Developing your Capability Architecture: It's All about Being Able to Get Things Done

Introduction

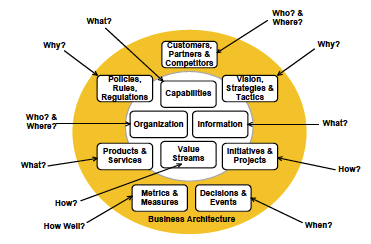

In the first column of this series, I discussed the current interest in Business Architecture that has been brewing recently and also discussed some of the frameworks that professionals have been looking at for inspiration. The first column was intended to provide an overview of the field, and it introduced an overarching set of concepts that we in Process Renewal Group have been successfully using to classify and categorize issues of concern.

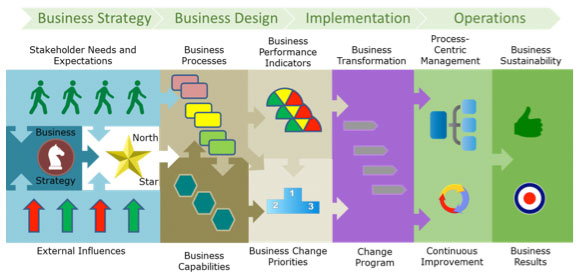

Figure 1.

In the second column, I took on the challenge of scoping your architecture and the usefulness of selecting what's in and out based on Value Chains rather than organization charts. The third dealt with the challenge of defining the expectations of the external stakeholders in terms of their core service needs and experiences. The fourth looked at the strategy of the organization from understanding external pressures and threats, looked at various possible futures, and looked at the strategic intent (ends) and strategies and tactics (means) along with the derivation of a 'North Star' for architectural guidance and decision making. The fifth delved into the development of the Business Process Architecture, which I believe is a domain of the first order, describing what work gets done operationally and is not a derivative of anything else. All of these models are absolutely essential to establishing a relevant architecture that makes business sense.

In this column, I will tackle a topic that has both intrigued me and driven me crazy at various times. There is a well-established Enterprise Architecture camp, often found within IT groups, which seeks to understand the business requirements for technology planning, prioritization, and implementation, that sees 'capability' as the central concept of Business Architecture. There are other points of view, especially from process advocates, that see it a little differently. I will delve into some of these perspectives and try to make sense of some of the thinking to ensure that no matter your point of view we keep our approach business oriented and not just about IT.

The capabilty aspect of business architecture is still emerging and at this point there are no indisputable standards in place, although several groups maintain strong points of view and are working on proposals for standardization. Several large consulting and technology firms are also pushing their own views with the apparent goal to differentiate themselves and land large implementation projects down the line.

The capabilty aspect of business architecture is still emerging and at this point there are no indisputable standards in place, although several groups maintain strong points of view and are working on proposals for standardization. Several large consulting and technology firms are also pushing their own views with the apparent goal to differentiate themselves and land large implementation projects down the line.

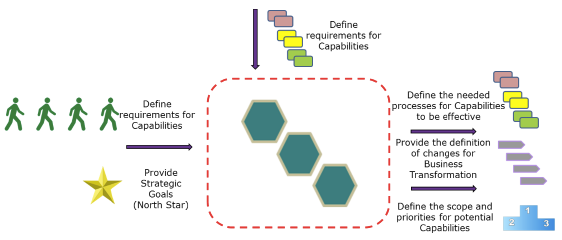

Within the methodology discussed in this series, the exchange of knowledge looks like the following:

Figure 2.

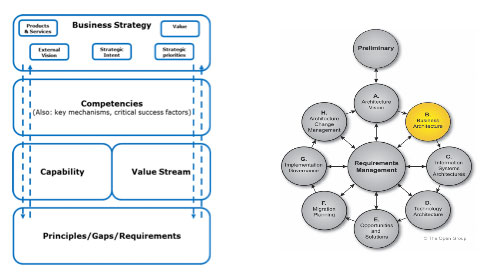

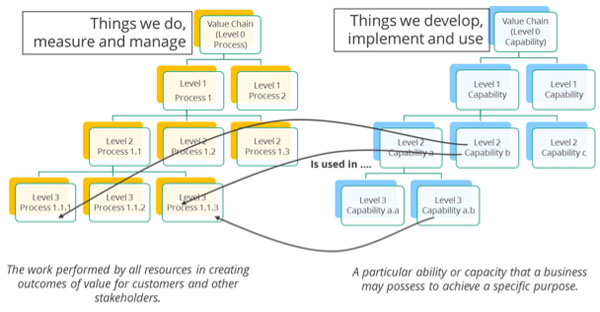

The Open Group has postulated that capabilities are essential to both business architecture and to IT solutions. They are currently working on a new view, not yet public, that places business architecture outside their classic models (Figure 3) as a precursor or umbrella to all other aspects of IT architecture. In the TOGAF perspective, capability is a key concept along with the value stream models.

Figure 3.

The most comprehensive work available to define a number of business architecture views and a main promoter of capabilities is The Business Architecture Guild in its Business Architecture Body of Knowledge (BIZBOK). Although I do not agree with every perspective and classification taken in it, on the whole I find it a very useful guide that is updated regularly as experiences evolve. This is a good reference since it has a strong value-delivery orientation, consistent with our approach at Process Renewal Group. It includes a large section on capabilities and the value streams required to apply them.

What Is a Business Capability?

In the common vernacular, the term capability is typically associated with the level of ability of something or someone to achieve some purpose. It is typically applied to some thing: some physical object such as a car or a toaster, some human resource such as the CEO or the call center agent, some piece of information technology. The list goes on. It can also be associated with something more abstract such as a company or group. The nature of the term in the English language is that it is structured as needing a context. Is it the capability of a person, an organization, a value chain, value stream, a process, a piece of software, a facility or piece of equipment that we are talking about? The term 'capable' as defined by Merriam-Webster's dictionary means 'having attributes (as physical or mental power) required for performance or accomplishment'. Therefore, for layman usage it is essential to know the purpose of your organization, your business processes, or your assets in order to know whether to assess it as being a suitable capability versus one that is lacking, relative to what's needed. A hammer in the right hands is very capable of enabling you to put a nail into a piece of wood if that is your purpose but not so capable in any hands if sawing that piece of wood in half is what's needed. 'Capability' then needs both a business context as well as a set of criteria (purpose) for an assessment.

In many business architecture circles the term has evolved to become an architectural concept in its own right without regard to the actual level of its ability to perform. This is quite different than what many people are used to. It is simply used as a name for a concept without regard for its needed level of ability. As an example, in a capability map 'Credit worthiness assessment' does not imply how good you are at it or how good you have to be at it, only that you need that capability in your business at some level of ability to perform. The level will depend on your business and your strategy. In a similar sense, process names are treated similarly in the process architecture. The process 'Resolve complaint' does not tell you how well it works or if it needs to be much better. It just says that conceptually there is a process for that which should be in the architecture somewhere so we can determine if there is a performance gap and if we should close it.

The Business Context

Capability in a business architecture sense has come to mean what is required to enable or contribute to the creation of value towards the intent of the organization or the value chain stakeholders who receive our goods and services. As such, there is a strong alignment of 'capabilities' with value-creating 'business processes' although many business architects and industry models have lost sight of that critical value connection and focus almost exclusively on functional capability maps, to the exclusion of alignment to process architecture maps.

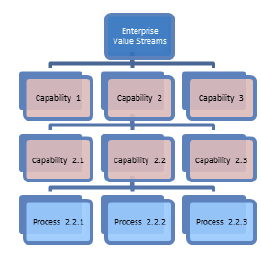

It is important, however, not to build these maps into one another. The figure on the right shows a common misconception often heard in architecture groups as to how the two are interrelated. In my experience, it is simply not correct since good architectural principles, as reiterated by John Zachman, simply state that you cannot decompose one concept (architectural domain — aka Zachman column) into another type. If you are going to have capabilities and processes, you have to maintain the integrity of each domain individually and associate them with one another through a meaningful set of relationship meanings. In architecture we should be representing processes and capabilities in a many-to-many relationship as shown below in Figure 4. Both are needed.

Figure 4.

In a recent personal experience of renewing a passport from another country (I am Canadian), I experienced the difference. The passport office processed the application and handed it off to a courier to ship internationally back to me. The courier company had told me earlier that international shipping was a key capability of the company, but they did not view it as a process. When the envelope did not arrive as promised for several days I concluded that there may have been capabilities on the capability map but the process that used those capabilities failed me when I needed it, for whatever underlying reason. We need to be capable, but we also have to get the work done!

Some Principles

Key Traits of Robust Business Capabilities

A sound enterprise-level view of all capabilities will exhibit some key traits as listed in the Business Architecture Guild's BIZBOK.

- Characteristics:

- Provide business centric views of an organization

- Are defined in business terms

- Define what a business does

- Are stable

- Are defined once for an enterprise (or component thereof)

- Decompose into more capabilities

- There is one capability map for a business (a business may have more than one enterprise or be a part of one)

- Map to other views of the business

- An automated capability is still a business capability not an IT one

- If the mapping team cannot define a capability it probably is not one

Key Principles of Robust Business Capabilities

All of the above principles are true for business processes as I outlined in an earlier column for a value-creating process architecture and process definition. The main difference is that capabilities are expressed using nouns or gerunds, not verbs, and business processes (or value streams) are expressed as verb-noun constructs.

- Just like processes, the capability map should:

- be organizationally agnostic

- be technologically agnostic

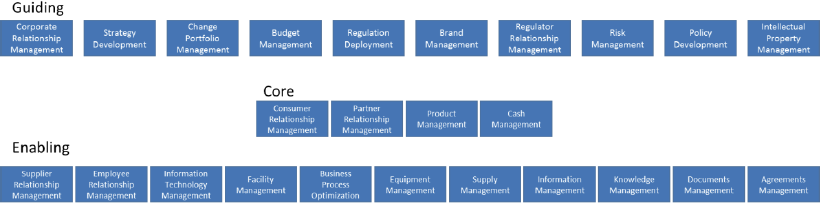

- share a consistent classification structure of Core, Guiding, and Enabling

- initially keep to a limited depth of structure (typically, 3- to 4-levels deep)

- describe 'what we do' and not so much the variations in 'how we do it'

- be stable over time (unless the business model itself is changed)

- A capability's impact should:

- be measurable

- be traceable to higher-level capabilities

- be aligned with other capabilities at the same level

Stable Capabilities Start from Business Objects

The BIZBOK defines a capability as "a particular ability or capacity that a business may possess or exchange to achieve a specific purpose or outcome." A capability map should contain "a concise, non-redundant, complete, business-centric view of the business." The starting point for identifying capabilities is most simply served by taking a unique business object orientation. Business objects (or business concepts) provide a foundation. They are not capabilities themselves but allow us to ask what capabilities we need to make each one effective. These concepts can be discovered by identifying specific types of relationships with external stakeholders and also with other particular objects of interest (assets and other softer business concepts). The key question is what things have to be managed by the business. To find a comprehensive list of possible relevant business objects, we can identify all relationships and all items that must be managed. In effect, we are striving to 'normalize' them. That means having one place for everything and no redundancies. For our consumer bank example we could find a number of relationships to be managed and place them into our three categories as we did for business processes in a prior column. Some of these could be:

- Guiding

- Bank Board

- Bank Regulators

- Core

- Consumers

- Bank Partners

- Enabling

- Suppliers

- Technology Partners

- Employees

- Facility Service Providers

Each of these can have several sub-types which can be shown as a decomposition. For example, a consumer may be subdivided into high wealth consumer versus transactional consumer types. Each may have unique needs and value requirements, but some needs will be shared. The commonality could even spread to other relationships. Are there attributes of a customer relationship that are similar to a partner relationship, such as the signing of a contract? You will have to determine if they can be satisfied by a common set of capabilities or if each is truly unique. How much of the customer cycle is similar to the partner cycle, and where are the differences, if any?

Other business objects can be discovered by looking at the concept or information model of all information items that have to be managed by the business (if you have one). For each object to be managed, different capabilities will be needed at different times.

For the consumer bank, some potential high-level business objects, in addition to relationships, may be:

- Guiding

- Business Strategy

- Budgets

- Policies

- Business Rules

- Regulations

- Risk

- Brand

- Intellectual Property

- Core

- Financial Products and Services

- Financial Resources

- Enabling

- Technology

- Facilities

- Business Processes

- Equipment

- Supplies

- Information

- Knowledge

- Agreements

Again, some of these may have distinctions with sub-types. You will have to determine how deep to go.

Let's look at some capabilities for our consumer banking example. The consumer set will be relevant to the management of the relationship with the consumer but will not include the capabilities of managing the financial products and services that they are sold to them and that they use. Those will have their own capabilities. The regulator set will deal with the management of the regulator relationship but will not deal with a regulation or the policy needed to mitigate it per se. The facility provider (supplier sub-type) relationship will be the subject of a set of capabilities, but the facility itself will be a different set. It is important not to mix these as capabilities; otherwise, the goal of capability normalization will be lost, and change will be more complex than necessary. They will be connected through the vehicle of the value-creating business processes that use them.

In Figure 5 at the top level of the capability for our consumer banking example expect to see something like:

Figure 5.

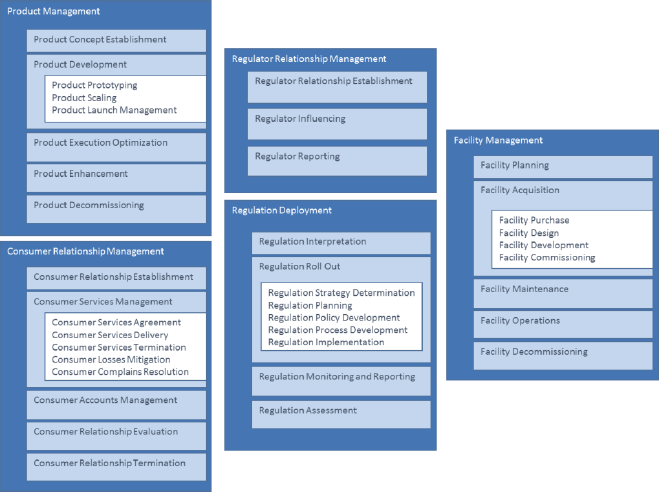

By looking at this map it is easy to see why, at a high level, capability advocates and process advocates may not see the need for one another's perspective, since both approaches are based on making relationships work well for end-to-end value delivery and on ensuring that all the business objects are working as needed. Diving deeper, however, lets us see how there can be higher-level capabilities and component levels. Let's look at some decompositions of a few high level capabilities from the overall map by asking, "What are the things that have to be managed at a more-detailed level?" I have picked several illustrations of capabilities to the second and third levels in Figure 6. These are not exhaustive, and possibly wrong, but the pattern can be seen.

Figure 6.

From this illustration it is obvious that there can easily be hundreds of level-3 and thousands of level-4 capabilities. Rather than going deeper it may be more appropriate to do a top-level skeleton (capability map as shown in Figure 5), covering all the macro objects (as we did with the process architecture) and only drill down into the ones that we deem priorities. I will deal with this prioritization of processes and capabilities in a future column.

Future Columns

The business capability perspective discussed here is in its early days, and there is still a good deal of controversy between business process and capability camps. There are many ways to do business architecture, and you will have to make your own choice, of course. Many organizations are still struggling to determine what to do. There is a lot of angst between business architects, enterprise architects, technology architects, business process professionals and, of course, operational managers regarding what is needed and how to tackle the capability and process perspectives. I will deal with how processes and capabilities interact in a future column.

That's the way I see it.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules