Developing Your Process Architecture: It's All About Your Work

Introduction

In the first article of this series, I discussed the current interest in Business Architecture that has been brewing in the last little while and also discussed some of the frameworks that professionals have been looking at for inspiration. The first article was intended to provide an overview of the field, and it introduced an overarching set of concepts that we in Process Renewal Group have been successfully using to classify and categorize issues of concern. In the second article, I tackled the challenge of scoping your architecture and the usefulness of selecting what's in and out based on Value Chains rather than organization charts. The third dealt with the challenge of defining the expectations of the external stakeholders in terms of their core service needs and experiences. The fourth looked at the strategy of the organization from understanding external pressures and threats, looking at various possible futures, looking at the strategic intent (ends) and strategies and tactics (means), and the derivation of a 'North Star' for architectural guidance and decision making. All of these are absolutely essential to establish a relevant architecture that makes business sense.

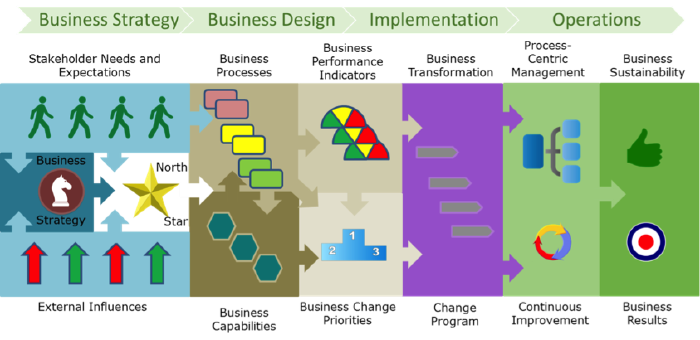

Figure 1.

At this point in the series of articles, I will stop viewing the organization or value chain as a black box and will delve inside. I must apologise for writing such a long article. This is an essential part of business architecture and deserves attention.

I will continue to take an external stakeholder perspective using our knowledge of the drivers, goals, and objectives of the North Star and especially the nature of the products, services, and information exchanged. This will give us the start and end of all comprehensive processes that create mutual value regardless of organizational structure.

I will continue to take an external stakeholder perspective using our knowledge of the drivers, goals, and objectives of the North Star and especially the nature of the products, services, and information exchanged. This will give us the start and end of all comprehensive processes that create mutual value regardless of organizational structure.

What Is a Business Process?

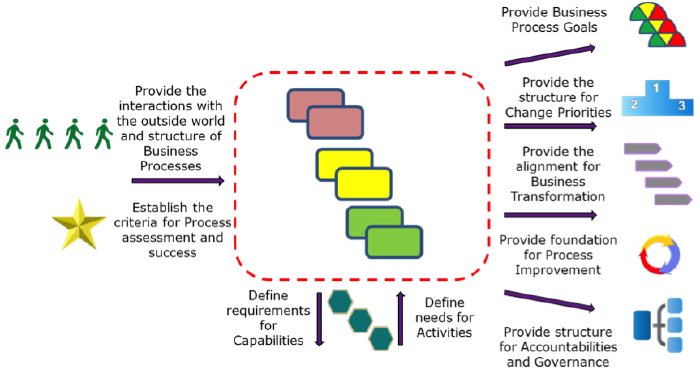

The knowledge we should have now documented regarding stakeholders' expectations of value and experience (described in article 3) provides a context for our processes that does more to directly connect the other architectural domains than any other. Figure 2 shows the criticality of the Business Process perspective in synchronizing many other aspects of the architecture.

Figure 2. The criticality of the Business Process perspective in synchronizing other aspects of the architecture.

Let's start out by being clear what we mean by the term 'Business Process'. A process perspective provides a critical foundation for effective business operations and change. Simply put, business operations are simply the execution of your business processes. Your processes are your work, done by people or technology. The process architecture organizes the work required to deliver the business strategy. End-to-end processes assure a business perspective in business architecture because they deliver the day-to-day business results to outside stakeholders and provide the measurement structure needed to monitor and manage those results. To be relevant, organizations must start with a robust set of business processes that everyone understands and figure out what it needs to have in place so it can deliver operational business results. It has to start with a clear focus on running the business.

A focus on processes comes from a deep-seated passion for making the business run better, not just building systems — that is, improving how processes execute operationally every day in order to continue to deliver value and optimal outcomes. This is job one. It's what organizations do. It's how they survive, thrive, and grow. This understanding must come before consideration of technologies or organization charts, no matter what is the latest technological fad. A business must start by striving to enhance the performance of business operations end-to-end for customers and other stakeholders. Doing the right work and making the right operational decisions is what processes and business operations are all about. It's why we get rewarded or punished in the marketplace.

A focus on processes comes from a deep-seated passion for making the business run better, not just building systems — that is, improving how processes execute operationally every day in order to continue to deliver value and optimal outcomes. This is job one. It's what organizations do. It's how they survive, thrive, and grow. This understanding must come before consideration of technologies or organization charts, no matter what is the latest technological fad. A business must start by striving to enhance the performance of business operations end-to-end for customers and other stakeholders. Doing the right work and making the right operational decisions is what processes and business operations are all about. It's why we get rewarded or punished in the marketplace.

A solid process foundation is needed to connect the dots among strategic intent, business relationships, business capabilities, enabling technology, and human resources (to name a few). This end-to-end process structure is essential to achieve digitization or customer centricity goals and ensure that all business resources are optimally aligned towards a common objective and not working at cross purposes. To do this, organizations need to architect their intellectual and physical assets and shared capabilities using business processes as the glue, tracing all work to enterprise intent and stakeholder outcomes. A practical, shareable, and implementable business-process-driven change portfolio will ensure organizations choose the right transformation initiatives and optimize operational business outcomes. From this, organizations can scope, analyze, and design new ways of working using process innovation and improvement practices and models. These will help organizations realize any new business model intent and prescribe what's required technically, as well as organizationally and culturally.

Some Principles

The Business Process Manifesto

The Business Process (BP) Manifesto states that "an organization's business processes clearly describe the work performed by all resources involved in creating outcomes of value for customers and other stakeholders." In other words, a business process is not just a list of connected activities but a value-creating proposition for external service recipients.

It emphasizes an end-to-end perspective, starting with those in our external world as defined in Articles 3 and 4 of this series and working back to our internal operations. These manifesto guidelines emphasize this strategic point of view.

- A business process should create measurable value for customers and other stakeholders by delivering outcomes that satisfy their particular needs and expectations.

- A business process delivers outputs to and receives inputs from external customers and stakeholders as well as other Business Processes within the organization.

- A business process should be guided, formally or informally, by the organization's business mission, vision, goals, and performance objectives.

The Manifesto goes on to say that "a business process model represents the fundamental abstract structure and organization of a Business Process or set of Business Processes as described by their activities, their relationships to one another and to the environment in which they operate." This structural perspective emphasizes integrity, completeness, and decomposition of critical knowledge. This view is well supported by comprehensive process frameworks such as the Process Classification Framework® (PCF) from APQC. The Manifesto also states:

- The complete set of business processes of an organization describes all the work undertaken by that organization.

- A business process model contains all the information required to describe the business process and its environment.

Key Traits of Robust Process Architecture

In order to manage business processes as reusable assets, organizations need to establish a robust process architecture (enterprise process map) that leverages end-to-end thinking. A sound enterprise-level view of all processes will exhibit some key traits.

Organizationally Agnostic

Business processes do not directly correlate to an organization's formal reporting structure. Certainly the work described by the processes in the architecture, at some level of detail, will be performed by people or technologies conducting roles within an organization, but end-to-end value creation is a factor of the stakeholder relationships with external parties, not the internal hierarchy. A good test of the quality of an organization's process architecture is to ask if the process structure could survive a drastic reorganization. If the answer is 'no' then it is a poor process architecture and will have to be changed often. The architecture can be changed, but keep in mind that customers will judge your business by how well you meet their expectations of process delivery, nothing more or less.

Technologically Agnostic

The processes of the organization are typically enabled by technological services or capabilities. It is especially tempting, given the availability of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) suites and other off-the-shelf software, to follow the vendor's implicit design for the organization's processes, if they will even expose it. However, there is not always a one-to-one correlation between the two. Each process may have more than one enabling technology in use, and each technology is typically employed by multiple processes making shared data available to all of them. The perspectives are different. Falling into the trap of following the technology in a one-to-one mapping effort to create the overall process map will not result in an end-to-end view of the organization's world that can deliver business outcomes.

The processes of the organization are typically enabled by technological services or capabilities. It is especially tempting, given the availability of Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) suites and other off-the-shelf software, to follow the vendor's implicit design for the organization's processes, if they will even expose it. However, there is not always a one-to-one correlation between the two. Each process may have more than one enabling technology in use, and each technology is typically employed by multiple processes making shared data available to all of them. The perspectives are different. Falling into the trap of following the technology in a one-to-one mapping effort to create the overall process map will not result in an end-to-end view of the organization's world that can deliver business outcomes.

Value Chains

Organizations can have multiple lines of business, products, services, markets, and geographies. Trying to mix and match all of these into one consolidated process architecture may be unwise due to the sheer size and complexity of the effort. It may be more feasible to build architectures around a single value chain at a time, each with its own unique value proposition. For example retail banking is quite different from wealth management and what happens on the trading floor. These may all be supported by shared services such as human resource and IT service processes. To be sure you have well-formed value chains, check to see if the processes in each are truly different and serve different stakeholders, measures, and goals. This issue is covered in more depth in Article 2 of this series.

Consistent Naming

True to the proposition of value creation, processes from top to bottom should exhibit a high-quality naming structure. Organizations that have effectively named their processes typically use commonly-understood language (i.e., no jargon), ensure they are quantifiable, and use an action-oriented verb-noun convention. There should be no nouns such as 'the order process'; nouns are for data and things. There should be no gerunds or suffixed verbs such as 'marketing'; that's for departments. There should be no vague, lazy verbs such as 'manage technology'; those are for functions or job descriptions. There should be results or outcomes of value clearly visible in the name such as 'settle claim' and not 'handle claim'. The closing event representing the targeted result of the process should be derived easily from the name such as 'claim settled'. The process value goal or purpose should be apparent in the name.

Simple Categorization based on Process Purpose

A process architecture oriented to an end-to-end view of the business is generally partitioned into three major categories: Core, Guiding, and Enabling Processes.

Core processes deliver goods and services to the customers, clients, or consumers of the value chain or organization. 'Core' should not be perceived as ascribing any higher degree of importance to these processes over any others. Core processes deal with what the organization does to action the customer relationship journey (from birth to death) and the product and service lifecycle (from concept through retirement). This is the actioning of the Mission. It is what the organization gets paid to do. Everything else it does outside of the core must strive to optimize this set of processes.

Guiding processes set direction, plans, constraints, and control over all other processes. They are not the heart of the business but perhaps are the brains. Despite not being Core they can be extremely important.

Enabling processes provide reusable resources that make it possible to do the work of all processes. Again, most organizations go into business to do this type of work, but the Core cannot be effective without the right operational capability in place provided by the Enabling processes.

Many models or organizations use the terms "management processes for guiding" and "support processes for enabling." In my experience, these terms are not clear enough and are often confused with what managers or support departments do or are responsible for, not with the intention of the role they play as part of an end-to-end proposition.

Limited Depth of Structure

In order to remain architectural in perspective, the level of abstraction should remain high, and organizations should not delve too deeply into the details of the process activities. The distinguishing factor should be that the architecture describes 'what we do' and not so much the variations in 'how we do it'. It should also be stable over time unless the business model itself is changed. For example, 'sell' does not say how the organization sells, but sales results can still be measured and sales can be performed in many ways concurrently through varying channels and employing a variety of mechanisms. While not a strict rule, approximately three levels of depth are usually sufficient in an architecture, with perhaps ten processes per sub level for each parent-level process. To sustain the architecture's effectiveness, the end-to-end processes need to focus on the 'what do we do'. This is typically levels 1-3. The 'what' perspective stands the test of time. It also allows organizations to provide a balance between standardization (process and performance) across the organization (including divisions and regions) and the customization necessary to accommodate the 'how we do things' among different groups where appropriate. The customization is often a requirement due to regional and product differences because of varying regulations, norms, systems, and cultures.

Measurable

As mentioned in the value chain section in Article 2, a well-formed architecture-level process should be quantifiable. That's the first test and the first measurement indicator; how many instances of this process are there? If you cannot answer and a good measure is unavailable, then you may have a poor process definition on your hands. Perhaps it should be re-examined or re-scoped. At a minimum, architectural-level processes should always be measurable in terms of their effectiveness and how well each one meets the expected value received in terms of needs met and experiences satisfied. A later article will deal with measurement in depth.

Traceable

In terms of measurement, from the value chain down to lower levels of activities (more detailed) we should ensure that each process contributes to the value expectations of the recipients. With a well-formed, end-to-end architecture this is easier than when using a functional or organizational view of the work. Again, in a later article I will deal with this issue from a measurement point of view in depth.

Aligned

Similar to the goal of traceability, each process in an end-to-end architecture must align with the other processes it interacts with and other management concerns. Outputs of upstream processes act as inputs, guides, or enablers to those downstream. There can be no disconnects and no gaps between the processes. Processes that do send to or receive anything from other processes are orphans and are not allowed into an aligned process architecture because they would not be adding to value chain outcomes. Typically these are just not well designed, and the architecture needs revision to find the right fit for them. The flow of information may not be explicit in the process architecture, but it should be easily derived by looking at the process model from start to end.

What Does A Good End-to-End Process Architecture Look Like?

A process architecture can take many forms and can be easy to do. I have seen a lot of variation, however, and sadly most are not useful for actually operating or managing the business or creating value. Most are too functional, meaning they often line up too conveniently with the organization structure and therefore are not versatile enough to withstand an organizational realignment. That's what you get when you start by asking people in the organization 'what do you do?' as opposed to starting with the external stakeholders and the products and services they deliver, create, and receive.

Another potential pitfall is architectures mostly created by blindly copying a process framework. Frameworks can be extremely useful, but most do not deal well with end-to-end value creation, although they may have a lot of the bits and pieces needed somewhere. They have most of the parts, but the assembly of them into a working value chain is often a problem. I know that all the parts to build a car are in the car-parts catalog, but those parts are not categorized by how you want the car to drive. A useful process architecture must be built from the point of view of the work that must be performed to add value along a chain of activities all the way out to the external world. That means coming inside, starting from the outside, and being agnostic to the organizational groups or the parts catalog. The parts have to be assembled for a purpose.

Useful process architectures have several common characteristics. I will develop this topic in detail next time.

# # #

About our Contributor:

Online Interactive Training Series

In response to a great many requests, Business Rule Solutions now offers at-a-distance learning options. No travel, no backlogs, no hassles. Same great instructors, but with schedules, content and pricing designed to meet the special needs of busy professionals.

How to Define Business Terms in Plain English: A Primer

How to Use DecisionSpeak™ and Question Charts (Q-Charts™)

Decision Tables - A Primer: How to Use TableSpeak™

Tabulation of Lists in RuleSpeak®: A Primer - Using "The Following" Clause

Business Agility Manifesto

Business Rules Manifesto

Business Motivation Model

Decision Vocabulary

[Download]

[Download]

Semantics of Business Vocabulary and Business Rules