ConceptSpeak™ (2): Special-Purpose Elements of Structure for Concept Models

Speaking the Language of the Business with Concept Models

A concept model comprises a set of concepts and the structural relations between those concepts. ConceptSpeak™ is a comprehensive and carefully-coordinated set of guidelines and techniques for designing a concept model.[1] The conventions of ConceptSpeak follow the Object Management Group's (OMG's) Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules (SBVR).[2] In this in-depth series, Ron Ross presents ConceptSpeak's highly-disciplined approach for creating concept models based on well-defined elements of structure.

To express a rich variety of business communications at scale (including but by no means limited to business rules) you need both nouns and verbs. When you compose the business' noun concepts and verb concepts as a coordinated set, the result is a structured business vocabulary (or concept model). A concept model diagram can be used to convey this vocabulary in a visual way that is easily understood by all stakeholders.

As introduced last time,[3] a concept model is more than a collection of business concepts — a concept model also comprises a set of structural relations between those concepts. These elements of structure come in two basic varieties, standard relations and verb concepts. The next part of this series will discuss verb concepts. This discussion covers the four most-important kinds of pre-defined standard relations:

- categorization

- property

- composition (whole-part)

- classification

These special-purpose connections between noun concepts come in handy, pre-defined semantic constructs, as provided by ConceptSpeak™ (summarized in Table 1). Because they come as built-in patterns they are ready to use, thereby significantly extending the reach and precision of the concept model. And because they are standardized they bring deeper meaning to a set of concepts that can be reasoned over.

Before I get too deeply into this, however, I should give a quick note about the terms instance and property.

About the Terms Instance and Property

At this point in the discussion, I will start taking a few liberties with the SBVR concepts of instance and property. In SBVR, instances and properties are always in the real world, not in a model. For example, you can't put the real country Canada into a model (way too big!) In a concept model, you can include only concepts (like the one that stands for Canada). Similarly, my car — the real one parked in my carport — is red. But I can't put its real redness property in the concept model. All I can do is include a signifier (r-e-d) for the concept of redness.

Table 1. Special-Purpose Elements of Structure. Special-Purpose Element of Structure

Pre-defined

FormExample

Use in a Sample Business Rule Statement

categorization

(concept 1) is a category of (concept 2)

'corporate customer' is a category of 'customer'

A customer is always considered corporate if the customer is not an individual person.

property

(thing 1) has

(thing 2)order has date taken

order has date promisedAn order's date promised must be at least 24 hours after the order's date taken.

composition

(whole-part

structure)(whole) is composed of (parts)

(part) is included in (whole)chair is composed of:

- leg

- seat

- back

- armrest

A chair always has a seat.

classification

(instance) is classified as a (concept)

Canada is classified as a country

Canadian Dollar is classified as a currencyAn order may be priced using the Canadian Dollar only if the customer placing the order is located in Canada.

1. Category and Categorization

A category is a class of things whose meaning is more restrictive than, but otherwise compliant with, some other class of things. For example, male is a category of animal. Each male is always an animal, but not every animal is a male. A male can have properties that would not apply to any animal that is not a male. In general, a category represents a kind, or specialization, within a more general concept. Defining one class of things to be a category of another class of things is called categorization.

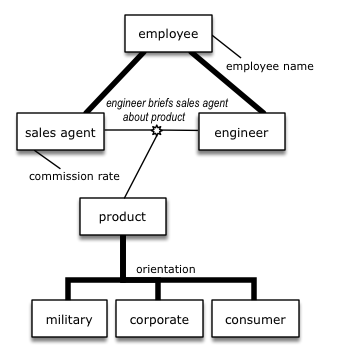

Figure 1 illustrates categorization applied to two general concepts, resulting in additional, more specialized concepts.

Figure 1. Categorization and resulting categories on a concept model diagram.

Note on ConceptSpeak™ Notation

Categorization is represented in a concept model diagram as thick-line connectors between concepts, with the more general concept at the top, and the category(s) beneath. This creates a visual hierarchy, with concepts becoming more specialized going 'down' the hierarchy.

The three-category group for 'product' is organized on the basis of a categorization scheme named orientation — more about that later. If a name is given to the scheme, it is annotated adjacent to the heavy horizontal line (as illustrated in Figure 1).

- Employee has two categories — sales agent and engineer.

I'll get to properties next but, for now, note that employee name (a property) is indicated for employee. Since all sales agents and engineers can have names — indeed, any employee can —name is indicated only for employee. Remember that all sales agents and engineers are employees in this business, so the name property pertains as a matter of course to both agent and engineer. It does not need to be re-specified for them; the applicability of the property to them is assumed. On the other hand, commission rates apparently pertain only to sales agents — not to all employees (e.g., not to engineers) — since commission rate is indicated only for sales agent.

- Product has three categories — military, corporate, and consumer — forming a group.

Note that (as always for categories) military, corporate, and consumer must be products. Indeed, unless everyone reading the diagram is thoroughly familiar with categorization, better labels would be military product, corporate product, and consumer product. The boxes represent that anyway, but these revised terms would emphasize the point.

Any category can have categories; any category of a category can have categories, and so on. Multiple levels of categorization are not uncommon in concept models. Indeed, such refinement or narrowing of meaning as you go 'deeper' yields a high degree of precision or selectivity for making statements about the business. For example, a business rule might be expressed for software engineers, a potential category of engineer, which does not apply either to other kinds of engineers or to employees in general.

How is a categorization shown using a heavy dark line in a concept model diagram recorded in a glossary? No explicit entry need be made for this kind of standard relation. Rather, the concepts are carefully tied together by their meaning. For example [from OED] the definition of 'software engineer' would be written as: an engineer who designs, develops, and maintains computer software.

Here is the crucial observation about this definition: The first noun in the definition is 'engineer'. This usage is absolutely deliberate! It specifies that any software engineer is an engineer, just a special kind or variation thereof. In other words, by forming the definition in this way you are indicating explicitly that a software engineer is a category of engineer.

Categorization is a very powerful notion that is fundamental to the reasoning a concept model supports. This discussion here only scratches the surface.[4] There are important questions to ask about a categorization; here are just a few.

- Can an instance of the more general concept exist that is not allocated to any category? (yes, unless explicitly disallowed)

- Can an instance be allocated to more than one category under the same categorization scheme? (yes, unless explicitly disallowed)

- Can a concept be categorized in multiple dimensions? i.e., have multiple categorization schemes? (yes)

- Can a category have more than one more general concept? (yes, but rare)

To explicitly disallow something, of course, means writing some business rule(s).

Finally, ask yourself this: Have I over-generalized? (And how do I know?) Don't get carried away with all the possible categorization hierarchies you can imagine. Include only what is useful and productive for concise business communications, nothing more.

2. Property

The Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary defines 'property' as a quality or trait belonging to a person or thing. Figure 1 indicates employee name to be a property of employee and commission rate to be a property of sales agent.

The default wording for a property connection is (thing1) has (thing2). The important word here is has. In English, the verb to have is very general — not specific or descriptive at all — and often acts as a catch-all that obscures precise meaning. Best to avoid using it as a verb in your concept model except for property connections.

For properties, has is a very convenient default. In fact, when the verb has is used, the preposition 'of' (shorthand for 'is of') is implicitly available for expressing the reverse direction of the connection. This means you now have the preposition 'of' to use in business communications regarding that property. For example, while you can say "… the commission rate that the sales agent has …", now insteaad you can say "… the commission rate of the sales agent…." This usage permits business statements in a very concise, natural form of expression.

Orientation, which can be seen in Figure 1 just above the crossbar for product's group of categories, is also a property, albeit a special kind. Orientation is the name of the categorization scheme used to organize the three kinds of product. Since orientation is a property of product, you can say product has orientation.

Is it required that every product fall into at least one of the three categories: military, government, or consumer? In other words, must every product have an orientation? (Or perhaps exactly one?) Never assume so — that would require some explicit business rule(s).

A property connection for a concept does not indicate that every instance of that concept actually has an instance of the property, only that it can. If each instance of a concept is required to have an instance of the property, an explicit business rule is required, e.g., An employee must have an employee name.

Note on ConceptSpeak™ Notation

In a concept model diagram, a thin line is used to attach a property to the appropriate box (noun concept). Exactly what does the thin line represent? An unlabeled thin line is simply shorthand for the verb 'has'.

Why bother with a graphical shorthand for properties? The answer has to do with scaling up. If you were to treat all properties as binary verb concepts labeled 'has', the concept model diagram would become hopelessly cluttered with boxes and connections having to do with such things as numbers, names, dates, units of measure, and much more. This kind of visual detail is of secondary importance to the business. Avoid that!

3. Composition — Whole-Part (Partitive) Structure

Things are often composed of other things; that is, they are compositions of distinguishable parts. For example, an automobile (simplistically) is composed of an engine, a body, and wheels. A mechanical pencil is made up of a barrel, a lead-advance mechanism, pencil lead, and eraser.[5] An address (simplistically) includes a street number, a street, an apartment number, a city, a state/province, a zip code/postal code, and a country.

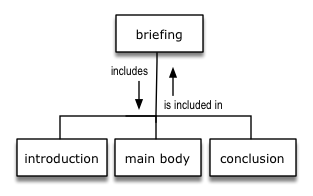

Sorting out the terminology and composition of such whole–part structures is often quite useful. In a concept model a whole-part concept structure is a collection of one or more binary verb concepts that jointly represent how one kind of thing (the whole) includes (typically) two or more other kinds of things (the parts). Such a composition can be represented in a concept model diagram as in Figure 2.

Figure 2 illustrates the composition of briefing using a tree structure of thin lines to indicate its parts: the introduction (tell 'em what you're gonna tell 'em), the main body (tell 'em), and the conclusion (tell 'em what you told 'em).

Figure 2. Concept model diagram showing a composition (whole-part structure).

Note on ConceptSpeak™ Notation

This diagram of a whole-part concept structure features briefing (the whole) as the top box. Connected beneath it are each of a briefing's three main parts. The lines represent verb concepts, each worded includes. The three lines are unified under briefing, then branch to the separate parts forming a hierarchy.

Note that this hierarchy is not a categorization — instances of the three parts are not also instances per se of the whole. So, thin lines representing verb concepts are shown, rather than the heavy dark lines of categorization.

Let's address some relevant questions that need to be considered when fully fleshing out the meaning of a composition structure.

- Can a part itself be a whole composed of other parts? Yes. Multiple levels of composition are possible. For example, the engine of an automobile is itself a composite of many parts.

- Can both a whole and its parts be selectively involved in verb concepts other than the ones forming the whole-part concept

structure? Yes. Example for automobile (the whole):

• automobile is cleaned by service

Examples for selected parts:

• engine is sourced from manufacturer

• body is painted color - Can a whole include only one kind of part? Yes. For example, it might be useful to consider the lone verb concept continent includes country to be a whole-part concept structure.

- Can an instance of a whole not include any instance of one of its parts? Yes (unless some rule disallows it). For example, not every address has an apartment number.

- Can an instance of a whole have more than one instance of one of its parts? Yes (unless some rule disallows it). For example, a chair must have at least three legs (or maybe four, depending on your definitional criteria).

- Can an instance of a part exist independently from an instance of the whole? Yes (unless some rule disallows it). For example, a transmission can be removed from an automobile, stocked in a parts warehouse, then sold for installation into another automobile.

- Can an instance of a part be included in more than one instance of a whole at the same time? Yes (unless some rule disallows it). For example, a power source can be included as a part in more than one circuit.

4. Classification

Classification is actually a very simple idea. It means that a particular thing is enough like some other things that it can be put in the same conceptual bucket with them. For example, Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, and Marie Curie can all be classified as scientists. Grouping things mentally this way is second nature to humans (but not to machines).

A general noun concept classifies potentially many things on the basis of common properties. If a thing possesses all the common properties, it is placed within the conceptual bucket. If the thing doesn't, it isn't.

How do you know what these common properties need to be? You go by the concept's definitional criteria — its definition and definitional rules. Without definitional criteria, a name for a conceptual bucket is just a word. A box with a label on a diagram is just a box. Definitional criteria are the critical element. Let's say the following is the definition given for 'scientist': person engaging in a systematic activity to acquire knowledge that describes and predicts the natural world. Is this a fit for Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, and Marie Curie? Yes. So, each can be classified as 'scientist'.

An instance is any of the things a concept corresponds to — anything that lands in that conceptual bucket. Some concepts have a great many instances. For example, a company might take thousands or millions of orders. The instances of some general concepts are actually infinite — for example, number.

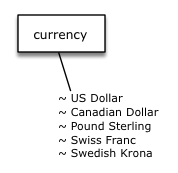

For most concepts, the instances are not known in advance and are too numerous to be included in a concept model. Sometimes, however, you do want to record the names of selected instances, especially for those concepts where the instances are prescribed in advance and relatively stable. For example, the names of currencies the business deals in. Moreover, the business will need to pre-define instances when it has some business rule(s) that pertain selectively to them — for example: An order may be priced using the Canadian Dollar only if the customer placing the order is located in Canada.

Making the connection between an instance and its particular general concept is called classification. Figure 3 illustrates.

Figure 3. Concept model diagram showing classification.

Note on ConceptSpeak™ Notation

In a concept model diagram, an instance preceded by the wavy-bullet symbol (tilde) indicates a classification connection from the instance (e.g., US Dollar) to its general concept (here, currency).[6]

Showing examples on a diagram can be an effective way to display and discuss them, often leading to a better understanding of what is meant by the concept. As a practical matter you will represent only a relatively small subset of all instances in a concept model diagram. To avoid clutter, we recommend ample use of neighborhoods[7] to depict instance-level terminology that is used in business communications.

References / Notes

[1] Extracted from Business Knowledge Blueprints: Enabling Your Data to Speak the Language of the Business, by Ronald G. Ross, 2020.

http://brsolutions.com/business-knowledge-blueprints.html![]()

[2] Refer to the SBVR Insider section of BRCommunity.com for more information about SBVR. SBVR was initially published in January 2008 by the Object Management Group (OMG). Its central goal is to enable the full semantics of business communication (including business rules) to be captured, encoded, analyzed for anomalies, and transferred

between machines.![]()

[3] Ronald G. Ross , "ConceptSpeak™ (Part 1): Elements of Structure in Concept Models," Business Rules Journal, Vol. 22, No. 1, (Jan. 2021)

URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2021/c055.html![]()

[4] Exploration of questions such as these is beyond the scope of this introductory discussion. For in-depth coverage of the many aspects of categorizations, see Chapter 10 "Categorizations" in Business Knowledge Blueprints (op cit).![]()

[5] From [ISO-704] International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Terminology work — Principles and Methods. English ed.:

ISO (2000), p. 9. ![]()

[6] Using a double-wavy hatch mark (tilde) on the connector line to indicate classification is an acceptable alternative graphic convention.![]()

[7] A neighborhood is a page or tab in a large graphical concept model diagram that generally concentrates on categories, properties, and instances for just one or several core concepts.![]()

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules