Being Violation-Aware: Five Questions for Behavioral Rules

Extracted from Rules: Shaping Behavior and Knowledge, by Ronald G. Ross, 2023, 274 pp, https://www.brsolutions.com/rules-shaping-behavior-and-knowledge-book.html

The key feature of rules for groups and communities of people is that individuals and organizations (and machines) will sometimes break the rules.

It's obvious. It happens all the time. Just look around you. Think about how much time and energy we spend trying to anticipate, detect, and sanction violations. That's why we have regulators, police, and prisons. And compliance departments. And endless data cleansing activity.

People and organizations have agency; as actors they have free will. They have flaws, motivations, and insights that sometimes lead them to break the rules. It's up to the authority behind the rules (the body that creates and monitors the rules) to determine which breaches are deadly serious (murder), which are minor (jaywalking), and which are actually innovative ('thinking outside the box').

There's more. Whenever a rule is violated, some party is stepping on some other party's right. Sometimes the transgression is not worth mention; other times the harm is quite significant. To protect such rights, governments make laws and regulations, and parties enter into contracts and agreements.

Our current approaches dance all around the fact that rules can be broken — or ignore it completely. Instead, the fact that rules can be broken should be front and center. We should make the possibility of violations a centerpiece of guidance and analysis. It's the key to being rule-based, and to being a real-time enterprise as well.[1]

Five Violation Questions for Behavioral Rules

Being violations-aware is not as hard as you might think. Once you capture the rules, the patterns are straightforward. All you need to know is what questions to ask and what form the answers can take. Specifications that before may have seemed ill-focused and incomplete now become orderly and explainable.

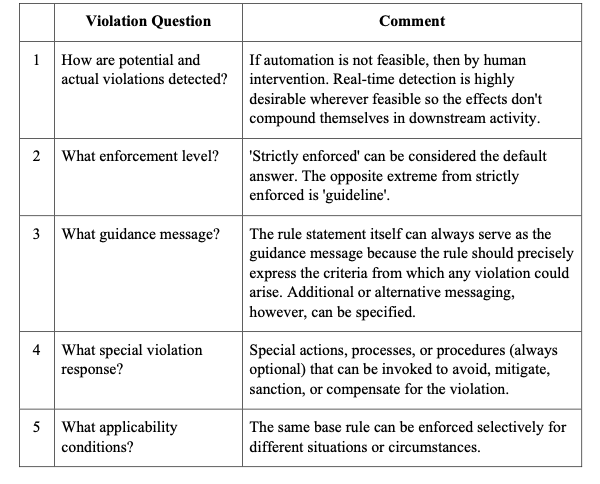

Table 1 lists the five questions you can ask about each behavioral rule and identifies the default answer for each question. Additional explanation and examples are presented below.

Table 1. Questions for Behavioral Rules

Some important points about these questions:

- Since the possibility of violations is the central characteristic of behavioral rules, the questions naturally focus on violations. Detecting and rewarding compliance with behavioral rules, however, might sometimes also be desirable. (Who doesn't like the occasional treat for acting properly, especially when learning?!) Also, the performance of particular actor(s) in complying can be monitored over time.

- How strictly you want a behavioral rule to be enforced (question 2), and what you want to do in response to violations (questions 3–4), are different issues than the logic the rule itself expresses. Separating these concerns is highly empowering.

- Questions 3–5 are optional. They simply expand on your capacity to apply the rules intelligently.

Answers to the questions usually only emerge over time, not when a rule is first drafted. Where special answers are required, iterative walk-throughs of different scenarios always prove helpful.

Most importantly, answers should not be considered static once deployed. They should be easy to change so that reactions to violations can evolve naturally as circumstances warrant. Such capability is key to being rule-based, as well as to true business agility.

Question 1: How Are Potential and Actual Violations Detected?

How to detect violations is the most basic question of all for a behavioral rule. If violations can't be detected, then a rule cannot serve as more than as simply a guideline. That fact doesn't mean the rule isn't important; shaping behavior through education and awareness is by no means a trivial aspect of rules.

Fortunately, many behavioral rules are directly automatable, so detection is more or less a given.

Aside: The "more or less" depends on available platform or software environment. Technical staff may need to analyze how potential violations can be detected using current capabilities.

For those rules that are not directly automatable given available technology, human intervention is required. Responsibility for detecting potential and actual violations must become part of someone's job responsibilities (and training).

Consider a restaurant's No-Shirt, No-Service Rule. Who will be responsible for verifying shirts are being worn by customers? Consider these possibilities:

- The restaurant has seating hosts at the entrance. A relatively straightforward solution is to task those hosts with responsibility for detecting potential violations. A big advantage is real-time enforcement.

- The restaurant is self-seating. Here, the question becomes more difficult. Perhaps responsibility could be given to waiters. Or better, perhaps to a roving manager, in order to separate service from policing.

- The restaurant is self-service (think cafeteria or server machines). Now, the problem potentially becomes very difficult. Apparently, the restaurant was purposely designed to minimize human intervention, so the rule could be colliding with basic business strategy. Perhaps the restaurant could simply rely on the honor system (and the disdainful frowns of fellow customers). Or maybe the rule should simply be discontinued.

In examining these possibilities, did you notice (if not before) that 'service' needs defining? For example, can a customer enter without a shirt if the 'service' is simply to pick up a take-out order?

Aside: A bot at the entrance could probably support automatic shirt recognition. For the average restaurant, of course, this solution might prove too expensive or difficult. And what could the bot safely do about enforcement? Make no mistake, however, bots will increasingly be used for detection of violations where feasible and ethical. Ever get a traffic citation through the mail for late entry into an intersection at a red light? Or using a toll road without the proper windshield tag?

Question 2: What Enforcement Level?

The most distinctive question for a behavioral rule is how strictly it should be enforced. Consider the No-Shirt, No-Service Rule. Assuming the rule is fundamental to the business strategy, it should probably be strictly enforced.

But some discretion might be warranted. Consider the following possibilities.

- The air conditioning is broken and it's quite hot inside.

- A young child barely walking is brought by properly-attired parents.

- The restaurant owner shows up shirtless and wants to dine.

Perhaps the host should be permitted to override the rule in some or all of these circumstances. Allowing for (well-considered) human discretion in the enforcement of rules in appropriate situations is a fundamental need for business and government.

'Guideline' is the least restrictive of all enforcement levels (no sanction of any kind for violation). Essentially a guideline is simply a well-formed suggestion. Still, a guideline should be treated as a rule, not least because its enforcement level might need to be adjusted over time.[2]

Other circumstances can entail different enforcement levels. For example, one of our clients focusing on data quality created a half-dozen shades of 'accept' vs. 'reject' aimed at incoming data from external organizations.

Remember that the enforcement level for any given rule is always completely independent of the logic expressed by that rule. That way, either of them can be changed on its own at any time. This separation supports highly-agile business capabilities.

Question 3: What Guidance Message?

Violations of rules are always potent teaching moments. There is no better way imaginable to dispense knowledge in real time, especially in automated fashion.

Consider the No-Shirt, No-Service Rule. Presumably, the rule is posted visibly at the entrance to the restaurant. When a shirtless person who seeks to dine is turned away, they have been memorably informed of the restaurant's policy.

Of course, such 'education' could prove painful, embarrassing, or even enraging if not softened in some fashion. Preparing the host with some disarming message would probably be prudent — perhaps something like "The owner is pretty old-school. If I let you in without a shirt I could be fired. Just throw on a t-shirt and you'll be fine."

Here's the point. The rule itself always provides the logic behind violations. The No-Shirt, No-Service Rule speaks for itself, just like any other rule should. But sometimes additional messaging is useful or wise. Such messaging can clarify the rule, indicate the rule's motivation, tutor participants, or provide some solution(s).

Two quick additional points:

- We use the term guidance message rather than violation message because rules that are guidelines just support guidance, not enforcement.

- Who sees which guidance messages in what context is always a matter of concern. For example, you probably don't want a trespasser to see your what-to-do-in-case-of-trespassing rules when the trespasser causes a violation. Sensitive rules and other guidance messages should be made available only on a selective, need-to-know basis.

Question 4: What Special Violation Response?

Violation of a rule is often an occasion for selective, on-the-spot remediation. Such responses could be aimed at mitigating risks (think computer hack) or seizing opportunities. Consider the No-Shirt, No-Service Rule.

Rejecting a shirtless customer risks displeasing the customer. How could the restaurant soothe ruffled feathers? Perhaps a discount coupon could be offered as an enticement for a future visit. Does the rejected customer seem unruly? Perhaps a message should be sent silently to the manager.

Instead, the occasion might be viewed as an opportunity. Perhaps the shirtless customer could be offered a low-cost t-shirt to wear emblazoned with the restaurant's logo, name, etc. The customer's business would be salvaged, plus the restaurant gets free advertising when the t-shirt is worn subsequently.

Violation responses always involve some kind of action, which might or might not be automated. They can generally be any of the following:

- processes or procedures (e.g., to assist in fixing the problem)

- posting of penalties or incentives (e.g., a fine)

- special messages or displays (e.g., an alarm, warning light, etc.)

- scheduling an event (e.g., a review to ensure the problem is resolved)

- enforcement of other rules

Aside: The execution of any violation response, as for all actions, takes matters outside the guidance knowledgebase (rulebook). Logically, side effects are unpredictable.

A rule can have multiple violation responses, as warranted. The same violation response can also be shared by multiple rules. Since violation responses are not part of a rule per se, they can be changed independently of the rule(s). They are always optional.

At this point you might be wondering about the 'no-service' part of the No-Shirt, No-Service Rule. Doesn't that phrasing suggest an action of some sort (e.g., deny entrance)? And you are right to ask! What works as a posted message doesn't always work well as a formal statement of guidance.

Question 5: What Applicability Conditions?

Sometimes different enforcement levels, guidance messages, and/or violation responses apply to the very same base rule in different situations or circumstances. Applicability conditions permit highly-nuanced responses to detected violations — that is, situational sensitivity and situational awareness.

Suppose the restaurant decides to relax enforcement of the No-Shirt, No-Service Rule at certain times. Perhaps the clientele at those times is different, a new business opportunity presents itself, or management wants to take some pressure off staff. For example, management might promote the concept of 'grunge lunches' (lax dress code) on Friday and Saturday.

Specifying applicability conditions for the base No-Shirt, No-Service Rule allows differential enforcement to support 'grunge lunches'.

Grunge Lunch Applicability Condition: Lunch time on Friday and Saturday

Enforcement Level: guideline

Business-As-Usual Applicability Condition: All other times

Enforcement Level: strictly enforced

Two more ways in which applicability constraints prove quite useful:

- To provide a special way of handling 'exceptions' (exceptional circumstances) for the very same rule.

- To reduce the overall number of rules to be captured and managed, thereby to help maintain the focus on core guidance.

This second point is especially important. Consider the following example: Suppose a parking rule has a limit of one hour with a grace period of 10 minutes. At the one-hour mark you get a warning (maybe a flashing red light). If not resolved by the 70-minute mark, you get a citation. Those are not two rules. They're just one, with different applicability conditions.

Also, as this parking example suggests, applicability conditions are an important means to escalate reactions to unresolved violations.

References

[1] For more about the two fundamental kinds of rules, refer to "The Two Fundamental Kinds of Rules," Business Rules Journal, Vol. 24, No. 6, (Jun. 2023),

URL: http://www.brcommunity.com/a2023/c120.html

[2] A set of fine-grained enforcement levels suitable for automated real-time activity is suggested in Appendix H of Rules: Shaping Behavior and Knowledge, by Ronald G. Ross, (2023), 274 pp,

URL: https://www.brsolutions.com/rules-shaping-behavior-and-knowledge-book.html

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules