2014 Decisioning Panel: Decisions from the Business Perspective

Building Business Capability 2014 Decisioning Panel

Decisions from the Business Perspective

Panelists

Roger Burlton Founder, BPTrends Associates Jan Vanthienen Professor in Information Management, K.U. Leuven (Belgium) Tim Evans Director, Product Operations, Bank of Montreal Financial Group Dr. Juergen Pitschke Founder and Managing Director, BCS Ronald Ross Co-Founder & Principal, Business Rule Solutions, LLC

Moderator

Kristen Seer Senior Consultant, Business Rule Solutions, LLC

- Should we architect language — not just document it but actually influence it?

- Are we using the word 'decision' to mean two different things?

- What are your recommendations for the use of business rules and decisioning in our transformation from being a traditional 'silo' organization?

- How much is data used in coming to an understanding of decisions?

| Welcome & Introductions |

| Kristen Seer: Hi — Good afternoon, everyone, and welcome to our business decisions panel. My name is Kristen Seer, and I'm going to be your moderator this afternoon. Welcome everyone! |

We have quite an illustrious panel assembled for you this afternoon. But rather than introduce each individually and talk about all their wonderful accomplishments — you can look all that up online — I'll point out just a few things about our panel members. When we start the conference Gladys always gives a list of the different countries that are represented at the conference, and this year we really found reflected in our conference quite a number of different nationalities. I thought this was rather interesting. On our panel, we have two Canadians — Roger and Tim. (I am Canadian myself, but I don't pick the panel members so that is just a coincidence) We have Jan and Juergen, from Europe — one from Belgium and one from Germany. And then we have Ron, who (as he mentioned this morning) is from Texas, where a lot of them think that is a separate country, but actually is part of the U.S. So on our panel we do have a good cross-section.

Another thing I find really interesting about this panel is that none of them really set out to be an expert in business decision. They all came to business decisions and decision analysis through different ways; they each took a quite different path to it. Whether it was working with processes and realizing "Oh, we have these tasks here; there's some heavy-duty decisioning going on that really has a big impact on the process!" Or whether it's operationally to say, "Gee, we keep getting different answers to the same question. Why is that?" Or, whether it's looking at a whole heap of rules and realizing, "Really, this set of rules exists to support this decision here." Or whether it's working with decision tables, which (given the name 'decision table') gives you a bit of a clue that it might have something to do with decisioning. Realizing the business thinking and the business criteria that need to go into making a decision, looking at it from that perspective, can help you format those decision tables in a much better fashion. So all of them have come to this area of business decisions — and I am emphasizing that it's business decisions — and they've all come at it differently. But they've all become quite expert in the area.

On that note, let me talk a little bit about the format of the panel. What we're going to do is have each of the panelists give a 4-6 minute presentation. It's going to be that short because we really want to get things opened up so that all of you can ask questions. Now that you've been at the conference for a day and a half, I'm sure there are a lot of questions you have on "What is this decisioning?" and "How does it fit with everything else?" It's a fairly small room, so we might be okay, but I do have the microphone and I will come to you with the mic when you ask your question.

I'm going to start off by turning things over to Roger to give his thoughts on business decisions.

Roger Burlton

Thank you, Kristen. You said that we all came to this from some other place. I was just wondering why you'd want to talk to a bunch of people who couldn't make a decision about decisions. <laughter>

Kristen Seer

These are the ones who have learned!

| Roger Burlton |

Okay. I'm going to talk a bit about how I've come to this.

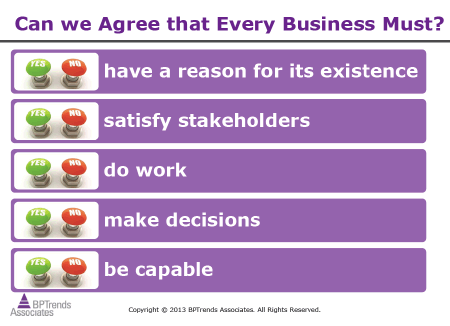

To set some context, I think that hopefully we can all agree that every business must (that's a rule, by the way): have a reason for its existence, satisfy its stakeholders, actually do something (do some work), make decisions, and be capable of doing all of that. If you can do all of that then you're probably going to be successful as an organization.

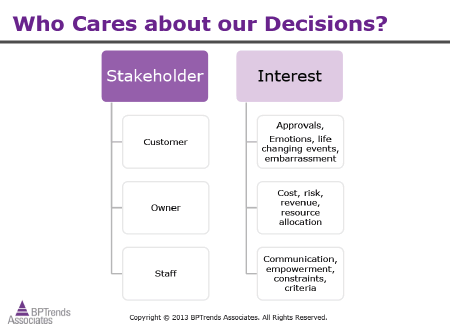

One of the things I always ask about (and those of you who came to my talk today know this) is the question "Who cares?" And so the question here is "Who cares about your decisions?"

Customers. Well, your customers certainly do because you're effecting things, approving things, on their behalf (or not). A lot of these decisions that we make, based upon what they're asking for, are very emotional for them. Quite often these can be life-changing moments for them. Or your decisions could be extremely embarrassing for them. If you turn them down for something, they have to tell everybody that they didn't get into that school or that they didn't get that loan. It can be very, very embarrassing to have to talk about it. So it's very personal — these decisions can be very personal.

Owners. From the ownership point of view we're making decisions all the time about where to invest, what's the cost, what is the risk associated with it, can we earn more money, where do we allocate our resources. Decisions are just all over the place.

Staff. Even from a staff point of view, they have to determine when to communicate, what decisions can they make (the level of empowerment), what constraints do they have, and what are the criteria by which they make the decisions. It's everywhere. It's certainly key to everybody we deal with.

So I'll share a few of the insights I've gained about this.

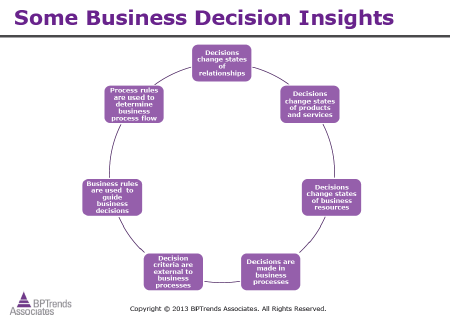

Starting at the top:

- Decisions change the state of relationships. I can make a decision and really, really lose my customer's point of view. Have you ever had a situation where you made a decision on behalf of your kids and they hate you? Especially when they turn about thirteen or fourteen? They hate most of the decisions you make. And so that is a big issue.

- Decisions change the states of products or services. Going from a 'good idea' to a launched product is a decision — a decision when to go live?

- Decisions change the states of business resources — things like assets and computer systems and various other policies or plans, when did they get approved?

- Decisions are made in business processes. For anyone who's drawing modeling diagrams (doing BPMN) you know to avoid the diamonds like the plague because the decisions are not made "in the diamonds" — those are gateways, not decisions. The decision is made in the process that precedes the diamond. Processes are where decisions 'live' — where you have to do it.

- The criteria for making the decision shouldn't be living in the process; it should be made prior to the process. It's part of strategy and policy. (I can't believe I'm agreeing with Ron so often these days!)

- Then, the business rules are used to guide business decisions. To me this is one of the big breakthroughs I've had over the last couple of years. We used to say, "Processes are guided by business rules." But, really, it's the decisions made in the process that are guided the business rules. That was a big insight for me.

- And so, business rules guide business decisions, and process rules are used to determine the actual flow of the process — where you go next.

So, decisions are all over, and they're actually quite critical.

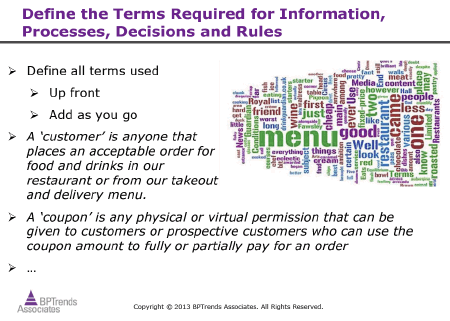

In order to do all this you've got to come back to the foundation — you have to define what you're talking about: What is a customer? What is a coupon? One more time I'm agreeing with Ron. (This is insane!)

You have to get it really crisp as to what that means; otherwise you can't use the rules, otherwise you can't make the decisions. Actually, it's not that you can't — you do — but it's not very consistent or reliable.

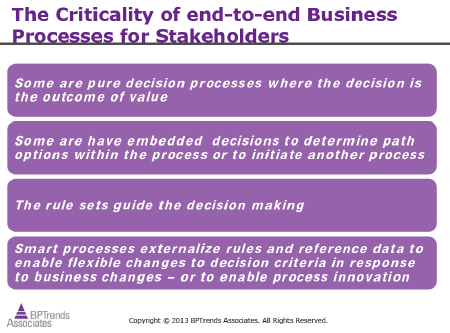

The critical end-to-end processes are something like this:

Some decisions are pure decision processes, where the decision is the outcome of value. For example, yesterday Tim gave the example of granting credit for a mortgage. Everything up to that point-in-time leads to the decision. And knowing the answer to that decision is the outcome. It's critical.

Some decisions are embedded, to determine what way to go next: I'll go Path-A vs. Path-B; do I send this to a supervisor, or do I make the decision myself? You need rules to guide that decision making.

Smart processes externalize rules and reference data to enable very flexible changes to the criteria. Because as the business changes you need to be able to do that.

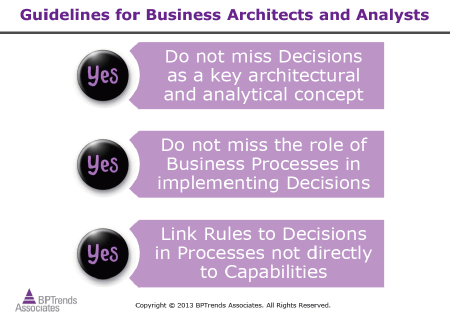

Ultimately then there are a few guidelines for architects and analysts:

- Do not miss decisions as a key architectural and analytical concept. In all the work we are doing in business architecture, we're now actually putting in decision structures, decision models, as part of the architecture — and not just as something that happened to come along. A year and a half ago we wouldn't have thought about that — we would have just gone right to the business rules.

- Do not miss the role of business processes in implementing decisions. It all comes together there.

- Link rules to decisions in processes, not directly to capabilities. What I'm saying here is that the rules get executed in the work that you do. You have to be capable of making the decision, of course, but the decision is made in the context of the outcome you're trying to decide upon.

| Jan Vanthienen |

So, rules, decisions, and processes. I've been doing decisions all my life. The names keep changing, but I'm doing the same thing. Sometimes it's called 'decisions' — or 'decisions in processes' or 'operational business decisions' or 'decision models' or 'DMN' — but I'm still doing the same thing.

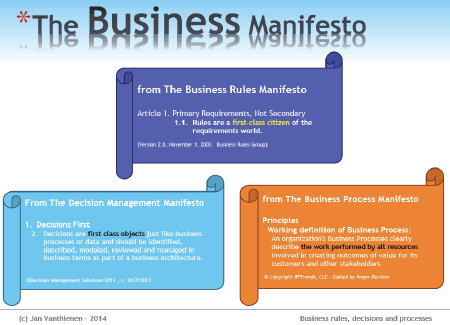

All right! Rules, decisions, and processes are the three things we're dealing with. All of the three are important. Roger has already said that; Ron will say that; everyone will say that. We have three Manifestos; all three of them are important.

The question, of course, is what is the difference and how do we deal with it?

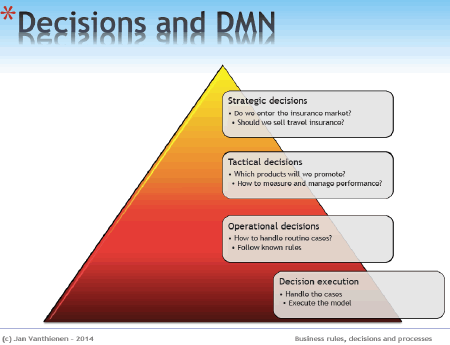

Which decisions? In my case, it's the simple, operational decisions — the recurring decisions that happen every day. Not the big strategic decisions, tactical decisions, but the operational decisions for the routine cases. (Exceptions can also be routine cases, by the way.) That follows the pattern in business rules: operational business rules.

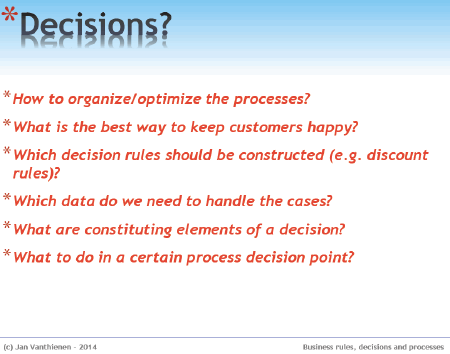

So we try to answer some of these questions.

For example, the second-to-last question: What are the constituting elements of a decision? A decision consists of some other decisions, sub-decisions. What to do at a certain point in a process — before the 'diamond'? Where did the decisions/decision rules come from? What are the guiding business rules? (Because a decision is not the same as the rule.) Which data do we need to handle these cases in a decision?

These are all important questions.

Another tough question is how to organize/optimize the processes in a business? That's not the type of decisions we're talking about. Or "What is the best way to keep customers happy?" Again, important decisions for business, but not the operational decisions.

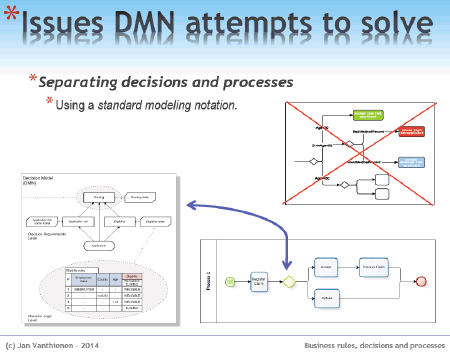

What you see is that we have standards for processes; we have standards for rules; we have standards for most things. But we don't have standards for decisions. And that's why I wanted to talk a little about a standardization effort, Decision Model and Notation (DMN), because we want to express decisions. We know what decisions are, but it's hard to communicate decisions if you have no standard for communicating them. That is what DMN is about.

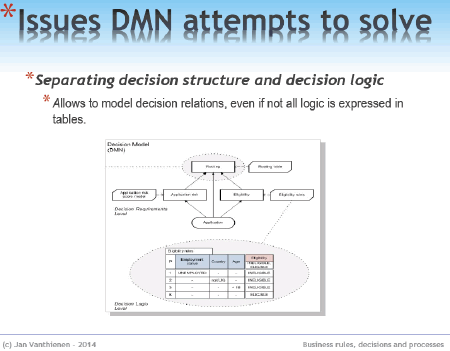

We understand that [referencing the right part of the picture, bottom of the slide] there is a standard here. But we didn't have a standard for the decision part. And, of course, we have to separate the decision part from the process part. We don't want these decision-tree-like things [referencing the top of the page] — that's too complicated. We want the split, and therefore we want to be able to communicate both elements. So the decision model [on the left] will link to the process model. That's one of the important observations.

The second important observation: When you model a decision — it takes some time, sometimes, to model a decision — there are two layers.

There is a top layer (the decision structure, the decision modeling layer), which is about requirements, questions, relationships between questions, Q-Charts, and other similar things. And there is a bottom layer, which is the decision logic itself — the representation of the rules. It's important to distinguish these two levels: the bigger requirements level, and the small and difficult detailed level.

Another thing DMN attempts to do as a standard is to not present a methodology but only to make methodologies possible.

There are enough methodologies. But in order to communicate it's nice to enable the methodologies. We should keep the insights from the past — good decision table models, good decision models — and not throw that away.

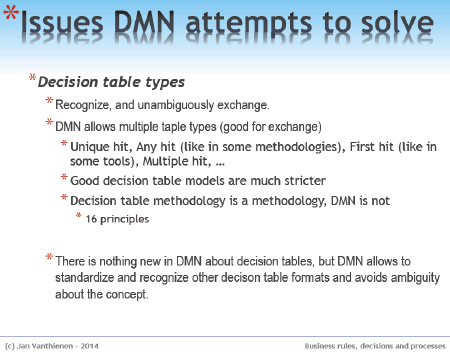

In DMN there is this whole thing about there being different kinds of models and tables, and people will automatically say, "Why do we need all these types?"

Well, we don't 'need' them; we just want to recognize them. If some of the users/modelers/vendors use a specific form or notation, we want to recognize it to ensure clear communication. That's it. There will always be differences, just as there are with "The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly" decision tables. But at least we recognize them, and that's very important.

There really is nothing new in DMN except the fact that we can standardize it, we can recognize it. By the way, if you are awake tomorrow at 8 a.m. there's a keynote about these topics, and I'll be there if you are there.

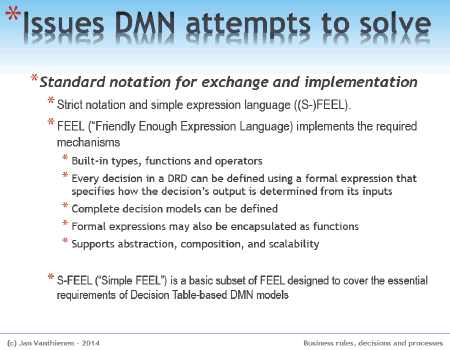

What DMN tries to solve is to standardize some things: standard notation, standard exchange, an expression language for business people to be able to say things like "If the date of an order is smaller than this-date, …." That requires some business language because dates have to do with Daylight Savings Time and hours in regions and so on. So we need to make communication very clear.

| Tim Evans |

I'm one of the practitioners on the panel. I never set out to become an expert in business rules and business decisions. But I do use them because generally I am trying to make things better and this is an important way of trying to do that. So, I'm not going to talk as much about a framework as I am going to share some of my observations as a user of business decisions over the last year.

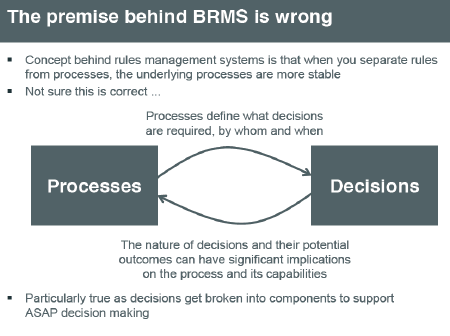

For my first point I will perhaps try to lean a bit toward the controversial side: I actually believe the storyline behind business rules is a little flawed.

You'll hear a lot of people say that if you pull the rules (the decisions) out of the process then it makes it much better because I can tinker and modify the rules/decisions and my process stays relatively stable. I would say that in the last year of having used that I think that's wrong. I think that when I define a decision — and I define what the outcomes are that come out of that decision — if I start changing up what the potential outcomes are, it can have very significant impacts on the process that it lives within.

I gave an example yesterday — a credit card example. Let's say I have a typical credit card model: apply for a credit card, and get a letter with either a credit card in it or a decline letter. I might move to more of a negotiation model — like a corporate loan: "Will you give me this?" "No, but will you take that?" By simply changing up the outcomes in the decision in this way, it's a very different process that it exists within. And the competencies and all of the things that need to be there around the people who are doing it also change quite dramatically.

I think what happens is the spots where people try to say that "Well, I can change it up without impacting the process" they've actually made a whole bunch of very inflexible decisions around how their thinking works, and they're really just changing parameters. I would challenge people to rethink that. I think if you do start looking at your decisions it is simplistic to assume that the process doesn't change when you start changing how those decisions work.

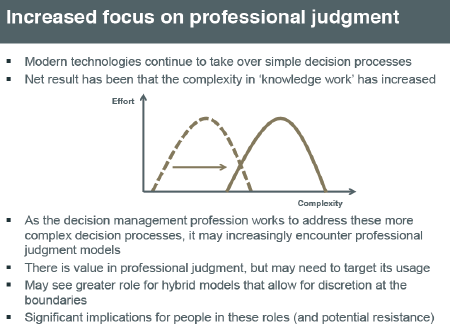

The second point that I'm seeing as a challenge for business decisions from a practice perspective is having to tackle the issue of professional judgment.

There's a chart, which I've simplified here, that I've seen used in my industry. They say, "We've done a really good job of automating, and a lot of the simple decisions have been automated. The opportunities for new areas to apply some of these technologies are getting more and more complex."

As a rules or decision profession if we're trying to build capability to automate, or at least provide some form of guidance to, how the knowledge worker or the professional does their work, we're going to have to tackle some of the areas that have a higher degree of complexity. How we're going to try to layer that in will be pretty important. I can start to see a role for hybrid models, where you try to take the easy ends of the decision spectrum out but still allowing some discretion, potentially, with the fuzzier boundaries in the middle.

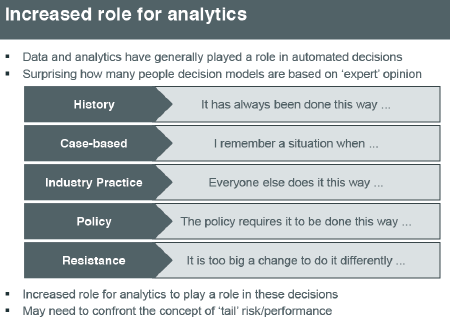

The last point I wanted to bring up is that this "Big Data" thing that is starting to hit everywhere.

Big Data is going to start hitting the decision space. Now I think you'll find a bunch of decision people who will say "We're been there. We're leading the charge!" because there are these great models. But anyone who has looked at (say) Netflix's recommendation models will say, "Yes, we do use a lot of data." But I think that's a bit simplistic. I think that there are a lot of decisions that have been made where there has not been a lot of data applied to it.

You can see some examples. Ask: Why do you approach the decision this way? And the answer given is "It's always been done that way." How many times do people know of factors in decisions not because there was this Big Data analysis that said that's the way to do it but because something went wrong. And so the natural reaction when something goes wrong is to create new rules to ensure that that wrong thing won't ever happen again, without any analysis to say whether or not this was simply an isolated case.

We hear: "Everyone else does it this way." And "The policy requires it to be done this way." And the one I always love, "You may be right, but that's just too big a change." Even in the spots where people have brought data in to help calibrate decisions, what I see a lot of the time is that while they're totally open to the data providing different parameters they will religiously defend to the death the model. It becomes an interesting conversation.

So for my third point I would say that bringing in analytics is a big thing that we're going to need to look at. I think that in the last year, in a lot of the decision work we've done, there have been a lot of 'urban myths' within the organization that we ended up busting by bringing in data.

| Juergen Pitschke |

I'm Juergen and, as Kristen had already said, I'm from Germany. I often start with the statement that I'm an engineer and maybe, for some of you, that's the same thing: If you come from Germany you have to be an engineer. <laughter>

In the context that we are talking about, what is an 'engineer'? An engineer is somebody who is doing engineering. To quote a favorite book of Ron's, Merriam-Webster: "engineering is the world of designing and creating large structures or new products or systems by using the scientific methods." The things from guru scientists are used by the engineer and he makes them practical. In short, the engineer is the real hero, not the scientist.

Originally I started (as many others) with process — Business Process Management (BPM) and I found my way to rules and decisions. Even if you look, today, at what we do in process management, many things are inspired by production ideas, production processes.

But in reality we have many more customers coming from the service world. This gives us different challenges and we have to "think different."

Tim already mentioned that he is questioning a lot of things that are coming from the traditional process mentality and I can only agree. I was at a conference last year where there was a lot of talk about Six-Sigma. One of the attendees was a Lufthansa pilot who said, "What are you talking about? Six-Sigma means every two days we have an airplane crashing! We have to talk about Zero-Sigma."

To "think different" — to challenge what we do every day — is also true for the rules and the decision world, yes? If you look at what happened in 2014 an important step was to get DMN … not released yet but, hopefully, soon.

This got us a lot of attention, much more attention than before. We got new types of customers interested in business decision management.

But we don't want to have only interest. We want to have buy-in. So what do we have to do? We have to teach people how to do this, how to apply it to the reality. We also have to challenge the business decision world. In the middle of the year I taught a workshop, and I had a lot of people attend who didn't come from business rules thinking. I realized I had to use different words. So I redesigned the course, not to replace the old workshop but to create a new workshop for people coming from another world, one where different words are used. There are different concepts, and things have to be explained in a different way.

We not only got interest from new types of customer, we also got a lot of interest from new industries. Many examples we see are from banking and insurance. I also do a lot of work in logistics and in other industries, and there is a lot of interest from such industries. I have a customer that I educated for a long time and this year he really became interested. He came back to me a month ago and said, "Oh, Juergen, now I see decisions everywhere!" So he's really a fan now.

For my last point: The panel is called "Business Decisions Panel" but DMN is also addressing the implementation of decisions, or helping you to implement the decisions.

I think it's really important that you include your IT. Business people usually involve IT, saying, "Oh, I want to have this implemented. I want to have this supported or automated." But they don't like it when it's done the old way, taking too long and being too inflexible. We find it's always good to include the IT people early enough so that they can redirect this. We did a project in Austria where we did a kind of 'inverse Scrum'. In Scrum you usually have a business person on the team when you implement. We did it the other way around — we had an IT person on our business team. He was able to react early enough to make sure that what we analyze and design is implementable later.

Ok — thanks. And now I'm very curious to see if Ron can only talk about rules or can he also comply with rules about timing. <laughter>

| Ronald Ross |

The timing doesn't start until I do the first transition here. <laughter>

Seeing decisions everywhere you look — is that a good thing, or is that a bad thing? There are decisions; you can find them everywhere. You can find them at the operational level of the business; you can find them at the tactical level of the business; you can find them at the strategic level of the business. You can find organizational decisions, and you can find personal decisions. You can find government's decisions; you can find IT decisions; you can find project decisions.

So sometimes I question whether a word with such broad applicability is actually that useful. Or to say it differently, is there some finer way that we could look at the problem to narrow in on what we're actually trying to get at? I've become a little bit disenchanted with the word 'decision' — more perhaps than I was last year.

This is a somewhat different look at it than the other panelists. The idea is to give as much range of perspective as possible so that we can trigger some questions.

So let's look at the spaces that 'decisions' apply to.

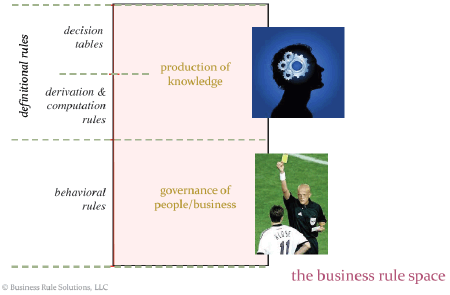

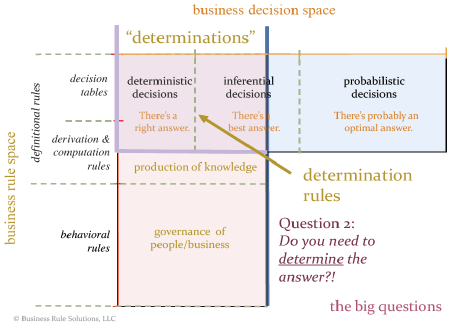

First, I want to look at the business rule space.

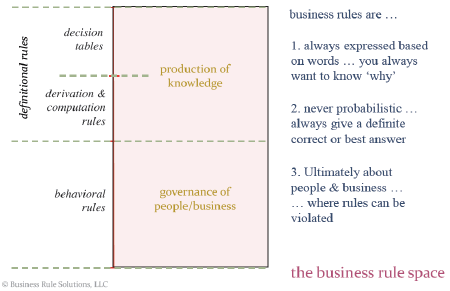

As I've mentioned in my other presentations, according to standards (and just common sense) there are two fundamental kinds of business rules — not one.

There are behavioral rules: those are rules that guide people's activities or organizational activities. You can violate those rules — just like a referee intervening, in a soccer or football game, in order to give a penalty or reset the play. These are fundamentally distinct. And frankly I don't think most software vendors have stepped up to supporting these in a way that business and business analysts really require.

The second kind of rule in the business rule space has to do with (essentially) decisions. So I say "production of knowledge" — you can talk about decision tables, which are collections of rules; you can talk about derivation and computation rules. But they all really have to do with knowledge and identifying what you can decide from the facts that you already have in front of you. You can't violate that kind of rule; you're just creating new knowledge.

Now if we look at this space, what you're going to find is that words are always important — what words you choose; what words you use; how well you define those words — because you want to know the 'why'. As I talked about in my keynote it's always about why you get this result, this business result. I talked about the why button — you have to be able to explain the why.

I also do not believe there's such a thing as a probabilistic business rule. I just don't believe it. That's not the way businesses work, based on probabilities, unless you're talking about marketing and trends and profiles. But that's a different question. When it comes to compliance — when it comes to coherence of outcome — it's not probabilistic. There's a right, or a best, answer. And that's just the way it is.

So I think that business rules are ultimately about people and business. What's different about business rules versus the semantic web is that rules can be violated, at least behavioral rules.

Now let's look at the decision space.

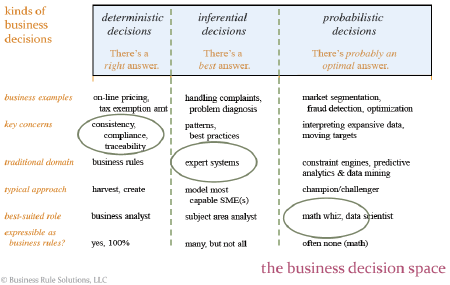

Here I see three different areas within the business decision space.

There are deterministic decisions, for which there is a right answer. You want that right answer because the important objectives for those kinds of decisions are consistency, compliance, and traceability. You must know why; you must have why traces; you must be able to prove compliance.

Inferential decisions really have to do with when there is a best decision — not necessarily the right decision but a best decision. I think this is where expert systems and production rules and the kind of platforms that came out of the 80s and 90s (and are still around) have mostly focused.

Finally, I think that there are probabilistic-type decisions, where there's not necessarily a right answer or a best answer but there may be an optimal answer. You're trying to optimize (with data and so on), in a very complex situation, in order to find what the optimal answer is. This gets into Big Data, and that's important.

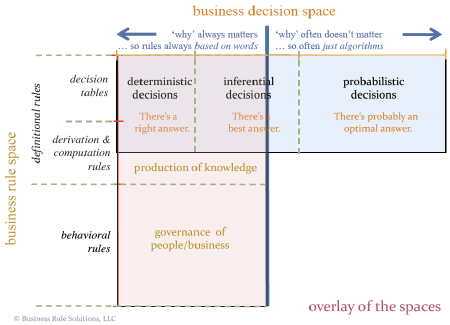

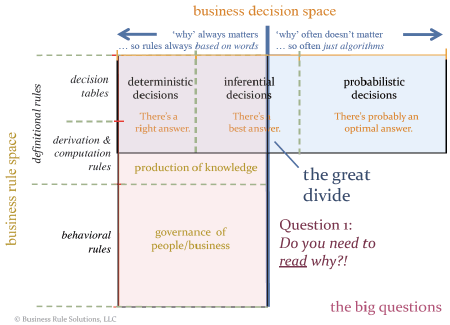

If we overlap these two spaces … they don't coincide.

I'm sorry that this isn't neater, but really there is a major divide between the two spaces. They are just not the same space.

First of all, in the business rule area there is always the need to look at words so you can explain why.

On the right, for the probabilistic decisions (in particular), you don't have to explain why; you just want a good answer. So the first question is: Do you need to be able to read why? If so, that's going to lead you to business rules and written kinds of expressions.

The second question is: Do you need to determine the answer? — the best answer, the right answer.

What I've come to believe is that for the business rule space (which is this vertical space) I'm not even sure that 'decision' is the right word. And so we've started talking about doing 'determinations' because that's what you're trying to get at, a determination, and thinking about determination rules in order to arrive at those determinations.

A final point. I didn't make up these words. Actually they come from Oracle OPA (Oracle Policy Automation). They have been doing this for a good while, and it's a very nice way to look at the world. Look for more of this kind of focus in days and years to come.

Kristen Seer

Thank you very much, panel. You all did very well, staying within the time.

Now I would like to open things up to the floor. I'll run around with the mic so just raise your hand if you have a question. And if you want a particular person to answer, let us know that. If not, they'll probably all jump in because you know these are very opinionated panelists! I'm sure they'll each want to say something.

All right. Who has our first question?

Ronald Ross

I think the answer is that it depends on the problem space you're looking at. If you're talking about compliance with policy, then you're talking about determinations and words are everything. For that it is important to try to converge on a set of words that communicate so that other people, displaced by time and place, can understand and relate to — so that you have a clear expression of knowledge. It's about the capture of knowledge and including that knowledge in the payload of the business architecture.

But there are a lot of problems where that is not important to do. If you're trying to identify trends in profiles — say you're going to use IBM Watson to look at Twitter tweets over the last two years to gain some novel insight — I don't really think that necessarily needs to be put into words. As long as you can communicate it in some way that makes sense to somebody, nobody really cares how you came up with it. There it's just the insight that's important. So that's a different problem — one where words and precision matter a whole lot less.

Roger Burlton

I would say that if there are any words that show up elsewhere in the architecture then I would architect the language because you're going to try to communicate and for that you need to have a consistent understanding.

Tim Evans

I come from the business side, and the thing I would say is to be careful with the language. One of the problems I see is: You're trying to talk to a business audience and you want to talk to the business audience in your language. But if you really want them to listen and pay attention you really need to talk to them in their language.

When you do hit terms where there's confusion around them you'll find they're interested in having that conversation. But architecting the language to try to get them to understand what you're saying? Or to architect the language simply to have it architected? That generally will very quickly turn off a business audience.

Kristen Seer

I think we do that when we say 'determine' for the action and then the outcome is the 'decision' (or the 'determination'). Is that what you're talking about? To differentiate the action from the outcome, the decision itself.

Ronald Ross

The convention we follow in process modeling is we always use the key word 'determine' and then say, "determine something," just so that you can identify, in the process model, which of the tasks are decision-making tasks.

Also, we are very careful to separate action-type tasks — where something is being done — from decision-type tasks — where nothing more is being done than just identifying the correct or best or optimal answer.

Kristen Seer

Okay. Do we have another question?

Jan Vanthienen

Paying attention to the decision points (or 'emphasis points') in the process is going to be the first step in identifying places where there is some decisioning going on. Then you can work to isolate what's happening. Instead of having the diamonds and the double diamonds and the cascaded diamonds, try to isolate an area and say, "Okay, here is a decision going on."

Then ask: "What is the decision?" What are the criteria? What are the requirements? What are the data? As you talk about this you will become more accustomed with modeling the decisions at different points in the process.

You don't have to struggle with figuring out "Is the process determining the decisions?" or "Is the decision determining the process?" By just doing these things separately this will start to come out naturally.

Roger Burlton

One of the things to look for is any state change. For example, with 'order' you can have a submitted order, an approved order, a scheduled order, a shipped order, a received order, a paid-for order. Every one of those points probably has a decision happening somewhere. Any time something changes status, have a look there to see how you determined that the status change should be made. There will be a decision in there somewhere.

Juergen Pitschke

You can start with the process first, but you may find that you come to a point where you have some problems. I worked with a client who was doing financial help for students. We had a lot of process models, but it seemed absolutely fine — it worked fine. The problem was that we had forty-eight business process models for approving an application.

Why forty-eight? Each model looked quite good and was maintainable. But why forty-eight? Because we had forty-eight different programs! So the problem was not in a single process but in all the combinations. When we tried to define a new program for students we had define a new process because there was something hidden in this process.

So they asked me for help. After two months I asked them, "Did you learn something?" And they answered, "Yes! We don't do process any longer; we do something different." What they were doing was decision management. We described the decision for approving an application for a special program separately from the process, and without consciously knowing it we started to go into rules and decisions.

Ronald Ross

I forget which of you guys said this but I think to some extent we all agree on it: These days the focus is increasingly on white collar work, as opposed to industrial, physical, mechanical work. And this is not the same thing. It just doesn't act the same; it doesn't model effectively quite the same.

The thing we really need to focus on for more white-collar-type work is not so much the flow of the process but the collection of milestones that you reach (or state changes, if you prefer) and the identification of the decisions that allow you beyond those milestones. I think that will increasingly be the way we look at and think about things.

And one more thing before you take the mic away from me…. In order to address processes you have to cross organizational functions. You have to break down semantic silos. In other words, you have to address vocabulary; you have to address semantics. One of my disappointments is that DMN doesn't really do anything with semantics. I think that, in today's world, that is a shortcoming. (I'm just trying to get a little controversy going here. So I'll hand the mic back [Jan's] direction.)

Juergen Pitschke

I completely agree. For service type processes you need different things than before.

Another hype we currently see is CMMN, Case Management Model and Notation. We hear a lot that from them that processes are completely adaptive, completely flexible. But that's not where the reality is. There are a lot of different stages in between being totally prescriptive and totally adaptive.

On Roger's slides he had one important type of decision that is to decide how you proceed — which activities you choose for some special case. And that's not free; you as a worker are not free to come up with this. You have still to comply with certain things. So that's an important type of decision that can help us make our processes much better, yes?

Tim Evans

If I understood your question, you're doing a large end-to-end engineering. You're trying to now be a bit smarter around decisions and rules because you've come here and we've told you that you should be smarter about how you do decisions and rules. How do you layer that in?

I'm the practitioner so I'll give you three bits of advice.

First, you're not going to tackle every decision. You're going to have to look at what are the core problems. Roger would say to look at what your North Star is. Ron would probably talk about strategy and motivation. You're going to have to look at what are the decisions you really need to look at because they're integral to what you're trying to work on. There will be a whole lot of other decisions that you may not get to on the first round.

I did a project where we were looking at credit approval so we spent a lot of time on the credit decision. We spent no time on the pricing decision because that wasn't what the perceived problem was.

The second thing is: All this stuff is iterative. What will happen is that as you look at one decision it may start taking you in the direction to look at other decisions. But trying to imagine that you're going to get it all done perfectly is impractical. And even if you did do it perfectly, in three years' time some disruptive innovation is going to hit your industry and then it won't work anymore. So, just recognize that element.

And the last thing is (before I hand the mic to Jan so the DMN and RuleSpeak folks can duke it out): We've talked here about BPMN and BMN and CMMI. As the practitioner, I would give the caveat that the business audiences you're going to talk to will know none of this terminology. If you try to "over technify" — if you get them too hung up on the framework and the technicals of it — what you'll be losing is the real business discussion that these are trying to bring to the fore. So you can use these tools as a practitioner, to try to identify this stuff, but remember you've got to re-express things in a way that the business audience can engage in. Don't forget that what you really want to do is have a meaningful conversation around what the decision is that they are making and how they are going to go about making that decision.

Jan Vanthienen

I can only agree with that!

First about Ron's comment. There was already such a good standard about semantics, SBVR, that DMN didn't want to touch it, or improve it, or make it worse. That's my simple answer. <laughter>

Okay. I think the question is not about 'decision'. The question is fairly often about "What do you mean by 'business process'?" Very often if I hear the term 'business process' (not from you, Roger, but from other people) it's about the process of making a decision. But that's only part of the business process. That's the decision process. We are also talking about steps, and acquiring data, and sending some messages around — with the final goal to make a decision. But that decision is embedded in a business process.

So we are talking about processes at two different levels. When you say, "The process determines the decision" I agree. But at the same time, "The decision determines the decision process steps." That's another layer.

Next year we should have a panel about process, the meaning of 'process'. Because I think decisions are clear now. <laughter>

Kristen Seer

Okay. Let's move on to the next question if everyone's okay.

Jan Vanthienen

In the process mining space we've just started a workshop on decision mining, which is very similar — trying to mine the activities before the diamonds in the process. So we might find we're talking about the same thing again, just using different names. We will have to solve that. But I think it's very similar.

Juergen Pitschke

A year ago the Hasso Plattner Institute, in Germany, started a research project on how to identify decisions in a process. We will be watching what comes out of this. If you want to participate you can go to their website [http://hpi.de] and submit models about processes to go into this research project.

Tim Evans

I'd look at two answers to your question.

Is data used to make decisions? I think the real answer is, "It depends." I think there are some spots where a lot of data is used to make decisions: What books Amazon recommends to you; what pricing you get — there's often a lot of data behind those systems. But I think there are a lot of decisions, actually some of the more interesting decisions, where there isn't any data; it's done that way because we've done it that way for twenty years and nobody's ever gone back and revisited that decision.

Another thing I would mention that is really interesting can be summed up by a great quote a number of people have had in their presentations: "In theory, theory and practice are the same, and in practice they're different." <laughter> There's the 'how you've stated you're making the decision' and then there's the 'how you are making the decision'.

I'll give an example from what we did: We had this great rules engine; we had all these rules. We turned around and said, "These conditions are spots where we don't really want to approve somebody for credit." That was the theory. The practice was that 99% of the time, if the theory said "no," they would override the theory. They would try to force it to a person who would figure out a way to approve it anyway. Almost all of these cases got overridden — two thirds of them eventually got approved, potentially different from where they originally came in but they got approved anyway.

So I think it's interesting to look at not only how people are using data but it's also interesting to consider that how you think they're making the decision and how they're really making the decision may be very different.

Jan Vanthienen

I only want to add one sentence to what Tim said: "There's nothing as practical as a good theory." That's what we say in academia. <laughter>

Ronald Ross

I want a quick clarification — a follow-up question: I have some confusion about whether you guys are talking about 'data' and meaning the same thing. So, Tim, when you gave your original talk I wasn't 100% sure what you were meaning by 'data'. Were you talking about performance data, essentially measuring the quality and effectiveness of decisions as have been made in the past? Or were you talking about some other kind of data?

And [to the audience member] in your question, when you say the mining of data, I wasn't 100% sure what you were talking about — what 'data' you were talking about.

So this matter of semantics and meanings and words — it's always an issue. I'll just leave that as a question.

Tim Evans

Specifically what I was thinking about, in terms of my example, is that when you build a decision you make a lot of assumptions about how the world works. But that may not be the actuality of what's happening in the world. I think people take a lot of mental shortcuts in arriving at decision logic. In a lot of cases people don't realize it or don't check it. The number one thing said about assumptions is that the first thing you should do is move from assumption to fact. But for a lot of decisions that's rarely done.

Roger Burlton

I would add that, quite often, this is an issue because the strategy and the policies are not translated into decision criteria leaving humans to make up their own criteria. So we have a mismatch between the intention (what's intended) and the actuality (what happens).

Tim Evans

Something I've seen on a lot of slides is: Culture eats strategy for breakfast. I'd like to ask: Does culture eat policy for breakfast?

Roger Burlton

Culture has an insatiable appetite. <laughter>

| Wrap-up |

| [Kristen]

Is it all right if we end on that note, guys? Because we have run out of time.

Thank you all very much for your participation. And thank you to our wonderful panel for all their thoughts and experience. <applause> |

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.