Business Architecture Essentials: Synthesizing your Architecture's Strategic Guidance

Introduction

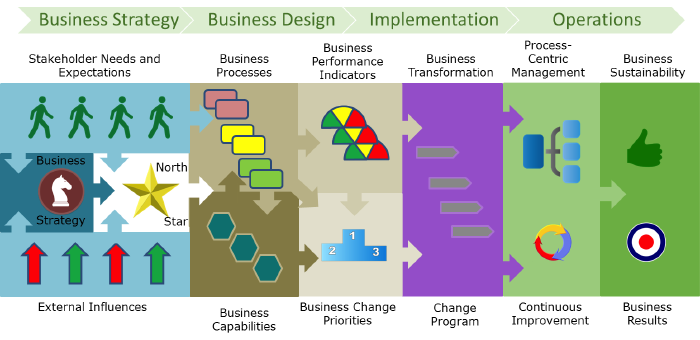

In the first article of this series, I discussed the current interest in Business Architecture that has been brewing in the last little while and also discussed some of the frameworks that professionals have been looking at for inspiration. The first article was intended to provide an overview of the field and it introduced an overarching set of concepts that we in Process Renewal Group have been successfully using to classify and categorize issues of concern. In the second article, I tackled the challenge of scoping your architecture and the usefulness of selecting what's in and out, based on value chains rather than organization charts. The third tackled the challenge of defining the expectations of the external stakeholders in terms of their core service needs and experiences. All of these play an important role in determining the decision criteria for everything that is to follow, especially the determination of a consolidated set of strategic statements needed to guide many architectural decisions.

I will continue to view the organization or value chain as a black box for now to ensure we know what the overall drivers, goals, and objectives are and that they are used explicitly to make decisions among competing choices for change prioritization and capability investment. I will continue to take an external stakeholder perspective and consider any external pressures, as well as leveraging pre-existing strategic statements. All must be balanced to arrive at an unequivocal guiding North Star that is commonly shared, rather than arguing from the perspective of internally conflicting personal interests.

I will continue to view the organization or value chain as a black box for now to ensure we know what the overall drivers, goals, and objectives are and that they are used explicitly to make decisions among competing choices for change prioritization and capability investment. I will continue to take an external stakeholder perspective and consider any external pressures, as well as leveraging pre-existing strategic statements. All must be balanced to arrive at an unequivocal guiding North Star that is commonly shared, rather than arguing from the perspective of internally conflicting personal interests.

What makes up the Strategic Guidance?

The knowledge we should have now documented regarding stakeholders expectations of value and experience, described in the third article, provides a critical set of considerations to the context of the processes we conduct. It defines the ultimate capabilities we need to have to be able to attain results and helps us formulate the right balance in our strategic intent, reconciling a number of perspectives that may otherwise be in competition with one another. Sound strategic guidance also requires a broad analysis of the business environment within which the organization or value chain exists. This includes all of the favorable factors and unfavorable ones that will affect strategic and architectural choices. Once we understand these issues we can craft a thoughtful strategy.

External Pressures

Along with understanding our external stakeholders we must also have a discussion to gain a common view of the current and anticipated external realities of the business or the chosen value chain. Many, if not most, of these contextual factors are beyond our control and possibly our influence. They are often not considered thoughtfully or are optimistically willed away. Some will have an impact on us for a short or a long time and cannot be ignored. They must be accommodated for in our planning.

There are several categories of pressures to consider and several schemes to do so. One that I like a lot is the STEEPL structure: Social, Technological, Economic, Environmental, Political, and Legal. Some are more relevant than others, depending on the industry and the time. Some will grow worse over time, and some will get better or even go away. Hazarding a guess to the severity and vector of each can be a hazardous proposition. The joint consideration of what each means to us is essential.

I will look at each of these in order.

Social

Social pressures happening in the world at large or even in a defined market are hard to change and, once underway, hard to resist. Examples include:

- The age distribution of the North American and European populations versus new world countries

- The unacceptability of smoking in buildings

- The demand for privacy versus transparency of personal data

- The rise of the millennials' expectations of work / life balance

- The expectations of environmental sustainability

Technological

There can be no denying the impact of technology on markets, stakeholders, and companies. The fundamental expectation of experience from customers is one of digitization and sharing. Examples include:

- The universal adoption of smart mobile devices

- Cybercrime, electronic spying, and cyber-attacks

- Information sharing across multiple channels and devices enabled by cloud-based infrastructures

- The ubiquitous accessibility of wireless services

- The continuing predominance of ERP software in businesses

Economic

- Extreme swings in currency valuations

- The price of commodities

- Hangover from the financial crisis

- Interest rates

- Distribution of income by social class

Environmental

- Weather events / climate change

- Food safety

- Worker safety

- Carbon footprint / pricing

- Water / air quality

Political

- Government changes

- Government gridlock

- Global political pressures

- Refugee crises

- Terrorism

Legal

- Tax changes

- Trade barriers / agreements

- Regulatory reporting

- (De)regulation

- Worker rights

These are but a few of the potentially relevant factors that may affect your organization or value chain. Depending on your situation each of these may provide an opportunity or a threat or be irrelevant. It all depends on your strengths and weaknesses with regard to each, relative to those you are competing with. Selecting the ones to be ready for and how to do so along with your earlier stakeholder analysis (Article 3 in the series) will be a foundation for your strategic response and your business design.

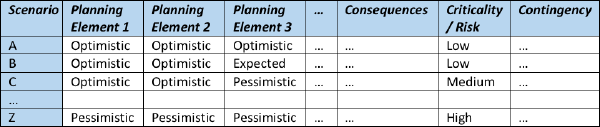

Business Context Scenario Analysis

In a world of VUCA (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity) the potential variations in those STEEPL factors of greatest relevance to your circumstances must be assessed to determine the ones that bring the most potential variation and therefore risk to the business if we presume incorrectly. Any business design must work for a range of possible future business scenarios, not just for one set that is assumed based on today's situation. The relative certainty / uncertainty may be a major consideration in defining requirements for processes and capability adaptability. Your business design must account for key driver variables affecting the future for which our solutions must be agile and resilient enough to reduce or mitigate operational and business risks.

The subset of the planning elements from the STEEPL assessment (for example products, regulation, price, competitors, etc.) that have the highest impacts and greatest uncertainty should be examined for a range of possibilities. Each factor will be looked at to determine if the direction each is taking is inevitable, strongly possible, or simply possible. You will have to sort out, for each of these, whether or not for you the answer is optimistic, as expected, or pessimistic. The combinations of these can then be synthesized into a small set of alternative scenarios and validated as low to high risk. Some of these may be positive for the organization if it is ready to change quickly or if the designs chosen are inherently versatile. Some of these will be negative and represent real threats if the value chain is brittle and cannot bring sufficient strengths to weather the storm. From this assessment we will pick a small set to become our evaluation criteria to test any business models and architectures for robustness and flexibility. The table illustrates the range of possibilities from which we would derive no more than five to seven combinations for business architecture and business design testing.

Defining Strategy

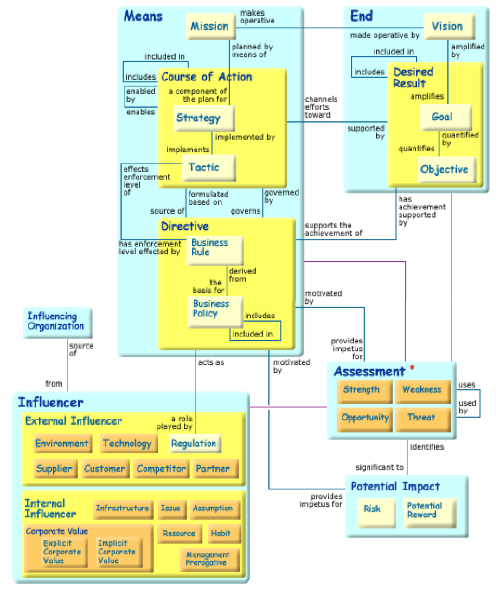

There are a myriad of ways of defining a strategy for an organization or value chain. The one that we tend to follow is the Business Motivation Model (BMM), originally conceived by the Business Rules Group and formally adopted by the Object Management Group. We will also consider the benefits of questioning the Customer Value Proposition.

The Business Motivation Model

The main message to be taken from this standard is that there needs to be a clear distinction between the ends we strive for and the means by which we attain them. 'Ends' are results of the end-to-end process work performed to benefit the recipient stakeholders as we discussed in article 3. 'Means' are the actions we take and the mechanisms we employ to take them. Ends are what we aim to achieve. Means are what we need in order to achieve the ends. The misunderstanding of the difference is frequently a key source of confusion for those defining strategic intent and the strategy itself (these are different). In this regard it is not unusual to see organizations mix up Mission and Vision.

A 'Mission' is what the organization or value chain is mandated or chooses to do for those it serves. Unless the business changes, the Mission statement does not substantially vary over time.

On the other hand, the 'Vision' is what we are trying to achieve by some defined point in time (a planning horizon). It should be measurable with clear comparable units of measure. The Vision may change from planning period to planning period. It should reflect the result or outcome of what we will do if we do the right things right.

A 'Mission' is what the organization or value chain is mandated or chooses to do for those it serves. Unless the business changes, the Mission statement does not substantially vary over time.

On the other hand, the 'Vision' is what we are trying to achieve by some defined point in time (a planning horizon). It should be measurable with clear comparable units of measure. The Vision may change from planning period to planning period. It should reflect the result or outcome of what we will do if we do the right things right.

Being strong at actioning great Means (methods and tools) is in and of itself no guarantee of achieving the Ends if they are not aligned. Delivering outputs according to quality standards does not assure that your business outcomes are going to be achieved. Being efficient with resources does not mean you have satisfied the recipients' needs or that you have been effective. We always start with the Ends and then determine the courses of action required to achieve them. Otherwise we easily get caught up in building great processes and capability that do not match a purpose and do not enable business results. We figure out what the right things are (the role of executives) and then determine what is the right way to accomplish them (the role of managers). To support the Mission we will have to define the right courses of action. To support the Vision we will have to establish a number of strategic goals (general statements of intention) and also a set of strategic objectives (target measures of goals with crisp performance indicators). Goals are not Objectives. BMM makes that clear. All of the key Ends and Means choices are influenced by the outside stakeholder goals and objectives as well as the outside pressures as documented in our STEEPL analysis and Business Scenarios. Clearly there is a tricky balancing act to conduct to gain agreement among executive teams.

Value Proposition

Another useful discussion to delve into is that of the Customer Value Proposition. A Customer Value Proposition is a business or marketing statement that describes the reasons a customer would buy a product or use a service from the supplying company. It reflects a philosophy, real or aspirational, that should persist in everyone in an organization in terms of the focus of the company and all of its staff. It is operational and cultural. It is specifically targeted towards customers more than other external stakeholders such as employees, owners, or regulatory bodies. Made popular in their book, The Discipline of Market Leaders, Treacy and Wiersema advocated that organizations should excel in one discipline and retain a base level of sufficiency in the others and not try to be leaders in all three at the same time. They argue that this will lead to a lack of focus and alignment and will miss the opportunity for marketplace differentiation. The typical three propositions or styles are: Product Leadership, Customer Intimacy, and Operational Excellence.

Product leadership

In Product Leadership there is a focus on innovation and turning insights into breakthrough technologies, products, and services, not just once but on a continuing basis. World-class processes and capabilities will be found in the product and service lifecycle area. Time-to-market is a major performance driver. Examples of this proposition would be Apple that is innovating with new products continuously. Another is Dyson, with its creative vacuums and air movement product lines. Often prices are higher but a large proportion of the market will pay the uplift happily.

Customer Intimacy

In Customer Intimacy the focus is on specialized and personalized customer service and a unique relationship with each customer. In this proposition the customer relationship is more valued than any particular product. It has a strong service orientation. An incredibly strong sense of trust is established in more of a partnership style. World-class processes and capabilities are found in and around customer relationship management and the creation and sustainment of loyalty. Share-of-spend in the relevant market categories is a major performance driver. Perhaps the most renowned example of this proposition is Nordstrom, the high-end retailer of fashion and lifestyle products in the US and Canada that has a very strong following of customers who buy a lot of their clothing through a personal shopper relationship when in the store and also when not. The Nordstrom personal shopper will always have her or his eye open for suitable items that may be held for the customer to come in and try. Another, surprisingly, is online retailer Amazon who is always striving to offer the most appropriate products but doing so by using its incredibly strong data analytics capability. Amazon is always experimenting and putting together proposals that are not mass offers but individually tailored ones. It knows a lot about its customers' buying habits.

Operational Excellence

In Operational Excellence the focus is on the efficiency of day-to-day operations and the price and simplicity of delivering and buying products and services. This is the domain of traditional Lean and Six Sigma programs whereby reliability, reduction of waste, and consistency are a prime focus. Unit costs and price competitiveness are major performance drivers. An example of Operational Excellence is Walmart or Costco. Both of these organizations feature price as a differentiator and extremely efficient supply chain management and overall operations to the point that when a supplier finds an efficiency in its own operations the distributor (Walmart or Costco) to the consumer market will demand a share of their suppliers' saving in the price to them.

Value Propositions and Markets

Although there may be a predominant proposition particularly prevalent in a particular market, there is often room in many markets for different companies with different value propositions. It may not be tied to a particular income segment. There is typically not one for an industry that all players have to adopt. It is a matter of strategic choice. It is not unusual to find a scenario whereby a consumer will drive to Nordstrom in her Tesla to buy a fashionable coat but drop into Costco to buy lower priced food items and on the way home get a five dollar coffee at Starbucks. Whatever your choice may be, once made the proposition must be embedded in the design of your processes and capabilities and in the culture of the organization, as witnessed by consistently-aligned behaviors in all staff and reflected in management decisions that support the proposition intent.

The North Star

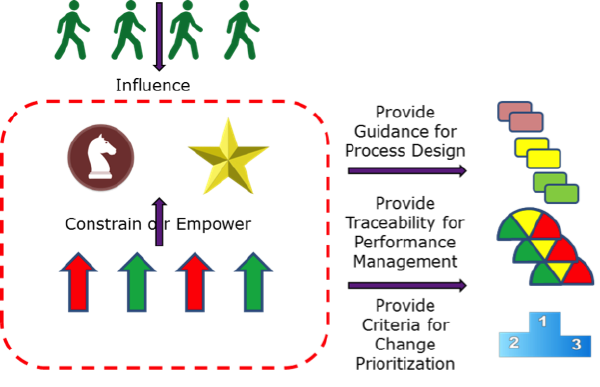

At Process Renewal Group we synthesized the factors mentioned so far into a simplified set of statements that make it easier to communicate direction and to align the business aspects of architecture. By melding the conclusions from the External Pressures and Business Scenarios, the strategic discussion of Ends and Means, the Stakeholder Expectations of value and experience, and the Value Proposition we can arrive at a set of unequivocal decision criteria that balances interests that may otherwise compete and pull us in different directions.

Especially useful in this synthesis are the stakeholder expectations. This is the set of results that we must ideally deliver to satisfy the needs and experiences of our stakeholders to sustain healthy relationships and deliver on the value proposition. If we did the expectations work described in the third article of this series and have the needs, experiences, and measures of value, we can inform process improvement as well as architecture guidance. From this we will later be able to derive the specific outcomes for particular processes and projects should we decide to work on improving them.

From an architectural point of view we can now synthesize a set of four to seven directional guiding statements. We call this the North Star. (You may name it the Southern Cross if you are south of the equator.) The implication is to establish a fixed point for all to use in the remaining architecture work, regardless of background or perspective. It is our experience that it is better to surface any differences of opinion or strategic misunderstanding at this early point rather than later, where it will surely come up and in much more challenging circumstances.

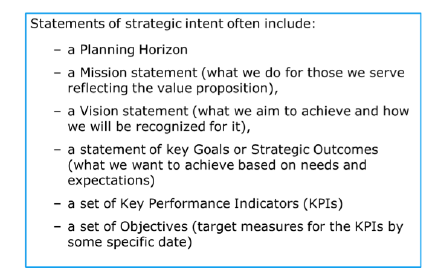

The establishment of the set of statements is not an exact science, even with the work we will have done and insights gained so far. The discussion to arrive at the list is perhaps as valuable as the list itself. The statements should try to be consistent with several proven characteristics:

- Ideally have 4 – 7 statements

- Each should have a vector (increase, decrease, sustain, or equivalent words)

- Amplify shared expectations among stakeholders

- Balance inherent conflicts among stakeholder outcomes (more than one perspective)

- Weight the value of each out of 100% for later consideration

- Ensure all statements are measurable with clear KPIs and performance targets

The diagram illustrates a North Star for ourselves: Process Renewal Group. Remember, the percentages are how important each outcome statement is, relative to one another. When we look at prioritization later this will become invaluable.

I recommend that in looking at all the prior knowledge gained so far, first of all look for desired outcomes that are of value to multiple stakeholders, such as customers, suppliers, and staff, and identify those first, rewording in the process to work overall. These will likely be the highest rated. Determine ones that are uniquely critical to the customers and other downstream stakeholders. Next, find statements that provide results for owners/shareholders/governing boards. Subsequently, find ones that are essential for suppliers, compliance bodies, and employees if not already covered by the prior ones. Examine these to ensure that any other factors are considered and the choices reflect the essence of where you want the organization to end up. Add the vector. Determine the KPI. Gain agreement from the executives. Now you can negotiate the weightings, which is often a difficult exercise to get done because it is a prioritization exercise that no one willingly wants to do. Do not do it solely from the executives' personal motivations but from the stakeholders and overall business. However, make sure you have executive acceptance. They have to own it and use it later. Also, do not allow them choice of not choosing a weighting factor. When they decide not to differentiate they are saying they are all equal. Ask "Is everything truly of the same importance to the organization?"

Having this discussion and making the choice are essential to business architecture since this allows us to rationally recommend what to do with the design of models and where change should occur.

Future Articles

The knowledge gained here is more than an artifact to be stored. The insight gained by the participants and the agreement by management will pay off throughout. If you do not do this I guarantee that later you will wish you had. The architecture team will be able to relate to the business and talk their language. The process architecture models coming in the next article and the capability definitions subsequently will have a reason for being, and everything will connect to value creation. The performance management system will connect to the top of the scorecard. The decisions and rules will have a reference point. The roadmaps will deliver the most value first.

That's the way I see it.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules