Mind the Gap: Practical Process Governance

I previously wrote about process performance management and how that is fundamental to effective process-based management. Of course, that measurement is pointless if it does not lead to action. Measuring just for the sake of measurement, even if it is reported in a fancy dashboard, is waste. There must be appropriate response to the measurements. Process measurement must drive and confirm change, not just create reports. Who is going to do that? How should it be done? How can we avoid creating continuous conflict between functional and process managers?

Much has been written about organizational and process/BPM governance. Had he been alive to this discussion, Mark Twain may have commented, as he did elsewhere, that "The researches of many commentators have already thrown much darkness on this subject, and it is probable that, if they continue, we shall soon know nothing at all about it." I'd like to break out of that spiral dive with some pragmatic, if a little controversial and perhaps counterintuitive, suggestions.

Process governance is one of the 7Enablers of BPM that get the circles turning. It is an area where we need more clarity and simplicity. Let's walk through what I think is meant by process governance and how it can be achieved and sustained in a pragmatic way.

Governance?

A dictionary will tell us that governance is "a system or manner of government." Not very useful. A thesaurus will offer synonyms such as supremacy, ascendancy, domination, power, authority, and control. It might be the last if we get it right. It's certainly none of the others.

Paul Harmon usefully suggests that "Governance is the organization of management. It refers to the goals, principles, organization charts that define who can make what decisions, as well as the policies and rules that define or constrain what managers can do."[1]

The ultimate outcome of effective process governance is the proactive, efficient management and continuous improvement of the set of processes (and their subprocesses) by which an organization delivers value to its customers and other stakeholders.

OK, so that's clear enough and we probably all agree with this aspiration in the abstract. How do we make it real?

Key elements of process governance

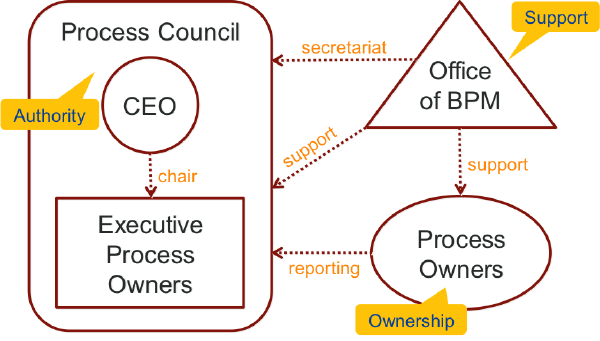

Let's start with a high-level model — the tripartite model shown in Figure 1. This is the model that has developed over my years of projects. It's a generic model to be tailored to suit individual organizations and their environments; the components don't change but the names often do.

Figure 1. Process governance model

There are three themes in the model, three elements that are necessary for effective process governance: authority, ownership, and support.

Process owners are the linchpin as they are the voice of the process. They take ownership of the need to respond to the process performance measurement.

The Process Council is the source of whole-of-organization authority and the place to which process owners can escalate concerns and ideas.

The Office of BPM (aka Process Office, BPM Group, Center of Excellence, Center of Expertise, etc.) provides support to the process owners, the council, and all stakeholders.

There are five important activities that are key to delivering effective process governance: performance management, idea management, anomaly management, improvement management, and model management.

Performance management is about setting performance KPIs and targets, designing the measurement methods, and analyzing and reporting the results.

Idea management is the discovery of process innovation ideas, and although often overlooked or separated, it is a key part of process management.

Anomaly management identifies current or emergent process performance problems and initiates appropriate analysis and corrective action.

Improvement management ensures that the benefits promised from problem resolution or the implementation of new ideas are realized.

Model management ensures that process models and other documentation is of high quality and compliant with modelling conventions and standards.

The Process Council, Process Owners, and the Office of BPM all have an important role to play in the proper and timely completion of these activities.

Process Owner

This is the key role in effective process management; it can also be the most difficult to make work. However, it doesn't need to be like that if the role is clearly defined, the scope properly targeted, and the authority boundaries made clear.

Process owner role

This role is often glibly, and wrongly, defined as being responsible for the performance of the process. For a high-level cross-functional process, the process owner may own (i.e., be the functional manager of) the business unit that executes part of the process, but never all of it — that's what we mean by "cross-functional."

Organizations should not ask anyone to be "responsible" for something over which they have, at best, partial control and, therefore, whose performance they cannot control. Who'd want that role?

I suggest this much better (i.e., honest, accurate, and practical) role definition: A process owner is accountable for responding when process performance is outside the accepted range or trending in that direction, when a change of KPI or target is appropriate, or a new execution idea (innovation) should be tested. That's a role that can be safely accepted — and it is very much a part-time role.

If you ask people to do an impossible job, they will fail.

Process owner scope

An organization has hundreds, or even thousands, of business processes, depending on how deep you go in the process hierarchy. Clearly, you can't have a different process owner for each process.

The good news is that most processes do not need a process owner for two main reasons. Firstly, a process owner is the owner not just of the immediate process but also of its sub-processes. Secondly, most organizations can select a subset of high-impact processes requiring active process management.

Just as we don't need to model all our processes, neither do we need to actively manage them all.

Process owner authority

There are two main approaches to defining the authority of a process owner.

The role may be the design authority for the process, with every process change requiring process owner prior approval. This can create unproductive conflicts between process owners and functional managers — who's in charge here?

Alternatively, the process owner can have no authority at all — a position of influence rather than authority. In this scenario the process owner's job is to monitor process performance and ideas for change and to bring problems and opportunities to the attention of the functional managers executing the process and sub-processes. If the right people are not listening, the process owner can escalate to the Process Council. No more arguments about who is in charge.

I prefer the second scenario where the process owner has no authority. No. Authority. At. All.

Office of BPM

The Office of BPM (OBPM) is the central support service for process owners, the Process Council, and everyone involved in process management and improvement activities.

Process owners and council members must be supported. It is very likely that people newly appointed to these roles will need training and coaching. Process-based management requires a different mindset. It should not be assumed that process owners and councilors arrive fully formed.

It is not the role of the OBPM to do all the process work for the organization. If that is the case, and they are successful, they soon become a bottleneck; they become the OPPI, i.e., the Office for the Prevention of Process Improvement!

The OBPM has two main ways in which it enables good process governance: (1) it provides specific support to the Process Council and process owners, and (2) it raises the process management and improvement capabilities of everyone throughout the organization.

The Office of BPM is a life support system for process-based management.

Process Council

The Process Council provides whole-of-organization coordination and oversight of all process-based management activities and outcomes. For process-based management to be successful and sustained, the organization must make the mandate of process governance clear and support the practical exercise of that mandate. This is the council's role.

Preferably set up as a separate committee, rather than an additional agenda item for an existing committee, the Process Council has these key objectives:

- Ensure process work remains correctly aligned with organizational strategy

- Develop policies related to process-based management and improvement

- Oversee all process management and improvement development activities

- Assess process performance outcomes

- Resolve high-level misalignments or conflicts

Although not involved in the details of implementation, the Process Council is the ultimate authority for all process-related work throughout the organization.

Achieving process governance

The key steps in designing and delivering effective process governance are summarized below. The steps are easier to write down than to complete. However, effective process governance is what makes process-based management possible.

- Create an Office of BPM (or effective equivalent) to support all involved in process work.

- Convene a process council to provide whole-of-organization guidance.

- Create, communicate, and agree on a vision for effective process governance.

- Generate and sustain urgency around the compelling reasons for process governance.

- Clearly define and communicate the process owner role.

- Identify the highest-level processes in a hierarchical process architecture.

- Assign process owners to processes to be actively managed — start with just a few.

- Agree on what good process performance means and how it will be tracked.

- Design and implement process performance reporting systems.

- Support process owners and the council with training, coaching, and timely information.

- Collect, analyze, and report process performance outcomes.

- Based on hard evidence, intervene to correct performance anomalies or test new ideas.

The 7 deadly sins

Implementing and sustaining process governance is difficult, albeit worthwhile. It will be impossible unless active attention is paid to these seven conditions that inevitably lead to failure.

Uncertainty. Ambiguity about the difference between process and functional management can only result in confusion about the purpose of process governance.

Mired in the Minutiae. Process owners who are overly distracted by the details of process analysis, measurement, and management lose sight of their leadership and strategic goals.

Center of Governance. Having an Office of BPM is NOT the same as effective process governance — it is a necessary but not sufficient element.

Goal confusion. Simply running ad hoc process improvement projects as problems surface and solutions are required is not process-based management.

Setting Up to Fail. Appointing process owners from levels too low in the functional hierarchy creates an environment where they can only fail.

DIY. Process owners need organizational support, especially from the Office of BPM and the Process Council. DIY will not work.

Fading out. To really waste a lot of time and money, allow the organization to get excited about process governance for a while and then let support for process owners and the council fade out.

Mind the gap

Borrowing from the railway tradition, process governance is about 'minding the gap'. The 'gap' is the thoughtfully-discovered difference between what the performance of a process should be, or could be, and what it is. The 'minding' is the proactive identification of these gaps, and evidence-based decisions about which gaps need to be closed and when.

When you mind the gap on the process journey, you are consciously and systemically finding and resolving process performance anomalies and opportunities. This is process governance.

References

[1] Harmon, P. 2008. Process Governance. BPTrends Advisor, Volume 6, Number 3. http://bit.ly/bpt_advisor_harmon_governance

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules