Putting Decisions First Why Building Decision Models Delivers Business Rules Succes

Ron Ross, Roger Burlton, Jan Vanthienen, and I participated in a panel on decisions at the recent Building Business Capability conference. Ron published an article outlining his position[1] recently, and this month it's my turn.

The business decisions your organization makes and, especially, the operational business decisions it makes, are what make your organization smart. Only if you decide to act differently from others, from your competitors, can you be smarter than your competitors. While your strategic and tactical decisions matter, the operational decisions that impact an individual customer, an individual supplier, or an individual transaction are the most central to how "smart" your organization acts and how it is perceived.[2]

In Ron's article[1] he used a nice definition of a business decision that will work just fine for the purposes of this discussion:

a determination requiring operational business know-how or expertise; the resolving of an operational business question by identifying some correct or optimal choice

Business rules are central to these kinds of decisions as they allow us to represent, and execute, much of the business know-how and expertise required to make (and automate) these decisions. Making a single decision may require, among other things, the correct application of many business rules, and it is by enabling us to make correct decisions that business rules add value.

There's a common myth out there that some business rules don't contribute to decision-making — that they relate only to governance. This is not generally true as these rules must be applied if they are to make any difference. An organization has to decide if something violates its policy or the appropriate regulations, and it has to decide on an appropriate response. If the organization has no way to decide that something violates its obligations, or cannot decide what to do when it does, then as far as anyone outside the organization is concerned it might as well not have known what those obligations, those behavioral rules, were.

These operational decisions are largely made when a business process reaches a certain point. Generally the process cannot or should not continue until the decision is made, whether by a person or a system. Decisions are also taken in response to business events. For instance, organizations have to act when someone retires or quits the company or when a new piece of documentation relating to a case is detected. In some situations they always respond to the event the same way, by invoking the same process for instance. But often a decision must be made as to the appropriate response to that event. The business rules that govern the response to that event define the decision that must be made.

Interestingly enough, experience shows that many of the decisions that handle these event responses are also part of a larger decision that is made in a business process. In other words, if one decomposes a business decision that appears in a business process one often finds decisions that also have an independent role in responding to an event. This is why it is critical that the kind of decision model described below is a network, not a hierarchy — reuse of decisions is widespread and important.

Decision modeling is all about capturing and describing the specifics of decisions — particularly repeatable, operational decisions — in a graphical notation and structured format. Decision modeling is best done before business rules are specified in detail and, ideally, in parallel with process modeling. Decision modeling can involve both top-down and bottom-up creation of models. While decision modeling is a new area, there is an increasing amount of information about how to develop Decision Models[3] as well as an emerging industry standard, the Decision Model and Notation (DMN) standard.[4]

In an article of this length I can't get into too many specifics — check out the references if you want more detail — but it's worth noting some of the key elements of a decision model:

- It shows the information required by the decision.

A decision model shows the business entities, the information, that is required by each decision. Showing the input data required by each decision makes it clear what will have to be provided from outside the decision-making context. This input data can and should be mapped to data or fact models that describe this data in more detail.

- It shows the know-how required to make the decision.

A decision model shows the knowledge sources that are the authorities for each decision. These might be expertise, policies, or regulations that explain how to make the decision. They can also be analytic knowledge sources that show how to improve decisions.

- It describes the decision precisely.

Each decision is identified and described, using a Question/Allowed Answer paradigm primarily, and then decomposed or broken down into its components. This decomposition identifies the other decisions — sub-decisions or pre-cursor decisions — that need to be made before this decision can be made. This enables a precise definition of the decision-making when this is required while allowing high-level models to be developed when that level of detail is not appropriate. When complete models are developed for a decision they can also be enhanced with decision logic (in the form of decision tables, for instance) to create a complete and potentially-executable definition.

- It allows for automation boundaries to be managed.

Because the decision is described in appropriate detail, a decision model allows those parts of it that will be automated to be identified. It also allows different phases of automation to be identified.

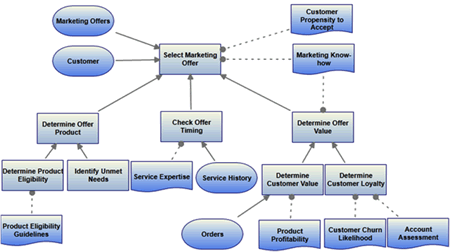

All of this is shown in Figure 1. This diagram uses the Decision Model and Notation style to represent decisions (as rectangles), input data (as ovals), and knowledge sources (as documents). The solid arrows show how decisions require information, either input data or the results of other decisions. The dashed lines show which knowledge sources act as an authority for which decisions.

Figure 1.

Using the Decision Model and Notation style to represent decisions, input data, and knowledge sources.

What's the value of putting decisions first, of identifying and analyzing the decisions in your business or your business process and making them first class objects in your business architecture? In projects with customers we see four key benefits from this focus on decisions first.

Benefit #1: Simpler, Smarter, Agile Processes

Business processes can and do become overly-complex when decision-making gets wrapped up with the rest of the process. If you try to model the logic, the business rules, of your decision-making directly in your business process model then you will add far more gateways than you need or can possibly manage, turning your process into a nasty nest of branching.

If you try to describe decision-making in business processes simply by mapping the business process tasks to business rules, you end up smearing business rules throughout the business process like peanut butter. The business process and the business rules become totally intermingled, making for a maintenance nightmare.

The solution is to explicitly identify a decision as a task in the business process. Managing decisions separately reduces the complexity of your process, and a simpler process is easier to understand and to change, increasing your agility. The decision-making can't be a black box, however, so each decision-making task needs to be described with a decision model. This further increases agility and transparency by making it clear how each decision is made and by making it possible to alter process and decision-making independently.

This approach also results in smarter processes as it allows for greater automation using business rules management systems. Automated decisions mean more straight-through processing. Modeled decisions that are then implemented as business rules mean more right-first-time processing. Finally, decision models make it clear where analytics can play a role in improving decision-making, allowing Big Data analytics to be effectively applied.

Benefit #2: Real-world Business Rules Management

Decisions that appear in business processes often involve hundreds (even thousands) of business rules. Apparently straightforward decisions like "Validate medical claim" or "Check completeness of application" can and do involve large numbers of rules. If you attempt to manage these rules in a single book and map them each explicitly to the process or decision-making task then you will be overwhelmed with complexity.

Faced with a "big bucket of rules," teams try to lessen the rule management problem by either "rolling-up" rules into larger, less-granular rules or by only mapping some of the rules to the decision-making. Granularity of rules is important for clarity and precision while traceability and impact analysis matter for ongoing management so neither of these approaches works well.

A decision model allows for a structured decomposition of decision-making and the mapping of rules not just to the top-level decision but to more fine-grained decisions. Rules can remain granular, and all the rules can be mapped precisely.

Benefit #3: Agile Business Rules Automation Projects

Focusing on business rules worked well when companies did waterfall projects. Identifying, understanding, and writing all the business rules for a business area in a single analysis phase is a classic step in a waterfall project. In a world where projects are increasingly using Agile approaches, however, this kind of details-first approach is no longer acceptable and organizations need a new approach.

A decision model can be developed incrementally, focusing on the detail in one area in each phase or sprint. An initial high-level model scopes the whole project. One part of the model can be expanded on and developed independently. The rules needed for just the identified decisions can be identified, described, and implemented. Value is added even though the whole model is not implemented. This approach can be repeated for each phase or sprint, and the overall model provides a structure, showing how they fit together while supporting a more iterative, agile approach.

Benefit #4: Effective integration of Big Data Analytics

Decisions involve more than business rules — analytics play a critical role in many decisions. Beginning with business rules tends to obscure this fact, focusing teams only on business rules when data-driven analytic approaches would be more effective. In fact, decisions are more often made by a combination of business rules and predictive analytics than by one or the other alone. While a fraud decision may be driven mostly by an analytic prediction of the likelihood of fraud, the specific action to take may well be driven also by business rules about the customer, the size of the transaction, and other considerations. For instance, we might not reject a high-risk transaction if it is for a small amount for a good customer who is traveling overseas because we don't want to risk irritating them.

Similarly, decisions that have historically been considered completely deterministic, such as pricing, increasingly use analytics and business rules in combination, dynamically adjusting prices to reflect customer churn risk.

Organizations need to be open to this and need therefore to ensure that teams don't become fixated on using only business rules or only analytics in their solutions. Because decision modeling supports both business rules and analytics, it allows for this flexibility in a way that business rules-centric approaches do not.

Do all business rules lead to decisions? No, they don't. But when they do, when the business rules you want to capture and execute are related to decision-making, then it's critical you put decisions first and business rules second. Decision Modeling works as an approach; there's an emerging standard, and Decision Modeling is under consideration for the next release of the IIBA® BABOK®.[5]

As someone else said recently, "Decision Modeling is going to be a thing, people."

References

[1] Ronald G. Ross, "Three Major Myths of the Business Decision Space — And Why They Matter to Business Analysts," Business Rules Journal, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Jan. 2014), URL: http://www.BRCommunity.com/a2014/b737.html. ![]()

[2] The differentiation of decisions into Strategic, Tactical, and Operational decisions was, I think, introduced by Neil Raden and me in our book Smart (Enough) Systems: How to Deliver Competitive Advantage by Automating Hidden Decisions, Prentice Hall, (2007). ![]()

[3] Including a white paper "Decision Modeling with DMN" from Decision Management Solutions (http://decisionmanagementsolutions.com/decision-modeling-with-dmn) and active discussions with many external links on the LinkedIn DMN group (http://www.linkedin.com/groups/Decision-Model-Notation-DMN-4225568). ![]()

[4] The Decision Model and Notation (DMN) Specification 1.0 Submission is available from the Object Management Group at http://www.omg.org/spec/DMN/Current ![]()

[5] The International Institute of Business Analysts® Business Analyst Body of Knowledge® 2.0 is available at http://www.iiba.org/babok-guide.aspx, and Version 3 is expected to enter community review in Q1 2014. ![]()

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.