The Two Fundamental Kinds of Rules

Extracted from Rules: Shaping Behavior and Knowledge, by Ronald G. Ross, 2023, 274 pp, https://www.brsolutions.com/rules-shaping-behavior-and-knowledge-book.html

Rules often pertain directly to behavior. No Shirt, No Service. Such rules are called behavioral rules. The world abounds in such rules; business and society are based on them.

Rules can also relate indirectly to behavior, by helping to shape the understanding on which behavior is based. For example, what's a 'shirt'? Does an undershirt count? How about a tank top? A bikini top? Does a shirt have to cover the shoulders? Definitional rules provide criteria to answer such questions.

Behavioral rules and definitional rules are fundamentally different, a fact having profound consequences for business, analysis, and software platforms. Specifically, behavioral rules can be violated (by people, organizations, or software acting in their behalf) — definitional rules can't be violated, ever.

Another difference is that, unlike definitional rules, behavioral rules confer rights in groups and communities of people. Rights are hardly a trivial matter, not least where contracts and agreements are involved.

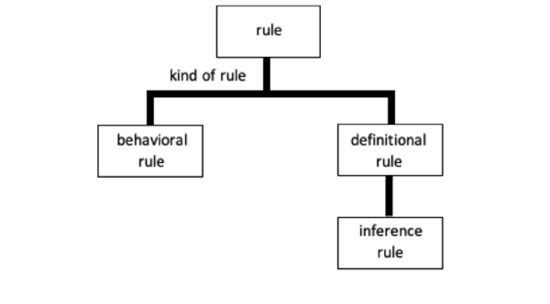

Figure 1 represents the two kinds of rules. The heavy dark lines indicate categories.

Figure 1. The Two Fundamental Kinds of Rules

Inference rule is shown as a special category of definitional rule. Perhaps it seems a bit lonely there under definitional rule. Appearances are deceiving. There's a rich panoply of guidance associated with behavioral rules, but it's beyond the scope of this discussion.

Behavioral Rules vs. Definitional Rules

Think Thou Shalt Not Kill. Society has police forces, judicial systems, prisons, and much more, all because such behavioral rules can be violated. Seeking out and responding to violations of these rules is the very essence of compliance.

Definitional rules, in contrast, might be misunderstood, misinterpreted, or misapplied but can never be violated. Definitional rules simply shape knowledge about the world; certain concepts (e.g., 'shirt') simply are what they are by definition. There is no choice in the matter. (Since there is no choice in the matter, the word 'should' is inappropriate for expressing definitional rules.)

For example, if you let someone into a restaurant wearing a ragged undershirt, you didn't violate the (definitional) What's-a-Shirt Rule(s), you violated the (behavioral) No-Shirt, No-Service Rule. You merely forgot about or misunderstood the What's-a-Shirt Rule(s). (Sample rule later.) Behavioral rules, not definitional rules, are where the rubber meets the road in human activity.

What are definitional rules for? Definitional rules supplement definitions. (More later on exactly how.) Definitional rules literally tell you what counts as an instance of a concept and what doesn't. For some concepts they can be numerous and complex. Examples:

- Does a case of self-defense count as a murder?

- Does a prospect count as a customer?

- Does a subsidiary's customer count toward a company's market share?

Certainly, you can have behavioral rules without definitional rules, but such behavioral rules are likely to prove less than effective. To say that differently, behavioral rules without definitional rules are often vague. Lack of precision means enforcement will be inconsistent or capricious.

How do you determine whether a rule is behavioral or definitional? Ask whether or not it always has to be true by definition. For example:

Rule: A customer is to be assigned an agent if the customer has placed an order.

Is there anything in the definitions of customer, agent, or order that requires this rule to be true in all circumstances (in logic, all possible worlds)? The answer is probably no. So, this is a behavioral rule. It can be broken.

More About Behavioral Rules

Behavioral rules aim to directly shape people's behavior (even when embedded in manual procedures, represented by software, or enforced by bots). Just like rules for your children, they set boundaries for acceptable behavior.

Some boundaries are meant to be hard ones: Never run into the street without looking. Other boundaries are meant to be soft ones: Never pull the dog's tail. In other words, strict adherence to some behavioral rules is expected; others serve just as guidelines.

In business, it's quite important to know which is which. Enforcement or sanction for violating 'hard' rules should be stringent; for 'soft' rules, enforcement and sanction can be relatively mild or even non-existent. Nonetheless, it's important to recognize that guidelines are rules too. All behavior-shaping rules should rest on the same footing so they can be collectively marshalled to greatest effect.

Because of the direct implications for people's activity in going about their activity, behavioral rules carry the sense of obligation or prohibition. Behavioral rules indicate what:

- must or must not be

- ought or ought not be

- should or should not be

The key thing to remember about behavioral rules is that they can be violated. Their intent is to shape or constrain the actions and activity of people and organizations (actors with agency).

Aside: Such actions or activity do not include CRUD (create, retrieve, update, delete) events per se. Those are merely events in a record-keeping (data) system, not the real world of actors with agency. On the other hand, suppose an outside organization supplies your organization with data. That action is subject to behavioral rules because two actors with agency are involved.

Consider the following rule:

Warehouse Access Rule: A gold customer must be given access to the warehouse.

If a gold customer is denied access to the warehouse, then a violation has occurred. Presumably, some sanction is associated with such violation — for example, a security guard might be called on the carpet.

Aside: It is not possible or even desirable to name every rule. Rules here are named to provide easy reference for discussion.

Since behavioral rules can be broken, their analysis needs to carefully focus on the potential for violations. You need to become violations-aware.

For the same reason, behavioral rules also require special care in reasoning (automated or otherwise). Consider the Warehouse Access Rule for example. It cannot be assumed that the rule has always been faithfully enforced; therefore, it cannot be inferred that in every situation where it was appropriate for a gold customer to be allowed access to the warehouse, the customer actually was allowed such access. Violations happen!

Aside: By 'reasoning' I mean evaluating rules to logically infer factual conclusions from other facts.

Many behavioral rules are automatable. Here are some examples:

- An order over $1,000 must not be accepted on credit without a credit check.

- A high-risk customer must not place a rush order.

- An order's date promised must be at least 24 hours after the order's date taken.

Some behavioral rules are not automatable, at least not directly using current technology (e.g., No elbows on the table.). Non-automatable behavioral rules require special attention to detecting potential and actual violations, and to enforcing consequences.

Technology is moving forward, of course, at breakneck speed. Behavioral rules formerly considered non-automatable are falling like dominos to bots and special surveillance measures. Consider the Warehouse Access Rule. Would it be feasible to use facial recognition software to admit gold customers to the warehouse while rejecting others?

More About Definitional Rules

Definitional rules also shape people's behavior, but only indirectly. Instead of behavior, they shape the concepts on which behavior is based.

Wait a second, isn't the purpose of definitions to shape concepts? Yes. The problem, however, is that definitions usually leave too much wiggle room for business purposes (and reasoning). Consider this definition of shirt[1]:

Definition of Shirt: a garment for the upper part of the body, as a loose cloth garment usually having a collar, sleeves, a front opening, and a tail long enough to be tucked inside the waistband of trousers or a skirt

"Garment for the upper part of the body" is vague (how much of the upper body?); the word "usually" isn't helpful at all (specifically when?!). The definition leaves many other unanswered questions, such as whether a shirt absolutely has to have:

- a collar. (If so, t-shirts are excluded.)

- sleeves. (If so, muscle shirts are excluded.)

- a tail long enough to be tucked inside the waistband of trousers or a skirt. (If so, crop tops are excluded.)

Without some definitional rule(s) to close these gaps, who knows how the (behavioral) No-Shirt, No-Service Rule will be enforced in practice!

Let's suppose the restaurant does intend a shirt to have sleeves and a long 'tail,' but not necessarily a collar. If so, the following definitional rule needs to be specified explicitly in addition to the concept's definition:

What's-a-Shirt Rule: A shirt has sleeves and a tail long enough to be tucked inside the waistband of trousers or a skirt.

Instead of defining a separate rule for these conditions, could the definition itself just have been modified? Yes. Is that always practical? No. Consider how many specific criteria might be involved for concepts such as:

- murder

- money-back guarantee

- supplemental income

Definitional rules are useful where a higher degree of precision is needed than basic definitions provide because of the risks associated with misapplication of some behavioral rule(s).

Sorting out all the extensive criteria to ensure consistent interpretation and application of behavioral rules is the heart of the problem for laws, regulations, contracts, agreements, business policies, and so on. Indeed, it is the heart of the problem for deep knowledge of any subject matter that involves risks. All such specifics usually just don't fit comfortably in definitions.

Because of the direct relationship of definitional rules to definitions, definitional rules carry the sense of necessity or impossibility. Definitional rules indicate what:

- counts and does not count

- has to be or has not to be

The key thing to remember about definitional rules is that they cannot be directly violated.

Let's assume the following for 'gold customer'.

Definition of Gold Customer: a customer that regularly places large orders and merits highest-level service

Gold Customer Rule: A customer is considered a gold customer if the customer places more than 12 large orders during a calendar year that are each fully paid within 60 days.

Now remember the (behavioral) Warehouse Access Rule:

Warehouse Access Rule: A gold customer must be given access to the warehouse.

If a gold customer is denied access to the warehouse, it's not because definitional Gold Customer Rule has been violated; it is because the behavioral Warehouse Access Rule was violated. The former rule can only be misunderstood, misinterpreted, or misapplied.

All definitional rules are potentially automatable. Since definitional rules cannot be broken (unlike behavioral rules), definitional rules can be used directly for reasoning — automated or otherwise.

Aside: To be automatable, a rule must be practicable. Whether an automated definitional rule can be evaluated in real time depends on whether all the relevant facts are available.

Definitional rules are basic to asking for counts of things. Getting counts right does require some awareness of time. For example, if you had asked in 2005 how many planets our solar system has, the answer would be 9. As of this writing, the answer would be 8. Definitional rules can change over time. Poor Pluto!

References

[1] Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary: (1) and (1a).

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules