Active Process Management in 9 Question

Active process management? Isn't that an oxymoron? Can you do inactive process management? Yes, you can, and too many organizations do exactly that. With the best of intentions, they mean to manage processes but end up drawing, modeling, maybe measuring, sometimes improving, but at best it's episodic and problem driven. It's not systemic. It's not performance driven. It's not active; it's reactive.

We can do better. Let's get active.

Nine questions provide a useful framework and guardrails for effective and active process-based management.

9 Questions

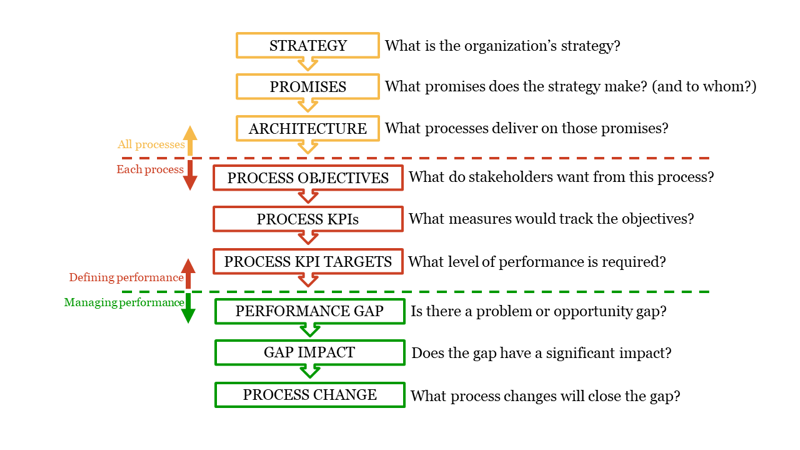

The nine questions can be seen in Figure 1. Each will be discussed in turn below but first a review of the overall diagram which provides an overview of effective and sustained process-based management focused on performance optimization.

The purpose of process-based management is to enable effective and sustained improvement of the right processes at the right time with optimum organizational performance impact.

Figure 1. Active Process Management

Start at the bottom (green section) of Figure 1. This layer is about managing performance. We identify a performance gap caused by a problem or opportunity, assess its impact, and if we decide the gap is worth closing, we do so. At that level we are managing process performance. That implies that we know which process to improve and what good performance looks like.

Move up to the middle (red) layer where we define performance targets. The essential question (indeed, the most important question in the entire process universe) here is "If all the key stakeholders were happy with the performance of this process what would it be doing and how would we know?" Answers to that question define the performance of the process in focus. But which process?

In the top level of Figure 1 we create the structure that will enable discovery of all business processes, the process architecture (aka enterprise process architecture or business process architecture). The two lower layers deal with one process at a time. Here in the top layer, we want to create a structure that will enable us to identify all processes so we can make wise, evidence-based choices about which ones to improve for maximum organizational performance impact.

Implementation of process-based management starts at the top of Figure 1 and works down. The nine questions are discussed below in that order.

Strategy

What is the organization's strategy?

In every organization, strategy is executed via cross-functional business processes. So, active process management must start with, and always reflect, strategy. Whatever format the strategy documentation takes — vision/mission, purpose, values, mandate, etc. — it provides the starting point for developing the process architecture.

Pro tip: You can't process-manage your way out of an inadequate organizational strategy. Poorly-developed and/or poorly-explained strategy is a fatal weakness.

Promises

What promises does the strategy make? (And to whom?)

Organizational strategies make promises to stakeholders. These promises, or value propositions, define why the organization exists. To begin the translation of the strategy into a practical framework for operational execution, search through the strategy and discover what promises are made and to whom.

Pro tip: Search through the vision/mission (or other statements) looking for and highlighting the verbs that will likely point to promises made.

Architecture

What processes deliver on those promises?

Translation of the organizational strategy into pairings of value (products, services, or experiences) delivered to stakeholder cohorts, indicates the highest-level processes that deliver on those processes. For example, one high-level process for a hospital might be Care for patients; for a university Produce graduate; for a government regulator Motivate the market and Empower users.

Pro tip: In the initial development of a process architecture, discover the first three levels (top down from the strategy) as a sound base for ongoing development and improvement. Be clear how the process architecture can be changed efficiently and effectively since continuous improvement requires continuous (well-controlled) change.

Objectives

What do stakeholders want from this process?

Now that we have an overall process architecture structure, we look at processes individually. What is this process supposed to achieve? The people to ask are the process stakeholders, those that give something to and/or get something from the process. Stakeholders decide what good performance looks like and can best explain the impact of substandard performance. The challenge is then to synthesize a single set of objectives for the one process and resolve any conflicting requirements amongst stakeholders.

Pro tip: Conflicting requirements amongst stakeholders, e.g., one wants the process to be faster and another wants it to be slower, probably means that there are two process variants, effectively two different processes. An example might be the very different treatment of requests from premium customers (e.g., frequent flyer program members) and ad hoc customers.

KPIs

What measures would track the objectives?

A clear and shared understanding of the performance objectives of the process allows for the discovery of the critical few process KPIs that will define its performance in more specific detail. These are KPIs created for the process, not just selected from some other list of functional KPIs. If this process were working as well as its stakeholders want it to, what would it be doing and how would we know?

Pro tip: While there is no formula or definitive number, we always want the smallest viable set of process KPIs. Useful challenge questions: If we could just measure three things, what would they be? What if we could measure just one thing?

Targets

What level of performance is required?

KPIs without targets are just aspirations. Further consultation with stakeholders and others is necessary to establish both what is possible and what is required, and how we reconcile the two. If we have decided that the KPI is Ontime Delivery, what is the target? We might decide something like 98% of transactions should be completed within the promised time. Can't stop there, we need a lot more detail. Where is that data going to come from? How can we know if the process was executed on time? What is the "promised time" — a fixed time for all transactions, or perhaps variable for each?

Pro tip: The KPI target may not be a simple, single number. Keep it as simple as possible, but a KPI target could be a matrix of numbers. For example, we might set different levels of performance for different customer types or different products/services. The matrix of KPI targets might even be multi-dimensional, for example, or there might be different targets for multiple services across a variety of customer types in different times of the business cycle.

Gaps

Is there a problem or opportunity gap?

Continuous improvement requires continually searching for an opportunity to improve a current or emergent problem to fix. Creation of process KPIs and targets means nothing if we aren't actively using them. A lot of process improvement work, and the language we use to describe it, is focused on problem resolution. While this is obviously important, it is equally important to be also searching for new ideas. Just because a process is achieving all its performance targets, doesn't mean that it can't be cost-effectively improved. We need to actively search for, and find, performance gaps driven by both performance data and innovative ideas. Continuous problem finding doesn't sound as attractive as continuous improvement, but you can't have one without the other.

Pro tip: Effective process improvement requires a systemic ability to find process performance gaps. Such gaps might be performance-driven or idea-driven, i.e., about fixing problems (current or emergent) or capitalizing on ideas.

Impact

Does the gap have a significant impact?

Every organization could define thousands of processes — tens of thousands if you go a little deeper. Many of those could be improved in some way. We can't work on them all and must make wise choices about prioritizing effort and investment. Rigorous impact analysis is too often missing in process improvement projects. What is the real-world impact of making, or not making, a change to a process? What is the urgency of doing it now?

Pro tip: Without a strong positive business case for a process change with real commitment from the business units involved, change will not happen, no matter how well the process improvement project did the analysis and how solid were their recommendations.

Change

What process changes will close the gap?

And finally, we arrive at the purpose of the whole exercise. Process management and improvement is about delivering proven, valued, business benefits (PVBB) — benefits for the business, valued by the business, and proven through objective, credible data about which there is no dispute. If process-based management is not delivering PVBB then, by its own definitions, it is waste to be eliminated. It's a tough standard, and it must be applied.

Pro tip: The process of process improvement must also be managed. Indeed, we might argue that it should be the best-performing process. One of its process KPIs should be about the percentage of process-change projects implemented as planned, and the target should be at least 90%.

Active Process Management

The purpose of process management is to improve the quality of process improvement through a systemic, targeted approach.

The purpose of process improvement is to optimize an organization's performance in the execution of its strategic intent.

This requires the development of deep understanding of the high-impact processes that enhance or handicap organizational success.

This requires active process management.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules